Health

Which Breeds of Dogs Are Best for Your Health?

Simply owning a dog lowers your health risks, but some breeds do a better job.

Posted November 23, 2017

According to research, owning a dog may be associated with better health and longevity. However some new data suggests that certain dog breeds may be more beneficial than others.

Over the past decade it has become clear that people who own dogs also seem to benefit from improved health, both physically and psychologically. In fact, in 2013, a special report issued by the American Heart Association concluded that dog ownership is most likely associated with decreased cardiovascular disease risk. Some new data published in the journal Scientific Reports seems to conclusively prove these earlier reports of the benefits of dog ownership.

This research comes from the investigative team headed by Tove Fall, professor of epidemiology at Uppsala University in Sweden. The size and the scope of this new data collection has never been equaled by any other study addressing the question of the health benefits of owning dogs. The research group took advantage of the fact that everyone in Sweden must carry a unique personal identification number which allows their health data to be tracked. All of their hospital visits are recorded in a set of national registries, and there is also a national registry of deaths and cause of death. The researchers gathered the health data from all Swedish residents aged 40 to 80 years who had no evidence of prior cardiovascular disease on January 1, 2001. The resulting sample of 3.4 million people was then automatically enrolled in the study.

The date January 1, 2001, was chosen, because that was also the date that it became a legal requirement for every dog in Sweden to have a unique identifier (ear tattoo or microchip), and each dog's information is also entered into a set of registries which link that dog's information to its owner. In this sample of over three million people, 13 percent kept dogs, and their health information could be linked to information about the dogs they owned. This now allowed a comparison of the health information of dog owners and those who did not own dogs. This huge sample of people was then tracked over a period of approximately 12 years.

Given the large number of people tested, and the length of time that individuals were followed, it seems likely that any conclusions which were reached would be very stable and believable.

Based on their data collection, the researchers ultimately concluded that dog ownership has a powerful effect on longevity. Overall, they found that owning a dog reduced the likelihood that an individual would suffer from cardiovascular disease by 26 percent and reduced the probability of dying from any cause over the 12-year period by 20 percent.

The beneficial effect of a dog seems to vary depending upon whether an individual is living by himself or in a multiple-person household. If you are a person living alone, the effects are much greater. Thus, the incidence of cardiovascular disease is reduced by 15 percent in a multi-person household and by 26 percent for a person living alone. Similarly, your risk of dying from any cause over the 12-year period is reduced by 11 percent in a household with more than one person and by an amazing 33 percent for a person living alone.

In the world of medical research, where improvements in longevity by 5 percent are considered to be very large, results showing health benefits of the size found here for dog ownership must be considered to be huge. Thus, it is not surprising that the mainstream press picked up on these recent results, and they were given headlines in science sections of newspapers and featured on national news broadcasts. This is proper, because these results are of such a magnitude; however, the media seems to have missed an important feature of these findings — namely that the health benefits seem to vary across different breeds of dogs.

It is likely that the breed differences were not explored by the media, because the data presentation in the report employed the typically dense technical jargon and statistical treatments that appear in major scientific journals. To interpret the breed differences, one would have to slog through some unfamiliar statistical concepts such as hazard ratios and confidence intervals and that sort of thing. Also, the breed groupings used in the report may seem to be a bit strange to people in the English-speaking world. Still, if you do the analytic work, there are some interesting differences to be found pertaining to the health benefits provided by the various dog breeds.

Since this research was conducted in Sweden, it is not surprising that the dogs were grouped in the categories established by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (the World Canine Organization). It is usually abbreviated as the FCI, and it is the largest international federation of kennel clubs. The headquarters of the FCI is in Thuin, Belgium. The FCI breed groupings are used throughout Europe and most of Asia, and they differ markedly from the breed groupings used by the American, Canadian, and British kennel clubs.

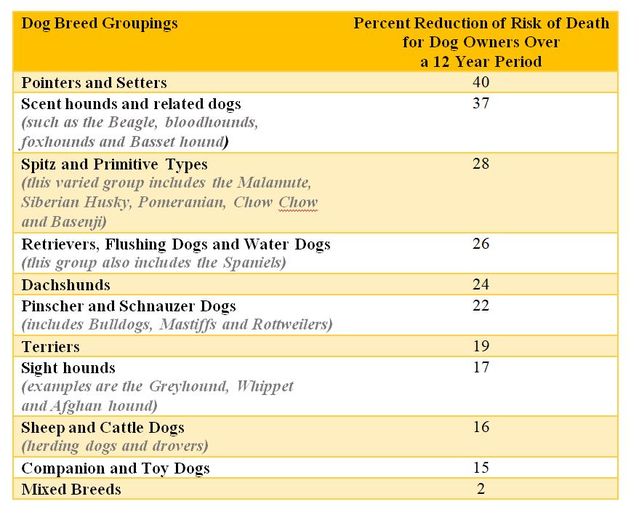

The data was not presented for individual breeds, but rather for the FCI breed groupings. A number of statistical procedures were used in the data presentation. Perhaps the most useful is based on the calculation of the rate for death from all causes, adjusted for sex, marital status, presence of children in the home, population density, area of residence, region of birth, income, and number of persons in the household. Using these numbers, it was possible for me to convert the hazard ratios into a percentage reduction of the risk of death for a dog owner over a 12-year period. The results in the table below show the different health benefits associated with owning a dog in each of the FCI's 10 different breed groupings.

Sporting or hunting dogs (pointers, setters, retrievers, spaniels and scent hounds) seem to provide the highest levels of health benefits and the greatest protection against early death. Why certain breeds have a better effect on the survival rate of their owners is not clear; however, there are hints.

The best guess for why dogs improve our health has to do with the problem of loneliness. A number of psychologists have warned that loneliness is as bad for human health as long-term illness. One survey in Britain showed that if you are one of the 1.1 million British people living alone, then you are 50 percent more likely to die prematurely, compared to people with live-in companions or good social networks. That would make loneliness as harmful to health as diabetes. The lead researcher in this current study, Tove Fall, suggests that "If you have a dog, you neutralize the effects of living alone."

Dog breeds differ in terms of their sociability and friendliness. Thus, it is interesting that three out of the four breed groupings with the highest health benefits include many of the most "kissy-faced" and sociable of the dog breeds. A dog with a high desire for social interaction would definitely help to counteract feelings of loneliness to a greater extent than having a dog which tends to be a bit standoffish. Such a companionable, playful, and lovable dog would have the greatest impact if you are living alone, or are in a household where you do not get a lot of human social support. However, all of the dog breeds do provide a significant reduction in the risk of death and cardiovascular disease.

As I write this I find myself thinking of the French saying, "Langue de chien, langue de médecin," which translates to "A dog's tongue is a doctor's tongue." Certainly these new data seem to say that a dog's presence has a medicinal effect that promotes longevity.

Copyright SC Psychological Enterprises Ltd. May not be reprinted or reposted without permission.

Facebook image: valleyboi63/Shutterstock

References

Mwenya Mubanga, Liisa Byberg, Christoph Nowak, Agneta Egenvall, Patrik K. Magnusson, Erik Ingelsson & Tove Fall (2017). Dog ownership and the risk of cardiovascular disease and death – a nationwide cohort study. Scientific Reports, 7: 15821 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-16118-6