Magical Thinking

Mermaids and Vampires: Do You Know Which One Is Real?

Watching so-called "science channels" would certainly leave you wondering.

Posted August 26, 2019

There are hundreds of TV channels on my satellite that I never watch. Once in a while, when my favorite shows are in reruns or taking a summer break, I check out some of those unwatched channels to see if I might have overlooked something.

I haven’t. Sanctimonious TV preachers are every bit as offensive as I remembered them; I have no interest in a beauty makeover (too late for me); and I don’t want to get rich collecting coins. And I’m bored by endless loops of Chubby Checker or Fabian singing their golden hits from half a century ago.

But there is one channel that I often give a second look during these “just to be sure” surveys. It’s called Animal Planet. The trouble with that destination is the disturbing mix of fact and fiction. You never know if you’re going to watch stuff about bears and crocodiles or dragons and mermaids.

And there’s almost no difference in the way they’re presented. Mythical creatures, real animals—they’re all getting the same pseudo-documentary treatment on Animal Planet, and there’s always a “scientist” encouraging you not to doubt what you see.

Some of it seems pitched to reasonably intelligent, curious people like you and me. But often the very next show is geared to certifiable morons—people whose ability to think critically has been seriously impaired, either by culture or genetics.

The usual example of this kind of programming is a Search for Bigfoot special, which combines obviously faked footage with eyewitness claims that “Ah seen one this mornin’. He had hair all over like a GO-rilla but he seemed kinda human-like. Ah got off a coupla shots but he was too quick for me.” After some blurry photos and testimonies by folks you wouldn’t want your sister to date, these documentaries conclude that Bigfoot’s existence is proven, but the government is actively covering it up.

Last night’s documentary was a Search for Mermaids (actually called Mermaids: The Body Found—not to be confused with its sequel, Mermaids: The New Evidence.) Apparently, Bigfoot programming has run its course or is taking a summer break, and these beauties of the deep (aka "fish-bodied humanoids") represent fresh meat to the gullible.

And don’t underestimate their numbers. Animal Planet set a ratings record for its mermaid sequel, drawing in 3.6 million viewers [Hibberd, 2016]. True to form, last night’s show contained a nautical version of the backwoods yokels, as well as some “scientists” (played by actors) who praised each other’s documentary footage. I was waiting for them to use clips from the 1984 film Splash with Darryl Hannah and Tom Hanks as further proof, but cooler heads (or lower budgets) must have prevailed.

Here’s the problem: Immediately following this quest for mermaids, there was a search for undersea vampires. More of the same, I assumed. But no! Incredibly, this show was worth our attention and might convince me to take Animal Planet off my visual scrap heap.

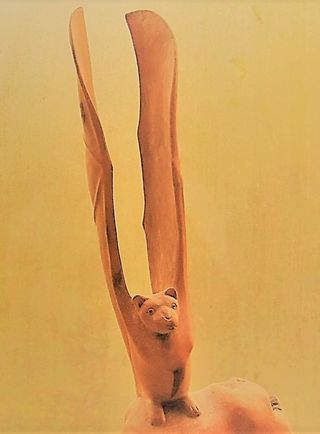

Here’s why: Unlike mermaids, vampires exist. I don’t mean Count Dracula or Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee or any of the modern-day incarnations of men and women who prowl by night, waiting to sink their fangs into your throat. I mean real creatures who have evolved to sustain themselves on the blood of their victims. There’s even a name for that dietary trait: hematophagy. It’s every bit as real as being a carnivore or herbivore.

There are three species of bats that feed solely on blood: the common vampire bat, the hairy-legged vampire bat, and the white-winged vampire bat. See? Science isn’t so boring. Why go looking for Bigfoot when there are hairy-legged vampire bats?

Vampire bats (they do not take human form) live in Central and South American forests and often attach themselves to cattle, who offer little resistance. Even our summertime nemesis, the mosquito, is a vampire of sorts. He may not have suave manners or present himself in a black cape, but he does land on your bare flesh, briefly anesthetize a small region of skin, and suck a small quantity of your blood before exiting the scene. Nothing supernatural. He’s real, and so are those South American vampire bats who tend to leave humans alone.

This documentary on undersea vampires was presented as a mystery show, with a beginning, middle, and end. The production values were quite high, and as I’ve since learned, it’s part of the highest-rated series (River Monsters) and host (Jeremy Wade) on Animal Planet. In fact, prior to its recent cancellation, the show had run since 2009 for a total of 57 episodes and 44 specials. That’s success by any reckoning.

The mystery of the undersea vampires was solved in the last ten minutes. The elusive bloodsucker, who preyed on human swimmers and many fish species, was revealed to be a lamprey, an ancient (it goes back 360 million years), eel-like, jawless fish that can grow to over three feet long. There are over 38 species of lamprey, including some extinct ones, and they really exist.

The footage wasn’t grainy and indistinct. It was quite clear and extremely creepy. The interviews were with people who sounded like they had more than two neurons to rub together. And so by the end of the episode, we had learned something about our planet’s natural history. Admittedly, these are pretty scary critters, both in how they look and how they make a living. But there’s nothing supernatural about them, no alien invasions and no government conspiracies swirling around them.

Like it or not, Animal Planet and Jeremy Wade managed to slip a little bit of science to its viewers. It’s true most of the audience had to be drawn in with lurid titles. If you check the schedule, you’ll find an abundance of words like “monsters,” and “invaders.” Indeed, many of the episodes on the River Monsters series, have titles that rival the names of old cliffhanger movie serials or B-movie science fiction from the 1950s. Titles like The Invisible Monster (1950) or Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959) or Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) come to mind—and those are all real, by the way [Davis, 2008].

So the question is: Why does science have to be dressed up to sound like a monster movie before it’s attractive to a mass audience? Learning about the real world around us seems to hold little appeal to many of us.

Tens of millions of viewers paid to watch ET and all the Alien spinoffs. No problem there. They’re called “science fiction.” Nobody’s fooling anyone. You know before you sit down to watch that these are made-up stories about made-up creatures. But when a channel (or a show on that channel) rolls out the imaginary stuff and packages it as truth to a nation of scientifically-challenged viewers who are not used to thinking critically, then we have a serious problem. The situation is ripe for what I’ve called "Caveman Logic."

Animal Planet presents itself as a “science channel,” which is a depressing thought. There are about two million animal species on Earth, but Animal Planet gives us dragons and mermaids, not to mention bigfoot. The U.S. has fallen far from its days as a world leader in science education. We are now a nation where religious indoctrination (e.g., “creation science”) sometimes takes the place of physical and biological science in high school curricula. Bigfoot and mermaids are just a small sample of the price we pay.

Packaging fiction as a documentary doesn’t make it real. In the words of journalist Brian Switek [2012], the Mermaids documentary was made “to titillate and deceive.” It succeeded on both counts. Its disclaimers couldn’t have been buried any deeper in the mix. To call viewers of these shows “gullible” is to treat them with undeserved kid gloves.

But in their defense, Animal Planet isn’t doing those viewers any favors. The “we were only fooling; it’s all just made-up stuff” message hardly stands out. Worse yet, these sensational fiction shows are mixed in with some real science, so you’re never sure how much disbelief you have to suspend.

Those River Monsters or Dark Waters series are a godsend of sorts. A taste of honey to make the medicine (actual science) go down easily. They talk about such things as DNA and offer no supernatural punchlines. No Roswell, New Mexico-like government conspiracies hovering over the story.

The natural world is full of wonders. Too many of us have been taught that science and nature are boring, and the only real thrills lie in the supernatural or extraterrestrial tales. Take a step back and think about it. If a real mermaid were found off the coast of Portugal, do you not think it would be the lead story on tonight’s network news? Would it be relegated to a “documentary” running at 4 a.m. on a cable channel, sponsored by a company selling beef jerky?

You want another example of what you’re missing? Google “angler fish.” They are fish who fish. If you try to make up such a creature, it’s doubtful you’d come up with anything as scary as the real thing. Long, tubular lures growing out of their heads glow in the dark (they live deep in the water where the sun doesn’t shine).

The angler fish swims silently through its murky habitat, using its glowing lures to troll for prey. And who could resist them down there? Then long, sharp teeth shunt their fresh-caught dinner directly to their stomachs. Their teeth have a second function. They also clamp shut like a cage to trap their living meal until it’s ready to be eaten.

Does this creature sound boring to you? On top of everything else, these critters are feminist-friendly. The lowly males of the species are sometimes less than an inch long. The females, on the other hand, can grow to two and a half feet. A deadly PC fish, barely known by anyone on earth who doesn’t happen to live two or three miles below the surface.

But up here on dry land, we’re stretched out on our couches, uncritically watching “fake-u-mentaries” or “docufiction” sponsored by sausage companies.

References

Davis, Hank (2008). Classic Cliffhangers: Volume 2 (1941-1955). Maryland: Midnight Marquee Press.

Davis, Hank (2009). Caveman Logic: The persistence of primitive thinking in the Modern World. New York: Prometheus Books.

Hibberd, J. (2016). Mermaid hoax drowns Animal Planet’s ratings record. Entertainment Weekly, May 28 2016.

Switek, Brian (2012). Mermaids embodies the rotting carcass of science TV. www.wired.com/2012/05