Addiction

Why Binge Eating May Not Be a Form of Addiction

A theory of poor validity and clinical utility.

Posted October 1, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- The similarities between binge eating and alcohol and drug abuse have led to the proposal of specific treatments based on addiction model.

- Despite the similarities there are important differences between binge eating and addiction conditions.

- The treatment of binge eating should be based on specific psychological treatments, not on the addiction model.

Some researchers and clinicians have highlighted commonalities between binge eating and alcohol and drug abuse. This observation has led to the introduction of terms such as, "compulsive overeating" and "food addiction," and to propose specific treatments based on the addiction model. However, if binge eating is not an addiction, the treatments based on this conceptualization may not be appropriate.

In this article, I will briefly address two questions: (1) Is it right to view binge eating as an addiction? and (2) What are the implications for the treatment of binge eating?

Is it right to view binge eating as an addiction?

The addiction model sustains that binge eating is produced by the same physiological processes operating in substance use disorders. According to this theory, people who binge eat are biologically vulnerable to specific unhealthy foods, such as sugar and starches, and as a result, become addicted to them, becoming unable to control the amount of their intake. As they have a biological vulnerability to binge eating, they cannot cure their illness and need to learn to accept it and live accordingly.

The theory of binge eating as addiction is supported by both the similarities between binge eating and alcohol and drug abuse and neurobiological findings.

Similarities between binge eating and addiction

The proposers of the addiction model of binge eating highlight the following main similarities between alcohol and drug abuse and binge eating:

- Cravings and urges to engage in the behavior

- Feeling of loss of control over behavior

- Recurrent concerns about the behavior

- Use of the behavior to modulate negative mood and stress

- Denial of the severity of the problem

- Persistence of behavior despite the negative consequences

- Repeated failure to stop the behavior

Neurobiological findings

Some studies have highlighted commonalities in the neurobiological processes of reward between people with recurrent binge-eating episodes and those with substance use disorder. A dopamine increase has been observed both in people who use cocaine and alcohol, following the intake of these substances, and in some people with obesity after food intake. In addition, dopaminergic D2 receptors appear to be decreased both in people with substance use disorder and in some individuals with obesity.

Neurobiological findings have led to the proposition that in healthy individuals the reward system is normally self-regulated in such a way as to allow an appropriate inhibitory control towards the consumption of substances or excessive food. In contrast, in individuals where this system is dysregulated, there would be a tendency to have less control over the intake of substances or food for a reward deficit.

Differences between binge eating and addiction

Despite the similarities, there are important differences between binge eating and addiction that can be summarized in the following points, as described by Professor Christopher Fairburn of Oxford University in his book, Overcoming Binge Eating:

- People with binge eating do not consume classes of foods. If binge eating episodes were a form of addiction, they should be characterized by the desire for and consumption of specific foods. However, this does not usually happen in people with binge eating, where the characteristic aspect of binge eating is the amount of food taken, not the type of food that is eaten.

- People who binge eat have a continuous urge to avoid the binge eating episode. In contrast, one of the greatest difficulties in treating people with substance use disorder is motivating them to try to avoid the use of the substance.

- People who binge often adopt a strict diet to lose weight. Dieting increases the vulnerability to develop binge eating episodes. In contrast, individuals with substance and alcohol use disorder are not vulnerable to substance abuse when they try not to avoid them.

- People with binge eating often show a specific psychopathology. Most people with bulimia nervosa and about half of people with binge-eating disorders report, "the overvaluation of shape and weight" (i.e., judging self-worth almost exclusively in terms of weight, shape, and their control). This psychopathology plays an important role in maintaining the eating disorder and binge eating. In contrast, those with substance use disorder do not show this psychopathology.

- Binge eating seems to derive from the interaction of several biological, social and psychological risk factors and by factors not exclusively associated with eating and food. This suggests that binge-eating episodes are the result of several maintaining mechanisms rather than the consequence of addiction to food.

- The relationship between binge eating and substance use is not specific. The rate of substance and alcohol abuse in people who binge is higher than in the general population, but it is similar to that of individuals with other mental disorders. Similarly, the rate of binge eating episodes is higher in individuals with alcohol and drug abuse, but it is similar to that of individuals with other mental disorders. Even the highest presence of drug abuse in the family members of individuals who binge is not higher than that observed in other mental disorders.

- Those who stop binge eating do not replace food with alcohol abuse. Although eating problems have been observed to precede alcohol abuse (i.e., they arise at an earlier age), data on treatment indicate that those who stop binge eating do not replace the behavior with alcohol abuse.

In addition, as highlighted by Professor Paul Fletcher of the University of Cambridge, the data on the neurobiological findings and reduction of dopaminergic D2 receptors are inconsistent, as are inconsistent the data on individuals with obesity and studies of brain imaging presenting food stimuli to participants with and without eating disorder.

Furthermore, although some foods activate neural pathways common to those of drugs, no evidence has yet shown that there is a neural sensitization to food. In fact, the intense stimulation caused by drugs, which exceeds much that obtained from any food, appears to be the cause of the dysfunction of the natural reward system (including sensitization of the mesolimbic dopamine neurons involved in the process of desire), rather than the mere activation of the desire pathways. This is why addiction to substances becomes so compulsive and persistent, regardless of the pleasure and harm their intake entails. At the same time, this means that a food capable of activating the reward system cannot be automatically classified as an addictive substance.

What are the implications for the treatment of binge eating?

Considering binge eating as an addiction would have inevitable repercussions for its treatment. In fact, the nonpharmacological treatment of food addiction should be based on the approach that Alcoholics Anonymous and other related groups apply to help people with alcohol problems: the so-called "12-step" approach.

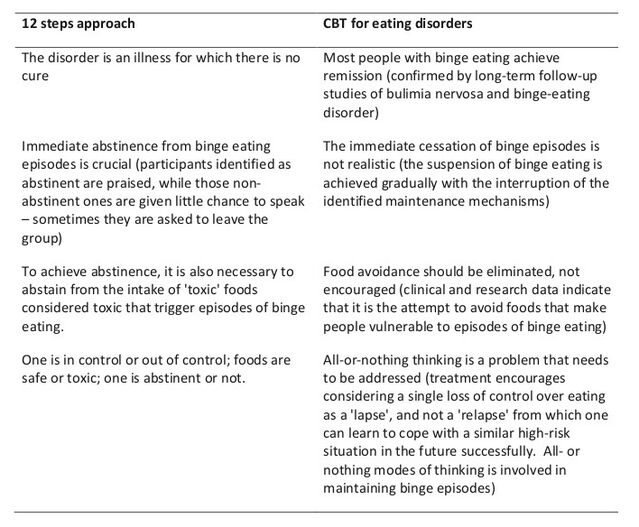

The 12-step approach, as shown in Table 1, differs substantially from the cognitive behavioral therapy of eating disorders (CBT-ED), recommended by the 2017 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. The NICE guidelines reflect substantial new evidence that emerged in the previous decade, focused on the results of controlled clinical trials, and considered the experience of users, family members, researchers, and physicians.

Furthermore, there are no data on the long-term efficacy of binge eating treatments based on the 12-step approach. On the other hand, the findings of CBT-ED are supported by several well-designed clinical studies.

Conclusions

Despite the many similarities between binge eating and substance use disorder, there are fundamental differences between the two conditions with respect to psychopathology, epidemiology, and risk factors.

As Professor Terence Wilson of Rutgers University has stressed, nowadays there is a tendency to use the term of addiction for virtually any form of repetitive behaviors in an imprecise way, with some people said to be sex addicted, social media addicted, TV addicted, a shopaholic, etc. Using the word "addiction" in such a broad and all-encompassing way, most of us could be considered addicted to something.

Of particular concern is the possible adoption of a treatment based on the food addiction model in people with binge eating because, having therapeutic implications that explicitly contradict CBT-ED, the currently recommended treatment for patients with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorders could turn people away from therapies of proven efficacy.

However, it is important to underline that even if we exclude the food addiction model in the genesis and maintenance of binge eating, it is recommended to encourage the implementation of preventive public health interventions, to create an environment that allows most people to adopt a healthy and flexible diet and an active lifestyle.

References

Benton, D. (2010). The plausibility of sugar addiction and its role in obesity and eating disorders. Clinical Nutrition, 29, 288–303.

Fairburn, C.G. (2013). Overcoming binge eating (Second Edition). Guilford, New York.

Wilson, G.T. (2010). Eating disorders, obesity and addiction. European Eating Disorders Review, 18, 341–351.

Ziauddeen, H., & Fletcher, P. C. (2013). Is food addiction a valid and useful concept? Obesity Reviews, 14(1), 19-28