Bias

How Well Do We Really Know Our Partners?

New findings on "tracking accuracy" and "directional bias."

Posted September 26, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Research shows that people have a positive bias when evaluating their partners.

- We can inflate our perceptions of a partner's good qualities while still accurately knowing where they stand relative to others.

- We tend to be relatively accurate in our assessments of our partners' objective abilities.

How well do we know our romantic partners? We have often spent years living together, see each other daily, confide in each other, and have been through countless ups and downs together. In many ways, who could know us better than our partners? On the other hand, when it comes to this very important relationship, we're highly motivated to view our partners in a positive light. With so much invested in the relationship, we want to feel reassured that we're with a great person, and are highly inclined to give our partners the benefit of the doubt. If we're wearing those rose-colored glasses when we look at our partners, are we less accurate than we think? Researchers have been asking these questions for decades, and it turns out the question of how accurately we perceive our partners can get pretty complicated.

We view our partners through rose-colored glasses

Numerous studies have shown that people perceive their relationships as above average. When asked to rate how their own partners compare to the typical partner, most people rate their own partners as superior to the median partner (If people were generally accurate, researchers would expect half of the study participants to rate their own partner as below the median). We also tend to perceive our partners more positively than they perceive themselves on a variety of characteristics, and this is especially true for couples who are highly satisfied with their relationships.

But we can be accurate and biased at the same time—even about the very same traits

As described above, we tend to have an overall positive bias when it comes to how we see our partners. We generally perceive them as better than they really are—kinder, smarter, more attractive. However, we still know our partners' relative strengths and weaknesses. Studies have shown that while most people rate their partners with positive "directional bias" (that is, rate their partner more positively than some benchmark, such as the partner's own self-perceptions or evaluations of their partner made by other people), they tend to rate their partners in a way that reflects their partners' relative standing compared to others, often referred to as "tracking accuracy."

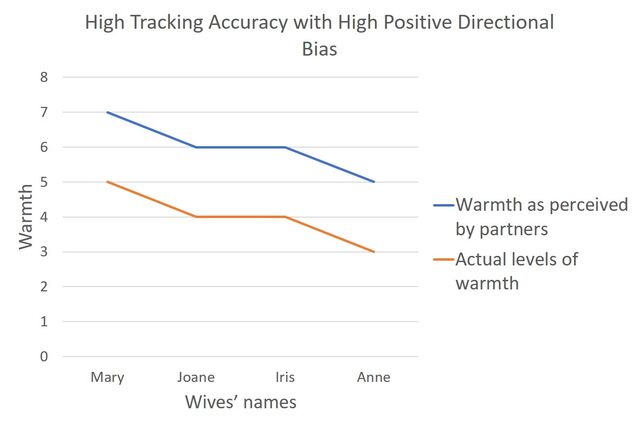

To fully understand the phenomenon of "tracking accuracy," it's useful to consider an example proposed by Garth Fletcher. The figure below shows hypothetical ratings made by four men of their wives (Mary, Joane, Iris, and Anne). All four men show positive “directional” bias, rating their wives as warmer than they actually are. However, they also show tracking accuracy because their ratings still capture each woman’s levels of warmth, relative to her place in the overall group of wives. So those with the warmest wives rate their wives as warmer than most husbands do, and those with the coldest wives rate wives as less warm than most husbands do.

Studies in which samples of couples rate their partners on various traits (such as warmth) allow researchers to assess both types of accuracy. This research finds that the average person shows positive directional bias, while also showing tracking accuracy—on the very same traits.

We’re more accurate for some traits than others

Researchers studying directional bias have found that we are most likely to inflate our partners' worth when it comes to global characteristics, and less likely to do so for more specific characteristics. For example, being punctual is one specific aspect of being reliable. That is, reliability is a more global and general trait than punctuality. Studies show that people are more likely to have inflated perceptions of broad traits, such as believing their partner is an especially good person, than more specific traits, such as self-discipline or physical attractiveness.

This makes sense because the more general the characteristic is, the easier it is to just define it in a way that favors your partner. One woman may view her partner as a kind person because he is a caring father, whereas another woman may view her partner as kind because he often helps strangers in need. These two men may have little overlap in their traits and behaviors, but both have features that could be used to judge them as being very kind.

We may be better judges of our partners' abilities than their traits

Most of the research on the accuracy of these judgments asks couples to evaluate traits that are somewhat subjective. However, some recent research has compared people's perceptions of their partners to objective measures of their abilities. In one recent study, participants completed valid, accurate measures of their intelligence, creativity, and social skills. Then the researchers asked people who knew them—their romantic partners, their close friends, and their acquaintances—to evaluate them in those four areas. The researchers found that romantic partners showed at least some accuracy in assessing their partners' abilities. In addition, romantic partners were more accurate than close friends and acquaintances and were the only group to make accurate judgments of social skills. This makes sense because performance on these specific skills is relatively objective. As we spend time with our partners, we can see where they succeed and where they struggle.

This type of accuracy is likely to be beneficial for couples. Imagine a scenario where a woman falsely believes that her husband is much more socially skilled than he really is. This overconfident woman may then encourage her husband to just go ahead and confront a co-worker with whom he has some interpersonal difficulties, confident that he'll know how to handle it—only to have the interaction blow up in his face. If she more accurately understands his social skills, she'll know where he's likely to make mistakes and be better able to help him come up with an effective strategy for dealing with the problem. Accurate knowledge of each other's abilities thus allows partners to provide more effective support to each other and to divide up tasks in a way that makes the most effective use of each partner's skills.

In Sum

When it comes to our partners, we tend to view them with a positive bias. We think they're kinder, smarter, and all-around more wonderful than they really are. However, that does not mean we are blind to their faults. We understand our partners' relative strengths and weaknesses. We show less positive bias when evaluating our partners on traits that are relatively specific, and when it comes to their objective abilities, we are especially accurate.

This combination of accuracy and bias provides a recipe for a happy and supportive relationship. Regarding our partners highly reassures us that we've chosen the right person and our regard makes our partners feel loved and valued. But we also know our partners’ specific skills well enough to solve practical problems and prevent our partners from getting in over their heads.

Facebook image: LightField Studios/Shutterstock