Placebo

Prestige, Power, and Placebos

Unpacking the healing effects of cultural expectations.

Posted March 22, 2017

In a recent post on the Trump Effect, I described a short list of cognitive biases that possess the power to direct our attention, prescribe our beliefs and preferences, and guide most of what we do and think. Like our stomach's evolved cravings for fat and sugar, the human mind is uniquely hungry for a short list of social cues. As we will see, cultural information is not just attention-grabbing. When the context is right, it can also possess remarkable healing power.

Let's find out how this works, and how to use this power for the greater good.

Trumped by our social minds

The Trump Effect does not describe a conspiracy of malefic agents who manipulate our opinions. Rather, it explains why we are so prone to what I call the “misattribution of agency”: that is, the tendency to treat complex, abstract processes like “society,” “the media,” “Republicans,” or "the brain" as single entities with a mind and intentions of their own (e.g., “society doesn’t want you to get rich,” “the media is lying to you,” or “my brain won't let me do this”).

The recipe for the Trump Effect is short and simple: 1) we outsource most of our thinking to people we automatically associate with our in-group; 2) we further reinforce our beliefs by contrasting them to those of our out-group, which gives us the illusion that we have made a moral choice, and 3) we intuitively find the most high-quality, high-fidelity information from within our in-group by being uniquely hungry for prestigious models.

These cognitive biases are well documented in decision-making science. Ideas that spring to mind effortlessly, for example, tend to reflect whatever we picked up from prior learning and frequent exposure, but not critical thinking. Psychologists call this the ‘availability heuristics’ and explain that it often leads us into intuitive errors. Let’s look at how this works.

The power of schemas

Assuming they were raised in the West, ask anyone over the age of 10 the following question:

“How many of each kind of animal did Moses take on the ark?”

Most people will answer ‘2’, or if they think a little harder and want to show how clever they are, they will answer ‘1’ and explain that a pair of animals represents a single kind.

Think about that for a minute.

The answer, of course, is none. In the biblical story, it was Noah, and not Moses, who brought the animals on the ark!

The ‘One-item Moses Illusion Task’ is a famous measure of analytical thinking. Most people—including students and graduates of elite universities—fail to see the obvious answer. Why is that, and what, you might ask, does it have to do with placebo effects and healing power?

An often overlooked dimension of the availability heuristics and intuitive errors is that they tend to be primed by culture—that is, by ideas that seem intuitive because they are culturally widespread within specific groups. In the Moses Illusion task, most people raised in the West are so familiar with biblical stories that they will invest no mental effort whatsoever in examining the context of the riddle.

The words ‘Moses’ and ‘Noah’ share a phonetic structure, but more importantly, they are stored in memory within a similar cultural schema. People raised in countries in which biblical stories are distant and exotic tend to do much better on the Moses task. If they have to think “wait a minute… what was that Ark-thingy again?” and effortfully remember Noah, the illusion will seem obvious to them.

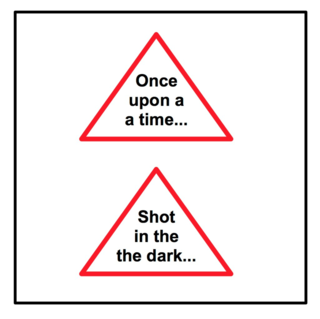

Let’s spend another minute learning about schemas. Can you remember the words that appeared in the red triangles a few paragraphs above? If you think they said “Once upon a time,” and “a shot in the dark,” think again!

Still can’t see what is really written in the triangles? Try covering the words with your finger and reading them one by one.

If, like most of us, you experienced great difficulty in seeing the actual words in the triangle, you were trumped by a maladaptive schema. A schema describes a pattern of thought or behavior that packages chunks of previously learned information and the relationships among them.

With my colleagues Laurence Kirmayer and Maxwell Ramstead, we understand most schemas as emerging through culturally patterned practice. Drawing on current computational neuroscience, we now understand the role of the brain as that of a prediction-machine: Prior learning prompts us to see the world as we already expect it to be, but not as it really is. Once a cultural schema is already in place, in other words, and if the cues around us look right enough, we will be blind to context and automatically process information as we expect it to appear.

How do misattributions of agency, in-group, and prestige biases come into play, and what does this have to do with healing?

The power of prestige

Consider the so-called Angelina Jolie effect. In 2013, when the actress got tested for the BRCA1 gene (associated with an increased risk for breast and ovarian cancers), she chose to undergo a preventive double mastectomy and reported on her choice in a New York Times Op-Ed. Following her publicized testimonial, the British Journal of Psychiatry documented an exponential spike in breast-cancer screening and inquiries about mastectomies.

Why did it seem ‘obvious’ and intuitive for so many young women to undergo screening after Angelina Jolie did it, but not beforehand? Surely, ideas about breast cancer and screening opportunities must have already been culturally widespread as result of public health campaigns.

Once again, we must appreciate the power and limits of intuitions. Presenting people with empirical facts about what is good or bad for them is rarely enough to inspire a behavior change. When prestigious people from our own cultural groups adopt a new idea, trend, or practice, however, the ‘choice’ to emulate them often feels ‘obvious’. This is what cognitive anthropologist Joe Henrich calls Credibility Enhancing Displays. For a behavior to be desirable, it needs to be displayed by prestigious agents—by people we can look up to as reliable sources of high-quality, high-fidelity information. Marketing experts have been aware of the human craving for prestige for a long time: This is why they sell brands through celebrity endorsement. Celebrity endorsement, for better or for worse, is now increasingly appreciated as an important strategy in public health.

The cultural foundations of placebo effects

We have now unpacked enough cultural psychology to talk about placebos.

Placebos are usually understood as inert pills with no medical properties. They typically work through the power of belief alone. Because people expect them to be medicine, the power of their expectations does all the healing work. But placebos need not entail a pill. Sham surgeries with nothing more than an anesthesia procedure and a superficial cut and stitch ritual have been known to be very effective in the treatment of chronic pain!

The efficacy of placebo effects, for example, tends to increase when cultural ingredients are well curated—or in other words, when pre-existing cultural schemas are met. Placebos that seem expensive work better than those that look cheap; technologically elaborate placebos (like sham surgeries) work better than pills, and healing responses are highest when the settings look ‘clinical’, or when experimenters ‘really look like doctors.’

Some recipes for placebo effects may be more universal than cultural: blue and purple pills typically produce soothing effects, while red pills work best as stimulants.

The power of culture in placebo effects, however, is still underappreciated. For Italian men, blue pills are not very successful at inducing calming effects. Why? Because they tend to associate the color blue with their national soccer team, and the high arousal they feel during soccer games.

Recall the cultural nature of the availability heuristics: For intuitions to be really strong, people must expect that enough people from their group also expect the same thing.

The Harvard psychologist Irving Kirsch is among the few scientists who understands the power of cultural expectations in placebo effects. Kirsh elicited a broad controversy by pointing out that while SSRI medications used for the treatment of depressions only outperformed placebos in clinical trials by a very small margin, both medications and placebos appeared to have become more 'effective' over time. For Kirsh, this increase in the healing power of dubious drugs with well-documented adverse effects was primarily caused by two shifts in cultural beliefs: 1) increased collective belief in the existence of depression as a brain disease, and 2) belief in the fact that many people who suffer from depression and take SSRIs have gotten better.

We have now presented enough cultural and cognitive ingredients to fully unpack the healing power of placebos. Like celebrities, certain kinds of knowledge and technologies (the more ‘medical’ the better) possess enough prestige to guide our deepest expectations about what is true and what works.

The symbolic power of neuroscience

Working from these hypotheses, my colleagues in the Raz Lab in Cognitive Neuroscience at McGill have found that explanations and technologies involving neuroscience possess immense deceptive power—and healing power!

In a series of clever experiments on what they term “neuroenchantment,” Amir Raz and his researchers found that even students with advanced standing in psychology and neuroscience could be tricked into thinking that a crudely built sham ‘brain scanner’ could produce improbable diagnostic and physiological effects. In a first round of experiments using fake brain technology built from a hair-dresser’s chair and discarded odds, my colleagues were able to get participants to believe that the machine was reading their thoughts.

In a subsequent design involving a more realistic-looking (but equally fake) brain imaging machine, participants similarly believed that the technology could read, but also influence their thoughts, with many reporting on an “unknown force” directing their thinking toward specific numbers.

The experimental psychologist Jay Olson, who, like Amir Raz, first trained as a magician, has now perfected the sham scanner method to get participants to change their attitudes.

In a soon-to-be-published study led by Olson, 60 participants wore a sham EEG cap that they were told would detect discrepancies between their reported attitudes and their unconscious, 'true' attitudes. After completing several questionnaires, participants were told that the scanner detected discrepancies in three questions related to charity. When asked why this discrepancy might have occurred, 80% of participants confabulated to confirm the scanner’s 'true' diagnosis. They subsequently changed their charity attitudes by donating money to a confederate who had been planted on campus to test their behavior.

Pessimistic conclusions?

At first glance, experimental research on neuroenchantment seems to carry pessimistic insights. Humans, as decades of research in decision-making science have shown, are usually blind to context, prone to intuitive errors, and extraordinarily influenceable by culture and prestige.

But the immense physiological power of expectations—and of the encultured mind itself—is often understated. Studying the placebo power of prestigious people, forms of knowledge and technology is fascinating in its own right. This research agenda gives us a fascinating window into the neural and ecological processes that underpin mind-body regulation. Even more overlooked, however, is the immense healing power of cultural expectations.

The healing power of accessory-assisted suggestion.

Experiments conducted in our lab have clearly shown that when people’s cultural schemas are carefully curated and met, the subsequent shut-down of inefficient ‘hard thinking’ cognitive resources can greatly facilitate physiological responses that normally lie outside of conscious control.

A total absence of critical thinking, in other words, can also produce wonderful effects on bodily functions that are typically regulated by the autonomic-nervous-system, but not by the rational mind. The key, then, lies in learning how to use these effects for the greater good.

In pilot experiments with volunteer subjects, my colleagues and I have found that the symbolic power of mock brain technology and clinical settings could be very effective in the treatment of migraines and involuntary behaviors like nervous tics. The cultural expectations and cognitive biases that direct our thoughts and feelings, in other words, can also be harnessed to induce healing.

Our tendency to treat complex processes and objects as minded entities, for example, can be treated as a wonderful resource to work with. Thus, telling an anxious child that “the machine really wants [her] to feel good” can produce instant effects. In a cultural context where children ascribe inordinate agency to “their brain,” a simple suggestion like “the machine tells me that your brain is doing the right thing, you're going to be fine!” from a medical-looking experimenter can suffice to produce strong healing responses.

Our pilot experiments strongly suggest that the battery of healing effects that can be achieved under hypnosis can be replicated with greater ease under accessory-assisted suggestion conditions.

The reasons for this are simple. A hypnotic induction procedure is typically demanding for both hypnotist and client. It can take a long time and many sessions for a client to learn to relax and suppress their doubts, trust the operator, and let their unconscious mind take over.

Conversely, by using powerful symbols, accessories, and curated contexts as suggestions, we are able to bypass costly induction methods and produce faster, stronger healing responses.

Sure sell or tough sell? Practical and ethical considerations.

Promoting the accessory-assisted suggestion method as evidence-based treatment might be a difficult sell. For one, culturally widespread knowledge that the method is a ‘placebo’ might dampen or nullify the effect.

Our preliminary results, however, suggest otherwise. When a few sessions in a sham-scanner give a client the hope, then expectation, then demonstrated results that their symptoms can reduce or go away, they can subsequently come to expect that 'their brain' has learned to fix a problem. Once their attention is retrained and new coping skills are ingrained, the hindsight knowledge that treatment was initiated under hypnotic suggestion is unlikely to reverse new coping habits. In a very real sense, new automatic schemas will have been put in place, and the clients’ brains will have been rewired.

A call to the scientific community

To further verify this hypothesis, we hope that our accessory-assisted suggestion paradigm will be adopted by more researchers who can test its validity and efficacy under different longitudinal conditions.

We also accept that many people are likely to object to the use of suggestion on moral grounds. The morality of suggestion is a very difficult ethical question that raises further dilemmas on the nature and limits of truth and rationality.

On the one hand, cognitive science has shown that cultivating an analytical stance is of crucial importance in reducing intuitive errors, addressing our implicit biases, being more attentive to context, and even reducing inter-group conflict. On the other hand, meditation, hypnosis, and placebo science have shown that learning to tap into our unconscious resources can have immense healing effects.

It is important to note that suggestion-assisted healing cannot, and should not be used for clearly defined and well-understood conditions that demand medical attention and respond well to pharmacological treatment. Culturally assisted, accessory-assisted suggestion will not mend broken bones, prevent malaria, or offer a substitute for insulin, chemotherapy, or even psychotherapy.

For the many syndromes and chronic conditions that elude current medical understanding and treatment, however, we are confident that our paradigm can be used to supplement other therapeutic tools and help many people regain a better quality of life.

It may very well be, then, that the immense healing potential of culturally enhanced suggestion will become the new no-brainer in treatment choice for many hard-to-treat, non-life-threatening conditions.

I conclude by quoting Article 37 of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects on the topic of unproven interventions in clinical practice:

In the treatment of an individual patient, where proven interventions do not exist or other known interventions have been ineffective, the physician, after seeking expert advice, with informed consent from the patient or a legally authorised representative, may use an unproven intervention if in the physician's judgement it offers hope of saving life, re-establishing health or alleviating suffering. This intervention should subsequently be made the object of research, designed to evaluate its safety and efficacy. In all cases, new information must be recorded and, where appropriate, made publicly available.

In this short, 30-second survey, please let us know what you think about the ethics of this novel approach to treatment. Thank you!