Suicide

Our Children Are Losing Hope

New research shows more children attempting suicide.

Posted July 8, 2019

Hope is a four-letter word we use all the time. Think about it. How many times have you used the word today? Hope means something different to everyone—but did you know that hope can be learned? Why do some of us have more hope than others? What happens when we lose hope? And how do we get it back? To find out how much hope you have, try this quiz.

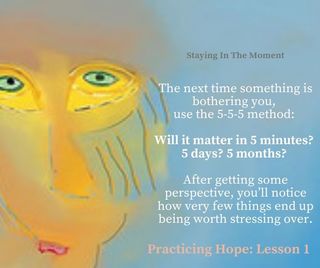

We get it back through practice. Yup—hope is a muscle and it needs to be used to stay strong and at the ready for when we need it most. Hopefulness can help us deal with complex feelings like loneliness, estrangement, and guilt. And learning how to stay hopeful can bring us more joy, happiness, compassion, even love, into our lives. One example is learning to use the 5-5-5-method when something is bothering you. Ask yourself, will this matter in five minutes? Five days? Five months? After getting some perspective, you will understand how very few things are worth stressing over.

Hope and resilience can help us when we are at a crossroads trying to understand what is in our control and what is not, what is destiny and what is a choice. Sometimes we lose hope because of untreated trauma from our childhood. When this is the case it is important to find a therapist, healer, friend, or professional who will help you transcend the memories that are locked inside your body. Treating old traumas can renew hope and give you more energy for new experiences.

Learning about hope and practicing hope can help us all respond to the crisis of death by suicide in the U.S., which is at a 50-year high. Death by suicide is the second leading cause of death for children between the ages of 10 and 19. Sadly, suicide attempts by children increased from 580,000 in 2007 to 1.12 million in 2015, according to a recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics. It is heartbreaking that the average age of a child at the time of the study was 13, and that 43 percent of the visits to the emergency room were for children between 5 and 11.

It feels quite shocking to even write this question: Why are more children attempting suicide than ever before? No one yet knows for sure, but there is some evidence that stress is infectious in families. Stress is being passed down to children and teens from their parents. In addition, bullying behaviors have increased among young people. Currently, in the U.S., 160,000 children per day stay home from school to avoid bullying by other students, 3,000,000 children per month.

Many bullying incidents are related to a child’s size, weight, or sexual identity. These children and their parents surely feel isolated, frustrated, and disconnected. And we know that isolation and loss of hope are the main issues that put us at risk for suicide. Parents and children clearly need our help. But how do we help them?

Maybe one way we can help is by learning how to open meaningful and respectful conversations about hope and the loss of hope. We can also learn how to ask for help ourselves and show others that asking for help is not a sign of weakness. We can find ways to reach out to friends and family, especially those who say they are “just fine, all good!”

Hope researchers like C.R. Snyder have shown us that hope is really about having realistic expectations, goals, and a sense of connection to others. We can meet these basic goals in our communities and help children and their parents feel hopeful. Let’s start talking about hope as a real practice, as a way to keep our children safe, happy, and feeling worthy of a future they choose.