Philosophy

The Matrix Problem: Can We Trust Our Minds and Our Senses?

What a butterfly dream, simulations, and neuroscience teach us about perception.

Posted March 29, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- After a dream, an ancient Chinese philosopher asked if he is not now a butterfly dreaming of being a person.

- Such radical scepticism is still being fervently discussed, gaining popularity through 'The Matrix' movie.

- Modern neuroscience shows that perception is not a perfect representation of external reality.

- People need to be aware of limitations in their perception but simultaneously embrace what it provides.

From a butterfly to radical skepticism

During the warm summer months in ancient China, the philosopher Zhuang Zhou (also known as Zhuangzi or Chuang-Tzu) dreamt he was a carefree butterfly, fluttering about as he pleased. But then he suddenly woke up and realized that he was in the solid and unmistakable form of Zhuang Zhou. But was it really the old philosopher who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or was he a butterfly that was now dreaming about being a Chinese philosopher?

This brief experience caused a huge stir for millennia, with many different interpretations put forward (Chen, 2020), and it is still being discussed by philosophers almost 2,500 years later (Han, 2010). Many have seen it as the beginning of radical skepticism, the philosophical view that knowing anything for sure is impossible (Pritchard, 2016), which has had a profound impact on science in general, but especially on psychology and neuroscience. Radical skepticism raises doubts about whether we can trust our minds or our senses.

The Matrix problem

The 1999 movie The Matrix portrayed a dystopian world where humans live in a simulation, and every sensory experience is fed directly into their brains. How would we know if we, in fact, lived in a Matrix-like simulation? Such questions have recently been rekindled by serious philosophers like Nick Bostrom (2003). The idea itself is not new and has been described as the brain in a vat hypothesis by earlier philosophers (Pritchard, 2023).

Even if we accept that the world around us is real, how can we know that the way we perceive it is accurate? This taps into another debate that started in antiquity.

Pomegranates and illusions

Not long after Zhuang Zhou wrote about his butterfly dream, ancient Athens saw the rise of a new school of philosophy called stoicism. The popularity of the stoics created a conflict with the established Academy, arguably the first proper school of philosophy (Seitkasimova, 2019), founded by Plato. The two schools engaged in a philosophical battle that lasted for several hundred years (Striker, 2011). At the heart of their debate was the question of whether we can trust our senses or not. The stoics insisted that we perceive real things exactly as they are—just like a seal stamp makes a precise impression on a blob of wax—which the followers of the Academy rejected. What followed was a centuries-long discussion with examples and counterexamples.

Diogenes Laërtius (ca. 230/2018) described an anecdote where King Ptolemy Philopator of Egypt invited the stoic philosopher Sphaerus to a banquet and had wax pomegranates placed on the table. When Sphaerus reached out for one, the king triumphantly declared that the philosopher assented to a false perception. The debate at this point was very technical and revolved around “assenting” to perceptions rather than the perceptions themselves. Sphaerus retorted that he did not assent to the fact that they were pomegranates but merely to the fact that it was probable that they were pomegranates. So, the debate continued.

At first sight, this may seem like senseless hair-splitting by ancient philosophers, but these debates have raised profound questions: Can we trust our minds and our senses? We have moved on from wax pomegranates, but the question of the accuracy of sensation and perception is still a key area of study not just in philosophy, but also in modern psychology and neuroscience.

Psychology and neuroscience

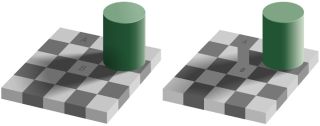

Sensation and perception have been part of psychological investigations from the very inception of the field. These scientific approaches have shown us that what we experience is merely an interpretation of reality constructed by our brains. It is this interpretation that helps us make sense of the world and navigate complex environments (Pang, 2023). However, the fact that perception differs from sensation also means that it can be manipulated and misled, for example, through illusions and magic tricks (Svalebjørg et al., 2020). Psychoactive substances can also drastically alter our perception (Aday et al., 2021).

Can we trust our senses?

There are clear differences and gaps between reality, what our senses pick up, and how we perceive these sensory inputs (Pang, 2023). Because of that, we cannot definitively rule out that our experiences do not correspond to an external reality, which gives a foothold to radical skepticism—from butterfly dreams to brains in a vat to computer simulations.

Does that mean that we cannot trust our senses or our experiences? I think the answer is both yes and no. Reality is in many ways richer (there are so many things we are not aware of because they are outside our range of perception) but in some ways also poorer (no pink or magenta, see “Why pink doesn’t exist: Lessons in perception and reality”) than the way we experience it. Only when we accept our perceptual limitations can we start to venture beyond them.

At the same time, rejecting them outright is not just impractical but also ignores that while our perception may not be perfect, our brains still exceed the most powerful computers at constructing the best representation of what is important to us about the reality around us (Ernst, 2006; Ernst & Banks, 2002). We should use our rational abilities to try to uncover deeper truths, but that must not take away from using our perceptions to navigate the world and enjoy the deep and meaningful experiences they provide.

References

Aday, J. S., Wood, J. R., Bloesch, E. K., & Davoli, C. C. (2021). Psychedelic drugs and perception: A narrative review of the first era of research. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 32(5), 559-571. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2020-0094

Bostrom, N. (2003). Are we living in a computer simulation?. The philosophical quarterly, 53(211), 243-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9213.00309

Chen, J. (2020). Zhuangzi and his butterfly dream: The etymology of meng. In J. Golley, L. Jaivin, B. Hillman, & S. Strange (Eds.) The China Year Books: China Dreams. ANU Press. http://doi.org/10.22459/CSY.2020

Diogenes Laërtius. (ca. 230/2018). The lives and opinions of eminent philosophers. Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/57342/57342-h/57342-h.htm

Ernst, M. O. (2006). A Bayesian View on Multimodal Cue Integration. In G. Knoblich, I. M. Thornton, M. Grosjean, & M. Shiffrar (Eds.), Human body perception from the inside out: Advances in visual cognition (pp. 105–131). Oxford University Press.

Ernst, M. O., & Banks, M. S. (2002). Humans integrate visual and haptic information in a statistically optimal fashion. Nature, 415(6870), 429-433. https://doi.org/10.1038/415429a

Han, X. (2010). Interpreting the butterfly dream. Asian Philosophy, 19(2009), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09552360802673781

Pang, D. K. F. (2023, May 29). Why pink doesn’t exist: Lessons in perception and reality. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/consciousness-and-beyond/202305/perception-reality-and-why-pink-doesnt-exist

Pritchard, D. (2016). Epistemology. Palgrave Macmillan.

Pritchard, D. (2023). What is this thing called knowledge? [5th ed.]. London: Routledge.

Seitkasimova, Z. A. (2019). May Plato’s Academy be considered as the first academic institution?. Open Journal for Studies in History, 2(2), 35-42. https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsh.0202.02035s

Striker, G. (2011). Ancient Scepticism. In S. Hetherington (Ed.) Epistemology: The key thinkers (pp.72-89). Bloomsbury Academic.

Svalebjørg, M., Øhrn, H., & Ekroll, V. (2020). The illusion of absence in magic tricks. i-Perception, 11(3), 2041669520928383. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2041669520928383