Dopamine

How Handwriting Analysis Helps Diagnose Parkinson's Disease

The value of a pen and pencil in neurology.

Posted January 21, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Most neurological disorders are diagnosed by medical interview and physical examination, not by scans or tests.

- Parkinson's disease can be distinguished from most other tremor disorders using just a pen and pencil and in less than one minute.

- The treatment of disorders like essential tremor is different from that of Parkinson's disease, making clinical distinction important.

- Digitizing tablet technology for handwriting analysis shows promise for academic research aimed at earlier detection of Parkinson's disease.

Computer keyboards have diminished the need for pen and paper in public and private life, but I still find it heart-warming to receive a handwritten letter through the post.

The skill of writing begins by the learning of a chain of intricate movements that are, through repetition and practise, transformed into a kinetic melody that no longer requires the brain to memorize the shape of indivdual letters.

People who develop writer’s cramp are able to learn to write with their other hand and their new signatures bear sufficient resemblance to the original that they are typically accepted on checks by banks. There are also some exceptional people who, following a severe head injury or after recovering from a stroke, learn to write with their dominant foot or even mouth. Remarkably, the appearance of their newly acquired script bears a recognizable similarity to their previous handwriting. Writing is a particular motor programme that is laid down deep in the basement of the brain in early childhood, and which becomes as unique as a fingerprint.

Graphology is now regarded as a pseudoscience analogous to phrenology and is no longer taken seriously as a way of divining a person's personality. The analysis of the appearance of a patient’s writing as part of the diagnostic process in psychiatry is also no longer considered useful, although it may still be helpful in providing supportive evidence for improvement during treatment for depression.

In neurology, on the other hand, observation of the act of writing, together with scrutiny of the script, is a reliable aid to the diagnosis of several common abnormal movement disorders, particularly those where Parkinson’s disease is suspected or a tremor is present. Graphology is also still used in forensic science, for example in cases of attempted fraud or blackmail.

Parkinson’s disease is one of the most common causes of physical impairment in the second half of life, leading to a poverty and slowness of voluntary movement, stiffness of the limbs, and impaired finger dexterity. There may also be a quivering of the hands, and, less commonly, a tremor of the legs and chin. In its fully established form, it is possible to distinguish Parkinson's from other trembling disorders outside the clinic setting by the distinctive shuffling, festinant gait, a frozen facial expression, and a hang dog appearance with loss of arm swing during walking.

For any person who consults me because of a diagnosis of possible Parkinson’s disease or an unclassified tremor, I always ask, "Has your handwriting changed in the last year or two? And, if so, in what way?" The answer is frequently in the negative but sometimes an accompanying family member will interject that the patient’s writing has become smaller, more untidy, or shaky. I then give the patient a pen and paper and ask them to write the following sentence in longhand:

Mary had a little lamb its fleece was white as snow

And everywhere that Mary went the lamb was sure to go

As the patient begins to write, I observe the posture of the hand, and at the same time take the opportunity to look for the emergence of trembling or muscle spasms in the non-writing hand or in the legs and face. I then spend a few moments studying the writing sample, looking particularly for any diminution in the size of the letters. I also look for any bunching and cramping of the script or evidence of any irregularity, faintness, or slight tremulousness on the upstrokes. Next, I draw an Archimedes screw (a spiral) and ask the patient to copy it, first with their writing hand, and then with their other hand, reassuring them that it will be a much harder task to complete with the non-writing hand.

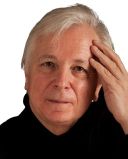

If the patient's handwriting has always been small then it can be difficult to detect the tell-tale "micrographia" of Parkinson’s disease, and abnormalities may be more clearly visualized in the spiral drawing. In patients with Parkinson’s disease, the Archimedes screw is smaller and with more tightly compressed turns. If, on the other hand, diagnosis is an isolated, indeterminate hand tremor which, in the elderly, commonly masquerades as Parkinson’s disease, the handwriting and spiral will be large, bold, and extremely shaky (Figure 1).

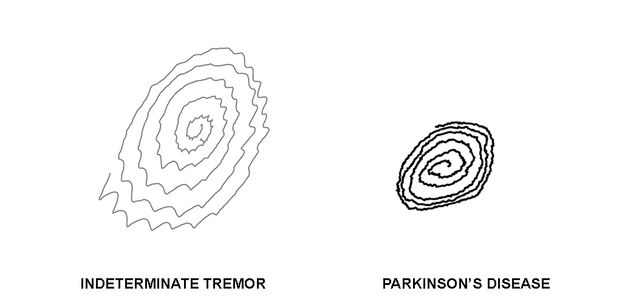

If I am still in doubt I may next ask the patient to draw a house with a door and windows and then examine the picture for the pathognomonic "floating door sign" of Parkinson’s disease (Figure 2).

People with Parkinson’s disease write slowly and tire quickly, forcing them to halt in mid-sentence and lift the pen from the page and start again This manoeuvre may lead to a brief temporary increase in the size of letters but the characteristic decrement recurs even more quickly and culminates with the end of the sentence tailing off in an illegible squiggle. If the patient is right-handed, the Parkinsonian script often slopes steeply upwards, while in left-handers it drifts down the page. Many people with Parkinson’s disease resort to printing each letter and discover that they can increase the size of their writing if they use lined paper as a visual cue.

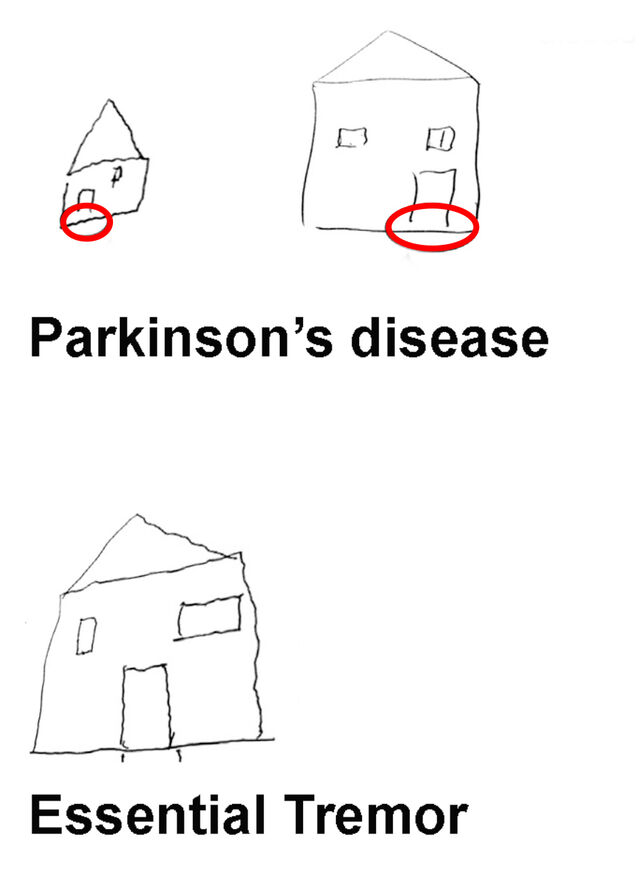

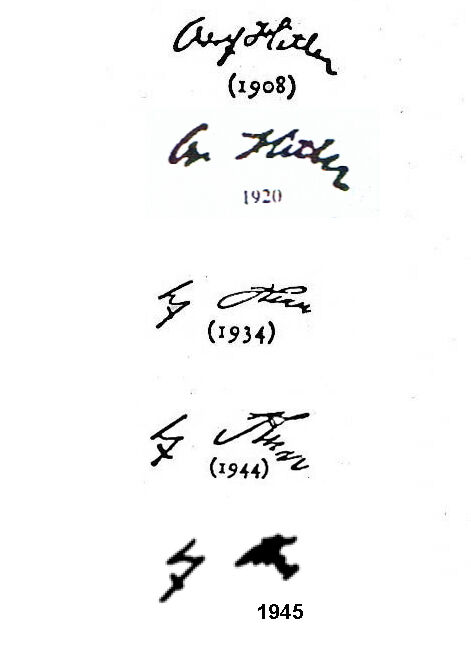

Serial monitoring of handwriting provides an index of disease progression and, if a patient can provide samples of handwriting going back many years before the start of their symptoms, it may be possible to retrospectively estimate when the first problems with finger dexterity occurred, as in these chronological signatures of Margaret Bourke White, the American photographer and first female war correspondent, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease when she was 49 but whose samples of handwriting suggested to her neurologist that the malady had been brewing for several years before that (Figure 3).

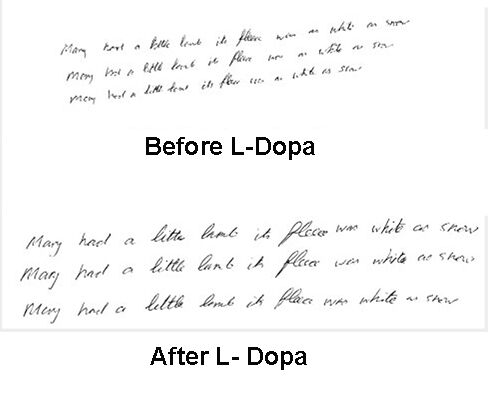

L-DOPA, a naturally occurring amino acid precursor of dopamine, is the treatment of choice for most people with Parkinson’s disease. It can markedly improve handwriting. and comparing a sample of script after treatment with one from before medication was started can be used to convince patients of the effectiveness of their treatment (Figure 4).

One of the pieces of evidence used to prove that the 60 volumes of Hitler diaries purchased for $4 million by the West German magazine Stern were fake was the fact that there was no detectable decrement in the size of written letters in the last entries. Hitler was known to suffer from Parkinson’s syndrome in the later years of his life and had a prominent tremor of one hand. Authenticated copies of his handwriting showed some of the changes characteristic of micrographia (Figure 5).

A diagnosis of Parkinson’s syndrome can be suspected sometimes by simply looking at a letter or postcard and does not need expensive and time-consuming digitizing tablet technology. The systematic physical examination involving 'the laying on of hands' remain an integral component of routine neurological practice and frequently leads to accurate localisation of the site of pathology beyond the resolution of neuroimaging.

References

McLennan JE, Nakano K, Tyler HR, Schwab RS. Micrographia in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci. 1972;15(2):141-52.

Doyle D. Adolf Hitler's medical care. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2005;35(1):75-82.