Neuroscience

A Primer on Consciousness and the Brain

Unpacking theories about the neural correlates of consciousness.

Posted March 22, 2019

For those of you who follow this blog, here’s a primer that covers in just ten pages many of the novel ideas that have been presented over the years in this blog, Consciousness and the Brain.

Some of the ideas in the primer were presented at a recent, wonderful conference held at the University of California, Davis. At the conference (Northern California Consciousness Conference) scientists from different backgrounds discussed theories of consciousness and debated about the neural correlates of consciousness (click here for more information).

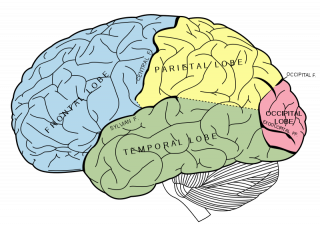

For example, some theorists proposed that consciousness is primarily a function of the frontal cortex, while other theorists proposed that consciousness is primarily a function of posterior brain areas or of subcortical areas. It seems that the jury is still out regarding the neural correlates of consciousness (click here for more information regarding this debate).

One thing that seems clear is that consciousness seems to be associated with only a subset of brain function. It is important to appreciate that consciousness of some kind persists with the non-participation (e.g., because of lesions) of several brain regions, including the cerebellum, amygdala, basal ganglia, mammillary bodies, insula, and hippocampus. In addition, investigations of ‘split-brain’ patients reveal that consciousness survives following the non-participation of the non-dominant (usually right) cerebral cortex or of the commissures (e.g., the corpus callosum) linking the two cortices.

Some researchers have proposed that, in order to further isolate the neural correlates of consciousness, one should focus on the olfactory system, for several reasons. One reason is that olfaction involves a brain area that consists of paleocortex (which contains only half of the number of layers of neocortex). Second, olfaction also involves only one brain region—the frontal cortex. In contrast, vision and audition involve mostly neocortex and often involve large-scale interactions between frontal cortex and parietal cortices, which makes things more complicated. Third, olfaction can reveal much about the contribution of thalamic nuclei in the generation of consciousness: Unlike for the other senses, afferents from the olfactory sensory system bypass the first-order, “relay” thalamus and directly target the cortex ipsilaterally. This minimizes spread of circuitry, permitting one to draw conclusions about the necessity of first-order thalamic relays in (at least) this form of sensory consciousness.

There are also phenomenological properties that render this system a fruitful network in which to investigate the neural correlates of consciousness. Unlike what occurs with other modalities, olfaction regularly yields no subjective experience of any kind when the system is under-stimulated. This happens when odorants are in low concentration or during sensory habituation (e.g., as when one works in a bakery and no longer can smell the bread). The “experiential nothingness,” which is unlike the blackness experienced when the eyes are closed, is associated with olfaction yields no conscious contents of any kind to such an extent that, absent memory, one in such a circumstance would not know that one even possessed an olfactory system. For these reasons, olfaction provides an excellent portal for understanding the neural correlates of consciousness.

References