Child Development

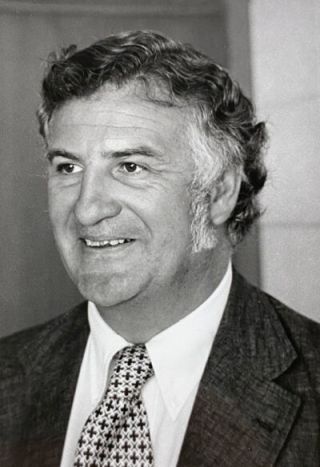

Remembering Lucius Sinks

A Personal Perspective: Dr. Lucius Sinks took on childhood leukemia.

Posted December 29, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

With Lucius Sinks’ passing, nearly all of the Cancer Cowboys are now gone.

An elite group of doctors and nurses at Roswell Park Hospital in Buffalo, N.Y., they dared to take on childhood leukemia when the disease had only a 10 percent survival rate. They did so when most of their peers and medical professionals wanted no part of the struggle.

By embracing a different mindset and advanced research methods, the Cancer Cowboys reversed the impact leukemia has upon children. As a result, the disease now has nearly a 90 percent survival rate. Sinks, along with James Holland, his wife Jimmie, and Donald Pinkel were among my major sources when I was writing Cancer Crossings: A Brother, His Doctors and the Quest for a Cure to Childhood Leukemia.

My brother Eric once suffered from acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Diagnosed in 1966, at the age of three, he was given a year to live. Soon afterward he began treatment at Roswell Park, where Sinks had succeeded Pinkel as the director of pediatrics. (Pinkel had gone on to found the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis.)

While researching Cancer Crossings, which is part family memoir and part medical narrative, I met regularly with Lucius Sinks at The Boar’s Head Inn in Charlottesville, Virginia. Our gatherings became a regular occurrence, which both of us enjoyed.

At our first luncheon, I asked Sinks if he remembered my brother, his patient from almost four decades ago. Sinks slowly shook his head. “I’ve thought a lot about it since you first got a hold of me,” he replied. “But you have to remember that I saw a lot of children during my years at Roswell Park.”

He stopped, as if to consider my question again. “Right now, I’m afraid not,” the doctor added. “But let’s just talk a while. See what the two of us can piece together.”

As a boy, Sinks grew up on the North Shore of Boston. In the winters, skating and playing hockey became one of his first passions. When the marshland near his home in Marblehead froze, he became adept at dodging between the cattails and tall grasses, and keeping control of the puck. Even back then he was solidly built and has no doubt that he would have excelled in the game if the family had stayed in the Boston area.

When Sinks was 13 years old, his father, Allen, suffered a brain aneurysm. Sinks was away at summer camp on Cheboygan Lake in Maine when it occurred and his father died within a few days. Today a CAT scan could have located the slight rupture in the brain and a simple procedure would have probably saved him. That was far from the case in 1944.

Even though his mother, Anna Batchelder Sinks, had deep roots in New England, she decided to move her children to Columbus, Ohio, where her husband’s side of the family had stronger ties and certainly more wealth. After high school, Sinks went on to Yale, graduating in 1953, and then to a fellowship at Cambridge in England before coming to Roswell Park in September of 1966. He was the new director of pediatrics, replacing Donald Pinkel.

“A lot of academic people were against what we were trying to do,” Sinks told me. “They really didn’t understand some of the methods we deployed against the cancer and, as a result, there was considerable resistance. Some pediatricians even refused to refer their kids to us. Many of them didn’t believe in what we were doing. Not one iota.”

I wondered if Sinks’ teachers and mentors advised him to focus on another line of medicine. If they had been like Pinkel’s mentor: urging him to steer away from a career in childhood leukemia.

“To be honest, some did. They thought they were doing me a favor. But I guess my problem was that I always liked working with kids the best,” he replied. “You see, kids always tell you how they feel. They don’t pull any punches. I soon came to appreciate that kind of honesty.”

As our first meeting drew to a close, Sinks asked if I would send him a photo of my brother Eric. “Something to jar the memory,” he says.

After the two-hour drive back to my home in northern Virginia, I emailed him one of the few family photos I have from that time. In it, the entire Wendel family lined up for the camera, with my parents and little sister Amy up front, the rest of us standing in a row of five behind them. My brother Eric was second from the left. Despite having lost his hair, that wiser-than-his-years face displays good color and he had a thin half-smile on his face.

Eric had the fairest complexion and the lightest-colored hair of us. On the waters of Lake Ontario, when we were making another crossing to the Canadian side, Mom made sure Eric wore a wide-brimmed hat and lathered on the sunblock to keep his face, arms and legs from becoming red and inflamed. While his stature and even body type seemed to swell or constrict, depending upon the meds he was on, his eyes and expressions never really changed. His dark eyes kept tabs on everything around him, and when he smiled it wasn’t all teeth and giggles like the rest of us. His grin was thin, with something always held in reserve. As if he somehow knew better.

A few days after our first lunch in Charlottesville, Sinks messaged that the photo had helped him turn back the clock, at least a little bit. He remembered my mother, who somehow remained upbeat and optimistic and determined despite the long odds and the myriad of medical procedures Eric faced.

“Unfortunately, your brother fell into the pattern of so many in our care,” Sinks wrote. “We could help them survive, often longer than expected, but it took some luck and real magic from there.”

Still, thanks to the Sinks and the other Cancer Cowboys, Eric did enjoy more time than anyone initially expected. Instead of a few months, Eric lived for eight years after being first diagnosed and beginning treatment at Roswell Park. My family has always considered that to be a great gift.