Politics

The Path to Power

How to become British Prime Minister.

Posted September 1, 2022 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- The new resident of 10 Downing Street will be the twelfth of the last fifteen British Prime Ministers to have graduated from Oxford University.

- Academic excellence isn't necessarily the foundation of the university's success in British political and establishment life.

- Oxford Union debates are modelled on the UK Parliament and mimic its debating style, giving future politicians key rhetorical skills.

- Exposure to current and future leading politicians through the years at Oxford give its students a huge advantage toward a career in politics.

On Monday the United Kingdom will have a new Prime Minister. Either Oxford graduate Rishi Sunak or, the bookies’ favourite, Oxford graduate Liz Truss, will walk through the famous black door of 10 Downing Street.

Whoever wins will replace Oxford graduate Boris Johnson, who succeeded Oxford graduate Theresa May, who succeeded Oxford graduate David Cameron.

Can you spot the pattern here?

The Oxford Effect

The Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, collectively known as Oxbridge, are renowned the world over. But it’s Oxford that dominates the British political sphere and wider establishment, with 29 of the 56 prime ministers to date, 12 of the 15 since 1945 (including the imminent incumbent), compared to 14 who went to Cambridge. Just eight didn’t attend university at all.

According to the Elitist Britain report in 2019, the UK’s power structures are dominated by a narrow section of the population: the 7% who attended independent schools and the roughly 1% who graduated from Oxbridge. The report found that 31% of politicians attended Oxford or Cambridge—and 57% of cabinet ministers.

What is it about Oxbridge generally, and Oxford University in particular, that creates such a compelling path to the top of the UK’s political establishment?

With Oxford and Cambridge’s reputations for academic excellence, it might be argued that the two universities both attract and produce the brightest minds and that it is thus only natural that many of their graduates would go on to become senior figures in public life.

Many people point to the predominance of Oxford’s Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) degree that seems to have dominated Westminster in recent years (both Truss and Sunak are PPE graduates). But, as renowned political historian Anthony Seldon points out, “Although it may have dominated the Cabinet, its influence in 10 Downing Street is not as strong. Since 1900, three prime ministers have studied PPE: the same number who have studied science, technology, engineering and mathematical subjects and considerably fewer than the seven who have studied history or classics. In addition, two post-1900 prime ministers studied modern languages and one each studied philosophy, law, and geography.”

Simon Kuper, Financial Times columnist and author of Chums, How a Tiny Caste of Oxford Tories Took Over the UK, goes further in rebutting its influence at the highest level: “The PPE degree is unusually superficial, even by the standards of Oxford degrees. The whole Oxford degree is typically 72 weeks, that’s less than a year and a half. With PPE you divide that over three completely different subjects, so it is quite superficial.”

The Art of Rhetoric

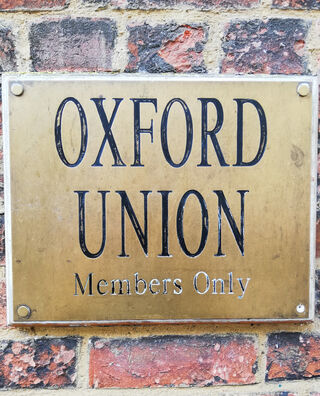

For Kuper, more important than the quality of the education is extracurricular activity, in particular the Oxford Union Debating Society. “This is where you learn the kind of rhetoric that is prized in the Commons”, he said. “The Oxford Union is a kind of nursery of the Commons, a children’s parliament. You have the same facing of the benches, the same voting ‘ayes’ and ‘noes’, people shouting points of order.

“So, when you get into the Commons, they find it very familiar.”

Rhetorical training in the Oxford Union is seen by Kuper as the foundation of future Parliamentary success. Boris Johnson is seen as typifying this style, putting delivery before substance and detail. Kuper observes, “The rhetoric you learn is this jesting, jousting, ignoring the other person’s arguments, being funny, being entertaining. And Boris Johnson symbolises the Oxford Union qualities to the point of parody.”

In Chums, Kuper argues that the Oxford style of education, being able to argue for a point in front of your tutor, puts cramming and rhetoric ahead of a grasp of detail. “Oxford teaches you above all to speak well and write well, even when you don’t know much about what you are talking about,” he told me. “The ability to speak well and present is primordial in British politics. It’s very hard to reach the top without it.”

Fellow Financial Times journalist Ed Luce points to “people who mastered the art of delivering their assignments in limpid prose that they had only started working on overnight. If you learn young how to slip past Oxford’s best scholars, the rest of life ought to be a doddle.”

Well Connected

In addition to the ability to present and make a strong argument, another key ingredient for success identified by the Elitist Britain report is the ability to make the right connections from a young age. The predominance of Oxford University in British politics naturally means that many politicians find themselves surrounded by their university contemporaries as they climb the ladder.

Former British cabinet member Michael Heseltine remembers studying alongside future political giants and meeting the leading lights of his day when he was at Oxford. He told the BBC, “Oxford presents every opportunity for political exchange and competition; the political parties are very active in their student equivalents. Just the experience of being able to spend so much time in a world where you meet other politicians, not just as students but also as speakers. There are hugely impressive opportunities for undergraduates to meet people at the top of their tree, and that includes household names in the world of politics."

And then there is the pipeline effect. As Oxford professor of social geography Danny Dorling explains, "One effect of going to Eton and going to an Oxford college is that the impetus to go on and do something big is very high. You will know that people have gone on to achieve great things.”

References

Elitist Britain 2019, The Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission.

Seldon, Anthony. Starters for Number 10, Times Higher Education, 8th June 2017.

Kuper, Simon. The Connected Leadership Podcast, 5th September 2022.

Authers, John. Britain Still Can’t Look Past Oxford for its Leader, The Washington Post, July 21st 2022.

Nimmo, Joe. Why Have So Many Prime Ministers Gone to Oxford University? BBC News 5th October 2016.