Empathy

Empathy in Nonhumans: Of Peter Kropotkin and Adam Smith

Strange Bedfellows: Kropotkin and Smith's "The Theory of Moral Sentiments"

Posted January 20, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Darwin’s colleague and champion, Thomas Henry Huxley, was not one to mince words. In his 1888 essay The struggle for existence: a programme, Huxley described nature as a bloodbath:

“From the point of view of the moralist, the animal world is on about the same level as the gladiator’s show. The creatures are fairly well treated, and set to fight; whereby the strongest, the swiftest, and the cunningest live to fight another day. The spectator has no need to turn his thumb down, as no quarter is given... .” The same could be said of ancient man, in his “savage” state: “the weakest and the stupidest went to the wall, while the toughest and the shrewdest, those who were best fitted to cope with their circumstances, but not the best in any other way, survived. Life was a continuous free fight, and beyond the limited and temporary relations of the family, the Hobbesian war of each against all was the normal state of existence.”

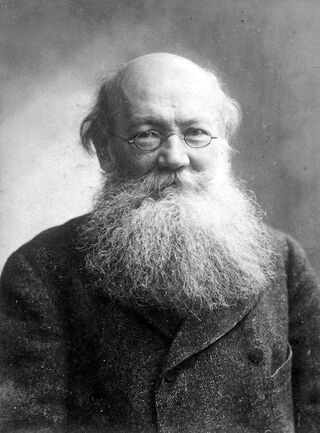

Most British scientists of the day agreed with him. But Russian evolutionary biologist and anarchist Peter Kropotkin, who had spent five years trekking across Siberia, studying the natural history of animals, didn’t. Kropotkin was a Darwinist who was certain that natural selection could, and did, favor what he called mutual aid in nonhumans: what today we might call altruism and cooperation. In time, Kropotkin proposed the “the law of mutual aid” in which mutual aid was of “the greatest importance for the maintenance of life, the preservation of each species and its further evolution.”

Contrast Huxley’s depiction of the natural world with the one painted by Kropotkin in his classic 1902 book, Mutual Aid:

"Wherever I saw animal life in abundance… on the lakes where scores of species and millions of individuals came together to rear their progeny; in the colonies of rodents; in the migrations of birds which took place at that time on a truly American scale along the Ussuri; and especially in a migration of fallow-deer which I witnessed on the Amúr, and during which scores of thousands of these intelligent animals came together from an immense territory… in all these scenes of animal life which passed before my eyes, I saw mutual aid and mutual support carried on to an extent which made me suspect in it a feature of the greatest importance for the maintenance of life, the preservation of each species, and its further evolution.”

Kropotkin was not satisfied with an evolutionary theory for mutual aid: he also needed to understand mutual aid from a proximate perspective: in real-time, what caused animals to dispense help to one another? His search led to a most unexpected source: Scottish economist Adam Smith.

Kropotkin knew well Smith’s 1776 book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Kropotkin, the political anarchist, was an economic socialist who had nothing good to say about what was already considered the bible of capitalism. But, Smith’s other book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), would provide Kropotkin what he needed.

Kropotkin thought that The Theory of Moral Sentiments was “far superior to the work of his [Smith’s] old age upon political economy.” In that book, Smith argued that empathy was the key to human goodness. Smith’s argument was that we want to do is to minimize our pain and discomfort. Because we humans can put ourselves in the position of the other and assume they feel what we would feel in their situation, we help others who are in discomfort or pain, as that action reduces the vicarious discomfort or pain we experience as a result of our empathetic nature. “How selfish soever man may be supposed there are evidently some principles in his nature,” Smith wrote, “which interest him in the fortune of others…of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion which we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.”

After reading The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Kropotkin saw empathy as the key to a proximate understanding of mutual aid in animals. Smith’s theories on mutual aid and empathy in humans were spot on, Kropotkin thought, they just stopped short when they need not have. In an 1890 article entitled Anarchist Morality, Kropotkin wrote that “Adam Smith's only mistake was not to have understood that this same feeling of sympathy in its habitual stage exists among animals as well as among men.”

Empathy, Kropotkin believed, was the proximate key to animal as well as human mutual aid.

References

Huxley, T.H. (1888). The struggle for existence: a programme. Nineteenth Century 23, 161-180.

Kropotkin, P. (1902). Mutual Aid. (London: William Heinemann).

Kropotkin P. 1890. Anarchist morality. "Freedom Office" 127 Ossulton St. NW.

Smith A. 1759. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. London: Henry Bohn.