Gender

Target Is Right on Target About the Use of Gender Labels

Why Target's decision to remove gender labels from toy aisles is good for kids

Posted August 14, 2015

I have been doing a lot of interviews this week after Target announced that they would remove their gender distinctions from toys and bedding. Basically, their decision simply means that toys and bedding will be organized the same way as they currently are, just without the labels “Girls Toys” and “Boys Toys.” The doll aisle won’t be labeled as just for girls and the pirate bedspread won’t be labeled as just for boys. When I read about this, I immediately applauded the decision (especially because I had JUST bought the pirate bedspread for my five year old daughter and was peeved by the signage).

I should have realized that backlash would soon follow, and it quickly did. The criticism boiled down to two main points. To paraphrase, one argument is that this decision will lead to chaos as confused grandmas aimlessly wander the aisles not knowing what to buy for their grandchildren (“My little Maggie likes My Little Pony, but the aisle isn’t labeled for girls. I don’t know where toys just for girls are.”). The second argument is that we are born as boys and girls and Target is trying to make all children transgendered. I was unaware that Target had this much power over our biology; I just thought they had good deals on towels.

The reality, however, is that Target’s decision is not coming out of nowhere. They are making a change that grassroots organizations have been championing for years. Let Toys Be Toys, for example, has campaigned for “toy and publishing industries to stop limiting children’s interests by promoting some toys and books as only suitable for girls, and others only for boys.” Play Unlimited is an organization whose slogan is “Every Toy for Everybody.” They push for No Gender December to urge parents to think about gender stereotypes when they buy their holiday presents.

The reason these organizations are pushing for stores and marketers to reduce their use of gender labels is because they have been listening to scientists. Science on how gender stereotypes develop in children has shown that Target’s decision is good for children. Why? First, toys are important for children.

Play is HOW children learn skills, learn about themselves, and learn about the world. All children need toys that encourage them to be active and develop hand-eye coordination (like balls), toys that help them practice spatial skills and learn basic physics (like construction and technology toys), toys that help them practice empathy and nurturance (like dolls), and toys that foster creativity (like arts and crafts). Unfortunately, these toys are segregated into boys’ aisles and girls’ aisles, and are explicitly labeled as such.

Many people assume that labeling and sorting by gender doesn’t really matter. The argument people have been making against Target’s decision is that boys and girls are naturally different, and boys inherently want Legos and action figures and girls inherently want dolls and tea sets. If this is true, then why would adding the label matter?

“Let Toys Be Toys” sums up it up well. They say,

“How toys are labelled and displayed affects consumers’ buying habits. Many people feel uncomfortable buying a boy a pink toy or a girl a toy labelled as ‘for boys’.

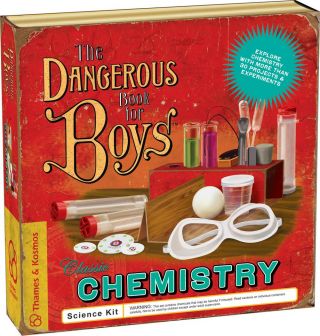

Other buyers may simply be unaware of the restricted choices they are offered. They may not notice that science kits and construction toys are missing from the “girls” section, or art & crafts and kitchen toys from the “boys”. If they’re never offered the chance, a child may never find out if they enjoy a certain toy or style of play.

And children are taking in these messages about what girls and boys are ‘supposed to like’. They are looking for patterns and social rules – they understand the gender rule ‘This is for boys and that is for girls,’ in the same way as other sorts of social rules, like ‘Don’t hit”. These rigid boundaries turn children away from their true preferences, and provide a fertile ground for bullying.”

This is indeed what children do. In fact, research has shown that the label of the toy – as either girls’ toy or boys’ toy– is actually more important than the toy itself. In multiple studies that have been replicated often, preschool children have been brought into a research lab and given a toy created by the researchers, one the children have never seen before. Some kids are told it is a toy that boys like to play with, and some are told it is something that girls like to play with. Boys who think they are playing with a boy toy think it is lots of fun. When they are told it is a girl toy, they say it is no fun and don’t want it. Girls do the same thing. They love it when it is labeled a girl toy, and dismiss it when it is labeled a boy toy. The toy never changed, just the label. It is not surprising, then, that girls make a beeline for the girls’ section of the toy store and boys to the boys’ section. It is often less about their interests and more about identifying with the “right” group.

It goes way beyond simply saying the “right” toy is more fun than the “wrong” toy. When children are given new toys and told they are either boy toys or girl toys, children explore the toy for their gender more carefully, spending more time learning about it and figuring it out. They touch it more, inspect it more, and ask more questions about it. Not surprisingly, they also remember more about those toys that were labeled for their group. Remember that this is preschoolers! This is not about boys being born to play with trucks and girls to play with dolls. This is about labeling trucks as boy toys and dolls as girl toys and children knowing which toy they are supposed to play with (and which toy to avoid like the plague). They then, naturally, develop an expertise in their own group’s toys. Before age 2, boys and girls like dolls to the same degree. It is only once boys learn about being boys does their interest in dolls plummet.

Knowing which is the “right” toy can even influence how good children are at playing with it. Raymond Montemayor, a psychology professor at the Ohio State University, brought six- to eight-year-old children into his lab. He told them about his new throwing game called Mr. Munchie (which was really just a Canadian toy unknown to US Midwestern kids). To score points, children throw as many plastic marbles as they can into a clown’s mouth in thirteen seconds. Some of the children were told the game was “for girls, like jacks.” Other children were told that the game was “for boys, like basketball.” Not only did children like the game better when it belonged to their group, they also performed better when it was for their group. Girls tossed more marbles into the clown when they were told it was a girl game than when they were told it was a boy game. Conversely, boys were more accurate when they thought it was a boy game rather than a girl game.

All of these studies tell us that children, before they start first grade, know they are boys or girls and know all sorts of “rules” about boys and girls. They know which toys boys and girls play with, how boys and girls are supposed to act, and what kinds of jobs boys and girls will grow up to have. More importantly, believing a toy or activity is for boys rather than girls will determine who plays with it, who learns about it, and who is better at it. The label alone is enough to drive kids’ behavior.

What we have learned is that labels matter! Not so much for adults, but for children. Labels point out that there are rules about who can play with what. These are rules that children enforce for themselves because boys want to be a good example of a boy and girls want to be a good example of a girl. The problem is that this limits the skills and abilities that children will develop. Every time a boy shies away from the doll aisle (an evitable consequence of labeling it for girls), he misses out on a chance to develop the nurturing and caretaking skills that will be helpful when he becomes a dad. Every time a girl shies away from construction toys (an evitable consequence of labeling it for boys), she misses out on practicing her spatial skills that will later be tested in advanced math classes. Labels drive these choices. If more stores followed the lead of Target, it would be an important step in kids becoming more well-rounded, more successful individuals.

To read more about how these issue affect children, read:

Parenting Beyond Pink or Blue: How to Raise Kids Free of Gender Stereotypes

For a great article, read this on A Mighty Girl website

To read the specific studies mentioned, see:

Bradbard, Marilyn R., and Richard C. Endsley. "The Effects of Sex-Typed Labeling on Preschool Children's Information-Seeking and Retention." Sex Roles 9 (1983): 247-260.

Montemayor, Raymond. "Children's Performance in a Game and Their Attraction to It as a Function of Sex-Typed Labels." Child Development (1974): 152-156.