Suicide

We Should Rethink the Doom-and-Gloom Messages We Tell Kids

Do progressive narratives make college kids depressed?

Posted May 15, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Recent years have seen an increased focus in college education on "broken world" beliefs.

- In reality for most outcomes, such as racism, misogyny, poverty and violence, the world has never been better.

- Data suggests there are meaningful correlations between progressive teaching and later depression.

- Teaching is one small part of a general doom-and-gloom atmosphere that is bad for our youth.

Mental health problems and suicides among college-aged youth have been on the rise in recent years, mirroring trends among both teens and middle-aged adults. Reading an essay on a bad year for student deaths at North Carolina State University, I was struck by one student's comment who spoke to the stress of being alive in a “seemingly broken world.” Our time, like any, has significant challenges, but according to data, there’s never been a better time to be a human being of any identity than in the modern U.S. (or other developed nations). How are our youth getting the message that our current world is so uniquely broken?

Understanding the trend in worsening college-aged youth mental health can be difficult. Consider multiple societal trends, ranging from parenting practices to changes in K-12 education, to increased fatherlessness and income inequality, and, of course, increased mental health problems among older generations. All these social trends correlate with this rise in mental health problems in young adults (screens and social media use appear to be an unlikely culprit).

One recent study found mental health problems are particularly prevalent among progressive and liberal youth as compared to conservatives. This has led some commentators, including those on the left, to worry that we may be teaching our youth to catastrophize and view themselves as victims. In particular, the recent progressive focus on negativity and the exaggeration of social ills ranging from racism to misogyny may create the illusion of a hostile and depressing world even as the well-being of the world, including these very variables, has mostly gotten better. Naturally, mental health patterns are complex, and any one thing is unlikely to be the single cause of societal patterns. Nonetheless, it is worth examining the hypothesis that our focus on negative progressive politics may be one if certainly only a partial explanation for increasing mental health concerns.

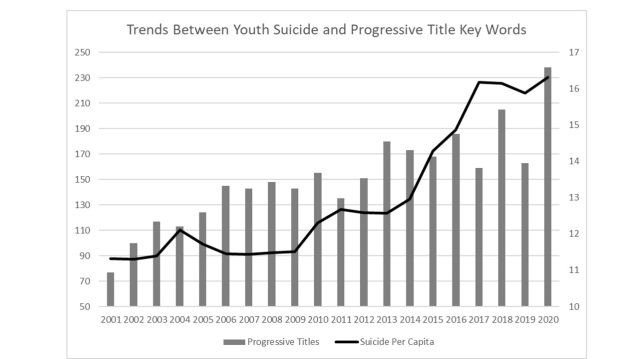

Using the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) WISQARS fatal injuries report database, suicides (arguably the best indicator of mental health trends, as it does not rely on self-report, or the trendiness of mental health diagnoses) have increased over the past two decades among college-aged adults 18-23. I also used a database of psychology research (PsycINFO) to search for research journal titles including the terms “critical race theory," “racism,” “transphobia,” “misogyny,” or “homophobia.” All these topics are worthy of consideration (though I’d argue critical race theory is a poor, unscientific theory), yet an increased focus in psychology journals may reflect a kind of progressive neuroticism and moral panic over these terms. Indeed, the evidence suggests all such prejudices have declined, often becoming vanishingly small in the United States even as progressive scholars have written on and worried over them more frequently in a kind of reverse-cognitive behavioral therapy. We can see that the correlation between the increased suicide among college-aged individuals and progressive trends in social science research as indicated by title keywords is very strong (near r = .75).

Two caveats must be noted. First, research title keywords are obviously an imperfect proxy for introductory textbooks, though it’s not unreasonable to suspect that trends in research journals would have some impact on textbooks and undergraduate teaching.

Second, demonstrating a correlation between two raw time trends is weak evidence, as ecological fallacies are common and may cause people to overestimate causal relationships between two variables. For instance, the average temperature of the planet has been increasing at about the same time as Beyonce’s income has increased, but we wouldn’t conclude Beyonce is actually making the world hotter, at least not literally.

To address this second concern, I engaged these data with what is called a time series analysis. I’ll skip the deep dive into statistics, but essentially this analysis uses a process called "pre-whitening" to reduce a tendency for time series to naturally (but meaninglessly) correlate. By looking at residuals in the time series, it’s possible to see if deviations from the pattern predict one another at different lags. For instance, if kids suddenly start eating a lot more candy, we wouldn’t expect that to have an impact on dentists’ income immediately but perhaps a year or two down the line.

Results indicated that the residuals continued to correlate concurrently (r = .751). Such concurrent correlations suggest that both factors are being driven strongly by third variables. However, correlations between progressive titles and later suicide remained strong at lags of one year (r = .602), two years (r = .417) and three years (r = .181). Beyond three years, correlations achieved triviality. This suggests a complex process by which both progressive trends in research titles (and hence teaching in psychology) and young adult suicide are driven by larger outside forces, but by which progressive teaching is predictive of future trends in young adult suicide, independent of those larger forces.

This data must, once again, be considered with three critical caveats. First, the data remain correlational and causal attributions cannot be made. Second, using journal title keywords as a proxy for undergraduate teaching is obviously a crude metric. And of course, what is happening in psychology is itself only a proxy for similar issues happening across other academic disciplines. Third, it is not possible in this data to distinguish college-bound young adults from those who did not go to college. Suicide rates are generally higher among non-college young adults than college young adults.

As such, to be very clear, this data is not sufficient to determine a causal mechanism between progressive trends in education and youth mental health. Given so many other trends that fit society’s larger mental health downturn, it’s entirely possible this may prove, like social media, to be a red herring. However, it’s enough to suggest there may be an important hypothesis here worthy of more careful investigation. Whether or not this should prove causal for mental health concerns, even in a small way, at the very least progressive trends in college teaching present a lost opportunity to correct people’s misimpressions that may contribute to neuroticism and despondency, even if these primarily come from other sources. Put simply: perhaps we should be thinking more carefully about the doom and gloom messages we’re telling our kids about the world.