Media

Social Media and Youth Mental Health

The evidence remains unconvincing.

Posted April 17, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Many assume social media use is linked to youth mental health problems.

- Too often, youth mental health is considered in isolation of the mental health of their families.

- Evidence remains weak that social media is causing mental health problems among youth.

- Larger societal issues may be causing mental health issues among all age groups.

Valentine’s Day 2023 saw congressional hearings focused on issues regarding social media and youth health. Several people and organizations, including the American Psychological Association (APA), testified that social media harms youth. No one who was skeptical of this claim testified.

The testimony was often stark. Emma Lembke, founder of Log Off, testified that “…unregulated social media is a weapon of mass destruction that continues to jeopardize the privacy, safety, and wellbeing of all American youth.” The APA's Chief Science Officer Mitch Prinstein testified that social media may exploit biological vulnerabilities in youth, increasing loneliness, risk-taking behavior, and other mental health issues or exhibiting effects similar to substance abuse.

These statements are frightening to parents. Yet they also conflict with considerable science in this field, which has largely failed to find clear relationships between social media use and mental health outcomes.

Last year, a large group of media psychologists from the United States, United Kingdom, and Ireland, including myself, published a large meta-analysis of studies examining screen time and social media impacts on mental health. We found little evidence social media or other screen use worsens mental health. Ironically, our paper was the most-read paper in any APA journal last year but Dr. Prinstein didn’t mention it in his testimony.

As is often the case with a new field of science, evidence is mixed and scientific opinions differ. However, the public deserves to know that a great number of scientific studies have failed to link social media use to mental health in youth or young adults.

Other countries, such as the UK, never saw a burst in suicide around the time social media became widespread. This would be odd if social media were indeed a “weapon of mass destruction.” In fact, suicides among youth fell during much of the past decade and a half in the UK.

Yet in the U.S., teenagers, including teen girls, are undoubtedly experiencing a mental health crisis. What else could it be?

Part of it, of course, is that many people, not just teen girls, are experiencing a mental health crisis in the US. By looking at teens in isolation, we’re misdiagnosing the problem.

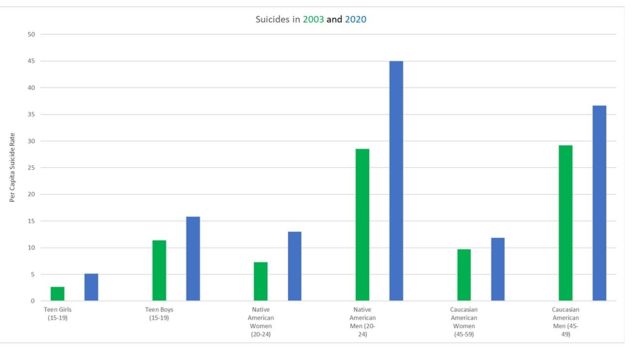

Our current narrative is similar to the old Indian parable of the blind men and the elephant. By only looking at teen girl suicides and mental health, it seems logical to wonder if social media may be a culprit. However, looking at Centers for Disease Control (CDC) data, teen girl suicides, though increasing in recent years, remain rare. By contrast, both the overall suicide rate and increases in suicide are much higher in other groups—with mid-20s Native American men and late 40s/early 50s Caucasian men having among the worst suicide rates. Something else must be going on.

In my work, I find the best predictors of teen suicidal ideation are exposure to bullying, but also experiencing suicides in their own social networks, including families. Pain is likely intergenerational—but by focusing on teens in isolation and obsessing over social media, we’re missing this step.

Further, there is little evidence social media is "addictive" in the same sense that psychoactive substances are. In investigations of technology overuse, we typically find that tech overuse is a symptom, not a cause, often driven by stress instigated by parents and schools. It’s probably more comforting to blame social media—but in reality, it’s apparent that adults and other teens are the larger sources of teen stress.

We need more data, but I suspect the rise in youth mental health problems is due to several things. First, it’s intergenerational. Kids are in pain because their families are in pain.

Second, many changes in parenting and school practices over the past few decades have not been constructive. We've increasingly shielded kids from opportunities to develop resilience and independence on the one hand, while simultaneously expecting them to achieve more and more in their high school years to get into college on the other.

Third, educational practices that portray society as wholly racist and oppressive, despite evidence to the contrary, may have increased neuroticism in youth. This likely includes some “anti-racist" microaggression or DEI instructions, which often backfire. Fourth, specific body blows such as the 2008 recession and the 2020 COVID epidemic also likely played a role.

Technology moral panics are nothing new. We're just ending one on video game violence (not linked to societal violence, it turns out), and are simply failing to learn the lesson with social media. By repeating the same cycle—blaming technology, ignoring other factors, making false claims of research consistency, and employing hyperbole like the phrase “weapons of mass destruction”—we risk doing real harm by distracting society away from the real causes of our mental health crisis.