Pregnancy

Exercise During Pregnancy Aids Infant's Brain Development

Active mothers promote their own health and enhance their baby's brain function.

Posted November 12, 2013

If you remember Elvis Presley on The Ed Sullivan Show, you may also remember the advice doctors were giving pregnant women at the time: keep off your feet, sit and lie down as much as possible, take it easy like you never have before. Pregnancy in the 1950s was not a time for long walks on the beach.

If you remember the Beatles on that same show, then you remember when times changed, and prenatal exercise classes for expectant moms start to sprout like dandelions in May. What changed—and why?

The simple answer is that physicians learned through experience that active moms are healthier moms who have healthier babies. While no one was suggesting that pregnant women take up weightlifting, the advice became, "Keep doing whatever you regularly do…but if you are not exercising, now is a good time to start."

Today many pregnant women follow that advice, taking for granted that exercise is good. “While being sedentary increases the risks of suffering complications during pregnancy, being active can ease postpartum recovery, make pregnancy more comfortable, and reduce the risk of obesity in the children,” says Daniel Curnier of the University of Montreal.

But the benefits don't stop there. At the Neuroscience 2013 Congress in San Diego last weekend, researchers at the University of Montreal and its affiliated CHU Sainte-Justine children’s hospital reported the results of a randomized, controlled study on the effects of maternal exercise on a child's brain development.

The team randomly assigned pregnant women (at the beginning of the second trimester) to an exercise group or a sedentary group. Women in the exercise group performed at least 20 minutes of cardiovascular exercise three times per week at a moderate intensity, which should lead to at least a slight shortness of breath. Women in the sedentary group did not exercise.

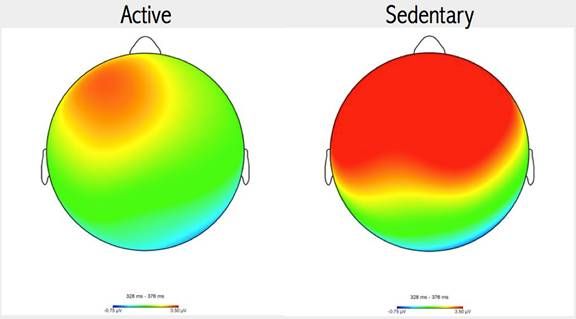

At 8 to 12 days after birth, the babies of those women had EEGs, which record electrical activity in the brain. “We used 124 soft electrodes placed on the infant's head and waited for the child to fall asleep on his or her mother's lap. We then measured auditory memory by means of the brain’s unconscious response to repeated and novel sounds,” says researcher Elise Labonté-LeMoyne.

The EEG tracings revealed that babies born to mothers who were physically active had a more mature cerebral activation, that is, their brains had developed more rapidly. “Our research indicates that exercise during pregnancy enhances the newborn child’s brain development. Basically it's the same benefits adults get from their own exercise,” says Dave Ellemberg, who led the study.

Brain activity is more localized in babies born to active mothers (left). The babies' brains are more mature and more efficient.

While similar results have emerged from animal studies, the Montreal team says theirs is the first randomized controlled trial in humans to objectively measure the impact of exercise during pregnancy on the newborn’s brain. The researchers are now evaluating the children’s cognitive, motor, and language development at one year of age to find out if differences persist.

"This is a wonderful motivational tool for pregnant women who need that extra push to exercise. They can give this boost to their baby's brain by doing as little as 20 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise three times a week (which can be as simple as walking in the third trimester)," says Labonté-LeMoyne.

About the Researchers

Elise Labonté -LeMoyne

Dave Ellemberg, Ph.D. and Daniel Curnier, Ph.D., are professors at the University of Montreal’s Department of Kinesiology. Elise Labonté -LeMoyne is a Ph.D. candidate in the same department. Ellemberg is also affiliated with the Centre hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine Research Centre. The University of Montreal is officially known as Université de Montréal.