Relationships

Intergenerational Healing Journey With My Korean Mother

Personal Perspective: How courageous conversations reconcile relationships.

Posted April 15, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Right after my father’s death from a heart attack in winter 2009, my mother, at age 65, was diagnosed with dermatomyositis, a rare inflammatory autoimmune condition accompanied by muscle weakness and distinctive skin rashes. A few times, she was hospitalized in an intensive care unit. With her medical condition and the sudden death of my father, she soon became depressed, resentful, and isolated. When I told my mother I was engaged to a woman, she called my marriage a blasphemy based on her religious conviction and suddenly stopped responding to all of my calls and postcards.

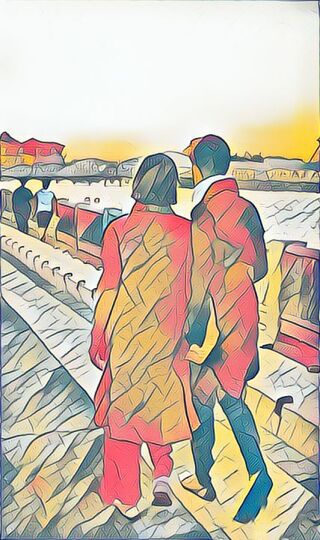

Three years later, I had an opportunity to present at a professional conference in Thailand. Being surrounded by Asian faces, I realized how much I missed my mother. Despite my fear of her rejection, I gingerly asked her if she would see me if I flew to South Korea after my presentation. Unexpectedly, she accepted my proposal to meet, even travel together to Jeju, a beautiful island south of the South Korean peninsula. At first, I was surprised by her openness. Then, I was even more astounded by what she started revealing to me—a long, long list of family secrets, one laid out after the other.

During our Jeju trip, listening to the story about my maternal grandmother opened a window into a past that I could never have imagined: My grandmother’s life swung wildly between poverty and privilege, Japanese colonization and the Korean War, an impressive legal victory that stunningly ended in business bankruptcy, depression, and isolation. My mother’s revelations helped me understand my grandmother’s baffling silence.

My mother went on to share stories about skeletons in her own closet. She spoke of fleeing her village overnight and leaving everything behind, including family members and friends and every possession—from jewelry to photos to her favorite shoes. Her family was forced to leave behind the gravesite of her father, who died during the Korean War.

Along with those things, my mother surrendered her dreams of studying literature and writing poems and novels. Instead, she became a nurse to support her own children and her mother. Rather than living a life of arts, she faced gender discrimination and sexism as a community leader in a conservative Korean society. Both my grandmother and mother survived through their tumultuous lives the only way they knew how—by enduring pain and swallowing their sorrows with silence.

In our courageous conversations, my mother and I rediscovered love, forgiveness, and liberation through the process of unpacking troubling yet formative personal stories. I started to connect dots, making sense of my restlessness and rootlessness.

Then, we decided to write a book, one which my mother hopes “comforts the mourners, binds up the brokenhearted, and encourages those in despair.” For over a month’s time, a series of notification sounds from my phone woke me up each morning. They were from my mother, who was dedicated to making progress on our writing project. She sent photos of her notes—handwritten in her beautiful script, nicely numbered and chronologically organized. I paused to savor her sentences, so rich with the newfound energy of her unexpected transformation.

While writing our book, I once asked her what would have allowed her to make better decisions or start her healing process earlier in life. “Having just one person to consult with,” she said. My mother never talked with my grandmother about hardships in her life. About this, my mother explained, “It’s not like we didn’t love each other. We just didn’t know how to talk vulnerably; we didn’t know how to listen to a painful story to support each other. We didn’t know how to encourage or comfort each other.”

Then, she looked me in the eye and said words I will never forget, “Now, I have that one person in my life. It’s you, daughter. I decided to tell you about my stories, and now I have shared even more than I expected. I told you everything. I don’t feel sad anymore. I even laugh at myself and my nonsensical decisions. Now I have that one person.”

A Harvard University study published in 2015 reveals that children who do well despite serious hardship have had at least one stable and committed relationship with a supportive adult. Such a bond buffers a child from developmental disruption and helps them develop resilience to respond to adversity and bounce back to thrive. This is also true for my 74-year-old mother, who has gone through numerous traumatic events in her life. Through a stable and committed relationship with a supportive adult, her daughter, she reconnected with her younger self, restored some childlike qualities and resilience, and responded to her experiences with new perspectives, self-compassion, and hope.

As a professor at San Jose State University teaching various counseling theories and providing support for many individuals and families suffering from trauma, the process of unpacked halting stories with my own mother deepened my understanding of how unspoken shame that began from generation to generation, forming a chain into the family’s unexamined past, could mummify individuals. I've met many Asian women who think our silence protects us from shame, guilt, and judgment. We think keeping quiet keeps us safe. However, the truth was the opposite for my family; those things became invisible walls keeping us apart from each other and from others in the world. We kept our stoic faces and defense mechanisms, and we felt lost inside. I forgot how to genuinely connect with myself and others until I began writing a book together with my mother. Together, we transformed our trauma into a source of love and healing.