Animal Behavior

Why Certain Dogs Learn More From Watching People

How independent and cooperative breeds solve problems.

Updated June 28, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Social learning refers to skills acquired by watching other individuals performing relevant activities.

- Not all dog breeds benefit equally from observing potentially helpful actions from a human.

- Dog breeds may be grouped into cooperative working breeds and independent working breeds.

How did you learn most of the important skills that you use in your everyday life? If you think about it, you will probably come to the conclusion that you gained this knowledge simply by observing other people, such as your parents, teachers, or friends, and then repeating their actions. You learn language by listening to someone speak it and copying those sounds. You learned how to button your shirt, tie your shoelaces, or use a can opener, by observing another person doing these things.

Psychologists call this social learning, not because it involves learning social manners, customs, or communication, but because it refers to a type of learning that is socially transmitted or socially facilitated. This kind of learning and performance seems to be unique to the most evolutionarily advanced animals that live in a complex social environment, and that includes dogs.

Dog Breeds May Be Divided Into Functional Groups

There is a lot of evidence to show that dogs watch the deliberate or casual actions of human beings or other dogs and use the information that they gather from these observations to guide their own behaviors. However, a new study by Petra Dobos and Péter Pongrácz of the Department of Ethology at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary, suggests that not all dog breeds benefit equally from observing potentially helpful actions from a human demonstrator.

For the purposes of this investigation, these researchers utilized the idea of sorting dog breeds into two functional groups: specifically dogs who were selected for cooperatively working with humans (such as retrievers, herding dogs, and a variety of sporting breeds) versus dog breeds who mainly work without direct human guidance, here referred to as independent working dogs (which would include most terriers, livestock guarding dogs, hounds, and Spitz or Nordic breeds).

They were not the first researchers to hit upon this idea of the functional division of dog breeds. For example, in 1998, I noted that several breeds of dogs clumped together into what I called the "independent" or "self-assured" groups in direct comparison to more cooperative breeds of dogs that fell into what I called "friendly" or "clever" groups. Furthermore, Kathleen Morrill of the University of Massachusetts and her associates sequenced the DNA of more than 2000 dogs and found that biddability (how well dogs respond to human direction) was a heritable characteristic that differed strongly among dog breeds. However, Dobos and Pongrácz were the first to suggest that perhaps cooperative dog breeds were more likely to benefit from simply observing the activities of a person who might provide information as to how to solve a particular problem.

The Detour Problem

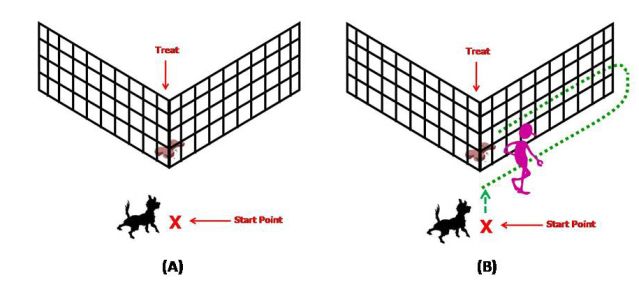

For a number of years, Pongrácz and his associates have been studying whether dogs can learn to solve a problem that involves finding a particular path to a reward by merely observing someone else successfully complete it. The experimental arrangement that they often use is a large V-shaped wire fence, about 3 meters or 10 feet long, with the point of the V facing toward the dog as can be seen in Figure A. A highly desirable treat or toy is placed at the point behind the fence. Psychologists call this kind of situation a "detour problem."

It is an interesting test because the solution requires the animal to move some distance away from its goal before going back to it. In this case, a dog must move down the side of the V-shaped fence for a good distance (which seems to take him farther away from the treat he wants) and then eventually he can reach the end of the fence and be able to curve around and enter the V from the open side and reach his goal.

Although initially, dogs experience difficulty in solving problems involving such detours, they usually can learn to solve these tasks by trial and error. That trial and error learning, however, is slow and the dogs often need to blunder their way around until they successfully find their way around the fence. It is not unusual for them to try several times before they catch on and have that “Aha!” experience. Once they achieve this insight they quickly and reliably move around the barrier to get their reward.

Suppose that instead of just letting the dog poke around until he finds a solution, he is kept in one place and allowed to watch a human taking the correct path down the side of the V-shaped barrier and in through the back to get the treat (Figure B). Many dogs can learn what to do from observing a person performing the correct behavior and, when given the chance, they solve the problem quickly, usually in one attempt.

Some Dogs May Watch While Others Do Not

In this study, the researchers tested close to 100 dogs, 18 breeds from the independent working group and 16 breeds from the cooperative working group. Each dog had one minute to complete the task and was tested three times. For some dogs the second and third tests were preceded by having a human demonstrate how to get around the detour. As had been predicted by the researchers, the cooperative dog breeds gained a clear advantage in this situation if they watched a human perform the correct action. Unlike the independent dog breeds, cooperative dogs perform faster in subsequent detour tests compared to their baseline trial. The independent dog breeds showed no benefit or increased speed in solving the detour problem following the demonstration.

The researchers conclude that "cooperative dog breeds, regardless of their ancestry and training levels, utilize human demonstration more effectively." They further note that the functional (genetic) selection for cooperative work with humans seems to be the decisive factor behind their results. Thus it might be beneficial for you to act out the solution to a problem if you own a Labrador Retriever, however, if you have a Scottish Terrier you might be wasting your time.

Copyright SC Psychological Enterprises Ltd. May not be reprinted or reposted without permission

Facebook image: UNIKYLUCKK/Shutterstock

References

Dobos, P., & Pongrácz, P. (2023). Would You Detour with Me? Association between Functional Breed Selection and Social Learning in Dogs Sheds Light on Elements of Dog–Human Cooperation. Animals, 13(12), 2001. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ani13122001

Coren, S. (1998). Why We Love The Dogs We Do. New York: Free Press (pp i-xii, 1-308). [ISBN: 0684839016]

Morrill, K., Hekman, J., Li, X., McClure, J., Logan, B., Goodman, L., Gao, M., Dong, Y., Alonso, M., Carmichael, E., Snyder-Mackler, N., Alonso, J., Noh, H. J., Johnson, J., Koltookian, M., Lieu, C., Megquier, K., Swofford, R., Turner-Maier, J., White, M. E., … Karlsson, E. K. (2022). Ancestry-inclusive dog genomics challenges popular breed stereotypes. Science (New York, N.Y.), 376(6592), eabk0639.