Mindfulness

7 Tips for Using Mindfulness in Talking Therapies

A guide for using mindfulness techniques in client-therapist settings.

Posted December 5, 2019 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Based on my own and others’ research and practice of mindfulness, the following seven tips are intended to assist psychotherapists, counselors, mental health practitioners, and other talking therapists wishing to use mindfulness techniques in client-therapist settings:

1. Foster an Experiential Understanding of Mindfulness. My own research indicates that clients place significant importance on the extent to which the therapist embodies mindfulness principles. When the therapist has cultivated a good level of mindful awareness in themselves, it helps clients to relax and connect with their own capacity for transformation and healing. In other words, if a therapist is going to guide others to practice mindfulness, it’s important they do so from an experiential standpoint. Furthermore, talking therapists can be at risk for compassion fatigue, which is a form of secondary stress caused by working with clients who have distressing problems or who have experienced trauma. Therapist mindfulness practice has been shown to exert a protective influence over compassion fatigue and can therefore help to improve the therapeutic experience for client and therapist alike.

2. Practice Mindful Listening: As with all talking therapies, the therapist’s ability to listen deeply to clients is important for therapeutic connection. But in the case of mindfulness therapy, in particular, there are additional dimensions to this listening process. When correctly practiced, mindful listening involves the therapist listening to the entirety of the person in front of them. It involves listening just as much to what a person is saying as it does to what they are not saying. It not only requires listening carefully to (for example) the client’s feelings, beliefs, assumptions, and voice tone, but also to the extent that the client is present in the ‘here and now.’ Of equal importance, mindful listening requires the therapist to listen carefully to their own thoughts, concepts, and perceptions that are triggered by the person in front of them and that could interfere with the therapist’s ability to be unconditionally accepting.

3. Encourage Life Integration. Although it’s likely to be beneficial for the client and therapist to meet regularly, equal emphasis should be placed on equipping clients to introduce mindfulness into all aspects of their lives. In this respect, it’s often useful to guide clients to establish a routine of mindfulness practice, which in addition to being tailored to the client’s individual needs, should be both dynamic and flexible. The purpose of this is to reduce the likelihood of clients becoming dependent on formal seated meditation sessions or seeing mindfulness as a means of escaping from their problems.

4. Use Mindfulness Anchors. Integral to effective mindfulness therapy is helping clients understand and apply the concept of mindfulness anchors. A good example of a mindfulness anchor is observing the breath. Full-awareness of the in-breath and out-breath helps clients ‘tie their mind’ to the present moment and subdue thought rumination. If a client has low levels of concentration, teaching them to count their breath in and out can be helpful. However, when using breath awareness as a mindfulness anchor, it’s important to discourage clients from forcing their breathing. In other words, the breath should be allowed to follow its natural course and to calm and deepen of its own accord.

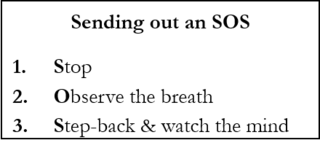

5. Employ Mindfulness Reminders. An example of a mindfulness reminder is an hour chime (e.g., from a wrist-watch, wall clock, or mobile phone), which, upon sounding, can be used as a trigger by the client to gently return their awareness to the present moment and the natural flow of their in-breath and out-breath. Some clients seem to prefer a less sensory reminder such as a simple acronym. For example, I sometimes teach the following three-step technique that involves sending out an SOS at the point distraction or intrusive thoughts arise: 1. Stop, 2. Observe the breath, 3. Step-back and watch the mind.

6. Highlight the Importance of Meditative Posture. While the focus should be directed towards maintaining mindful awareness during everyday activities, daily seated-meditation sessions are also important. A suitable body posture during meditation helps give rise to a suitable mental posture, whereby the mind should be relaxed and supple but also alert. An important aspect of body posture during meditation is stability, which can be achieved whether sitting on a chair or a meditation cushion. The advice I often give when explaining the appropriate posture for seated meditation is to ‘sit like a mountain.’ A mountain has a definite presence, it is upright and stable yet at the same time, it is without tension and doesn’t need to strain to maintain its posture. Even when bombarded by stormy weather, a mountain is solid, relaxed, and deeply rooted in the earth.

7. Use Psycho-Education. In most talking therapies, a degree of psycho-education regarding how the therapy works and possible hurdles to recovery is generally a good idea. Mindfulness therapy is no exception to this, and clients generally welcome advance notice of the difficulties they might encounter as their mindfulness training progresses. One such difficulty, particularly in the beginning stages, is a feeling by clients that their mind is becoming more unruly than before. However, rather than a reduction in mindfulness levels, this impression invariably arises due to a greater awareness by clients of their mind’s inclination towards distraction. Furthermore, in the context of mindfulness therapy, psycho-education should be regarded as a two-way process, whereby through discussing different dimensions of the client’s problems and mindfulness practice, a shared wisdom arises that both the client and therapist can benefit from.

References

McCown, D., Reibel, D. K., & Micozzi, M. S. (2010). Teaching mindfulness: A practical guide for clinicians and educators. New York: Springer.

Campbell, J. C., & Christopher, J. C. (2012). Mindfulness to create effective Counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counselling, 34, 213-226.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon W., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Practical tips for using mindfulness in general practice. British Journal of General Practice, 64, 368-369.

Shonin, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2015). Practical recommendations for teaching mindfulness effectively. Mindfulness, 6, 952-955.

Van Gordon, W., & Shonin, E. (2018). Mindfulness: The art of being human. Mindfulness, 9, 664-666.

Van Gordon, W., & Shonin, E. (2019). Second-Generation Mindfulness-Based Interventions: Toward More Authentic Mindfulness Practice and Teaching. Mindfulness, Advance Online Publication, DOI: 10.1007/s12671-019-01252-1.