Anxiety

Is the Way You Deal With Anxiety as Safe as You Think It Is?

Overdose deaths involving benzos increased from 1,135 in 1999 to 11,537 in 2017.

Posted October 15, 2019

You trust your doctor. Your doctor prescribed Xanax. It must be alright to take it, right?

Maybe. Maybe not.

“Generally speaking, primary care physicians have not received the training that they need to prescribe medications that have such high risk for addiction or overdose," said Dr. Joanna Starrels, professor at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Though psychiatrists prescribed benzodiazepines no more often, during the period from 2003 through 2015, prescriptions by primary care physicians more than doubled, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

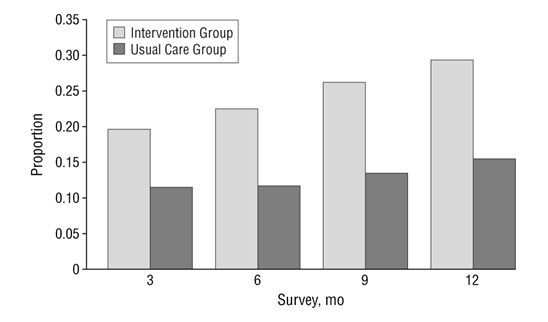

Why the dramatic increase in psychoactive medications by non-psychiatrists? Patients referred to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for panic are usually not satisfied. JAMA Research confirmed what doctors were hearing back from patients. The research showed only one person in six treated with CBT became panic-free ("Usual Care Group" dark gray in the graphic below).

When meds were added, the remission rate nearly doubled ("Intervention Group" light gray). The researchers advised, "Our intervention for panic disorder, a combination of CBT and antianxiety medication . . . resulted in substantially better outcomes than did usual care" (CBT).

The 2005 study may have contributed to the doubling of benzodiazepine prescriptions by primary care physicians.

After all, to a non-psychiatrist, adding benzodiazepine may have looked like a no-brainer: Go ahead and do what the researchers seemed to recommend. But psychiatrists don’t regard adding a benzodiazepine as wise at all. The Veterans Administration has banned them, except for patients already addicted, and there is a program in place to aggressively move those already addicted off the benzodiazepine.

Because of their experience, psychiatrists are not quick to prescribe a highly addictive medication associated with overdose as a way to chase a benefit that is unlikely to hold up. Dr. Anna Lembke, a psychiatrist and director of addiction medicine at Stanford University, told CNN, "People develop a tolerance, and they need more and more to get the same effect. The problem is in the long term, they lead to more problems than they solve,"

Addiction

What does "more problems than they solve" mean? One problem is addiction. Benzodiazepines are notoriously difficult to withdraw from. To mitigate the risk of seizure, withdrawal should be supervised.

Tolerance

A second problem is tolerance. When tolerance develops, the prescribed dose unexpectedly fails to control panic. In a state of panic, a person who is ordinarily savvy may take dangerous, irrational action.

For example, a new fear of flying client told me she flew for years using Xanax. She said it worked well for her. But, without warning, she panicked during a flight. She took another dose. Since benzodiazepines take time to work, relief did not arrive quickly enough. Emotionally overwhelmed and frantic for relief, she turned to alcohol. She quickly downed a few shots.

I was alarmed at how casually she spoke of mixing Xanax and alcohol, and said, "Don't ever do that. It's dangerous. A person can tolerate a lot of alcohol alone or a lot of Xanax alone, but a moderate amount of each together can cause you to stop breathing."

"I know," she replied. "I'm a nurse. But I was desperate. All I wanted was relief."

Overdose Risk

She boarded her flight expecting Xanax to protect her has it had before. Unknowingly, she had developed a tolerance for Xanax. During the flight, a full-blown panic attack took place. Overwhelmed and unable to think rationally, she reacted in a way that went against everything she knew as a nurse.

As tolerance develops, benzodiazepines set an invisible trap. Dr. Lembke points out, "If they worked long term, there would be nothing wrong with it, but they don't and then they cause all kinds of harm." Overwhelm occurs when meds unexpectedly fail to control panic. Frantically searching for relief from panic—after panic has made it impossible to think rationally—partly explains the rise in benzodiazepine-related deaths from 1,135 in 1999 to more than 11,537 in 2017.

CBT is unsatisfactory because of its low panic remission rate. Panic is not ordinarily a fatal condition. But, when a person relies on a benzodiazepine for protection against panic if that protection unexpected falls apart, a full-blown panic attack places the person at risk of irrational action that results in an unforeseen and unintended fatal overdose.

A More Effective Way to Stop Panic

Benzodiazepines are more difficult to justify now that an effective way to treat panic is available. A panic control method developed in the SOAR fear of flying program is five times more effective than CBT. When applied to panic in day-to-day situations on the ground, it produces a remission rate of up to 87 percent.

Research

An email was sent on August 27, 2016, to 293 people who had enrolled in one of the SOAR fear of flying programs. The text of the email is as follows:

To determine SOAR's effectiveness in stopping panic, if you have time, please answer four questions. Just list 1, 2, 3, 4, and your "yes" or "no" answer, and email your answers back.

Before SOAR

1. Did you experience panic on the ground?

2. Did you experience panic in the air?

After SOAR

3. Do you experience panic on the ground?

4. Do you experience panic in the air?

There are three SOAR programs. The full-length course is composed of nine hours of instructional video and two hours of counseling by phone. A shorter course has four-and-a-half hours of video instruction. A still shorter course has three hours of video instruction. Both of the shorter courses offer an optional 30-minute counseling session by phone.

Results of the Study

Full-Length Course With Two Hours of Counseling

- Results on the ground: 15 experienced panic on the ground prior to the course; 13 (87 percent) reported no panic on the ground after the course. One reported "small" panic; thus, 93 percent became panic-free or improved.

- Results in the air: 21 experienced in-flight panic prior to the course; 17 (81 percent) were panic-free in the air after the course. One reported "less severe" panic, thus 86 percent became panic-free or improved.

Shorter Courses With Counseling

- Results on the ground: 16 experienced panic prior to the course; 10 (50 percent) reported no panic afterward. Less panic was reported by 3; thus, 81 percent were panic-free or improved.

- Results in the air: 28 experienced in-flight panic prior to the course; 19 (68 percent) were panic-free when flying afterward. Less panic was reported by 4, thus (82 percent) were panic-free or improved.

Shorter Courses Without Counseling

- Results on the ground: 49 experienced panic on the ground prior to the course; 30 (61 percent) reported no panic afterward. Less panic was reported by 6; thus, 73 percent were panic-free or improved.

- Results in the air: 61 experienced in-flight panic prior to the course; 41 (67 percent) were panic-free when flying afterward. Less in-flight panic was reported by 12; thus, 87 percent were panic-free or improved.

Commentary

Though none of the SOAR Courses were directed toward alleviating panic on the ground, the intervention aimed at in-flight panic generalized to reduce panic dramatically on the ground.

The book Panic Free: The 10-Day Program to End Panic, Anxiety, and Claustrophobia adapts the method that controls in-flight panic to control panic on the ground. Accessible in book and audio-book form, the method can potentially increase the number of people who become free of panic as well as reduce unintentional overdose.

Readers who are good students, particularly if introspective, can get good results on their own. Some readers need to be guided by a therapist. The book includes an afterword for therapists written by Stephen Porges, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, past president of the Society for Psychophysiological Research, and recipient of a National Institute of Mental Health Research Scientist Development Award. Panic Free is based largely on his neurological research.

For too long, attempts to control panic have focused only on reducing hyper-arousal. Porges's discovery has made it possible to counteract hyper-arousal by automatically activating the parasympathetic nervous system. The method detailed in Panic Free, based on Porges's discovery, has already enabled over 10,000 flight phobics to control anxiety and panic automatically.