Motivation

Purpose: What Drives All the Things We Do?

Have researchers overlooked which motives influence us most?

Posted April 5, 2018

What motivates us the most? Depending on who's defining it, motivation may refer to the reasons we do what we do, the process of finding those reasons, or the factors that cause us to act. Regardless of the definition, it is simply a word that allows us to talk about our needs, wants, desires, or drives to do things, but the word itself explains none of that. Saying that someone is intrinsically motivated to do something he or she inherently wants to do or extrinsically motivated to do something in order to get something else does not explain why the individual is so motivated in the first place.

Why do we do the things we do?

Sigmund Freud (1920/1955) viewed our most important motivations as instinctive.

- Life instincts: All the drives to do the things that keep us and our species alive. Viewing these as interrelated, he named the life instinct(s) eros for the Greek god of erotic love. As for why he thought of them as being collectively about sex instead of collectively about appetite, well, he was Sigmund Freud.

- Death instincts: Alfred Adler had suggested a death instinct as a counterpart to life instinct. Though Freud resisted the idea for some time, he eventually developed his own concept of death instincts to refer to motivations based on our awareness of our own mortality. Many sources incorrectly credit him for naming this thanatos for a Greek death god when, in fact, it was his colleague Wilhelm Stekel (1950) who later dubbed the death instinct(s) thanatos.

We spend all our time being alive and only a certain amount of it focused on death and destruction, so Freud continued to view the life instinct(s) as more important and most influential on our behavior and personality development. Sexual motivation may be parceled into different drives depending on individual goals, the most obvious being pleasure and procreation.

- Pleasure: People enjoy sex. Not everyone enjoys it in and of itself, whether because of sexual dysfunction, relationship issues, circumstances, or other concerns. Those who receive no intrinsic pleasure from sexual activity may nevertheless receive some form of extrinsic reward (such as practice for the future, the maintenance of relationship harmony, or dinner) and ultimately still do it to fulfill some pleasing purpose.

- Procreation: Of course, the reason sex is physically pleasurable is no doubt so that organisms will engage in sexual activity in order to reproduce. People, though, can choose to perform sex acts with the deliberate intention of trying to have a baby.

Sex drive seems to influence us in ways arguably unrelated to raising the odds that someone will have sex. Erotic influences appear in art, architecture, literature, humor, and perhaps every area of life. Those inclined to think like Freud might suggest that it is in everything whether we're conscious or it or not.

Existentialist psychologists (Frankl, 1946; May, 1960/1969), anthropologist Ernest Becker (1973), and adherents of terror management theory (Greenberg et al., 1986) echo some of what Freud talked about during his musings on possible death instincts: We learn that people die. We learn that we will die. We do many things to cope with this existential awareness.

- Stalling death.

- Making life meaningful.

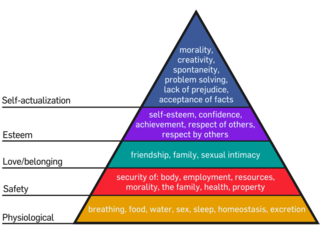

Building on the ideas espoused by Adler and others, humanistic psychology founder Abraham Maslow (1943, 1966, 1970) developed his famous, though inconsistently supported (Miner, 1984, model of a hierarchy of needs that he believed people would work their way through to advance from dwelling on the most basic physiologically-based needs to trying to reach our potential as human beings, self-actualization. The five-level pyramid depiction of Maslow's model is its best-known version, although three-level and seven-level variants are out there as well.

- Self- actualization.

- Self-esteem.

- Love and belongingness.

- Safety.

- Physiological needs.

As popularly conceived, Maslow's model does not directly examine the need for liberty, perhaps because he sided so heavily on the free will side of the age-old free will vs. determinism debate. Erich Fromm, though, believed that the pursuit for liberty is one of the most basic drives of all. He argued that the "basic human conflict" involves the often conflicting desires for freedom vs. security. From the time we're toddlers, we want to be allowed to do what we want and yet we also want to feel safe.

- Freedom.

- Security.

Henry Murray (1938) identified numerous psychological needs, three of which David McClelland (1961) felt exerted the greatest influence over what we do. These three dominant needs, he felt after reviewing the literature, comprise most human motivation.

- Affiliation: Connecting with others.

- Achievement: Overcoming obstacles, attaining lofty standards, rising to a challenge, and rivaling or surpassing others.

- Power: Controlling self, others, circumstances, or resources, more for the sake of wielding power itself than in order to achieve other goals.

Some might argue that all of these are, in one way or another, ultimately about survival. Where are the aesthetics? How does my sitting for a few minutes while listening to someone play the piano help me or my species survive? How does staring into a phone playing Panda Pop enable a person to manage the fear of death? And why do we watch so many cat videos?

In other words, are these grand theories of human motivation all missing some huge, important piece of what drives us to do the things we do?

Related Posts

- Hungry vs. Loyal: Ramsay's Hounds on the Hierarchy of Needs

- Freedom vs. Security in Marvel's Captain America: Civil War

- Freedom vs. Security in Z Nation's Zombie Apocalypse

- Fear Lessons in Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Doctor Who

- Doctor Who: "Listen" to Your Fear

- The Dark Knight Rises: What Motivates Bane?

- Naming Evil: Dark Triad, Tetrad, Malignant Narcissism

References

Frankl, V. (1946). Man's search for meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Freud, S. (1920/1955). Beyond the pleasure principle. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 18, pp. 7-64). London, UK: Hogarth.

Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R.F. Baumeister (ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189-212). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Maslow, A. H. (1966). The psychology of science. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). The farther reaches of human nature. New York, NY: Viking.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton: Van Nostrand.

Miner, J. B. (1984). The validity and usefulness of theories in an emerging organizational science. New York, NY: Human Sciences.

May, R. (1960/1969). Existential psychology (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Random House.

Murray, H.A. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stekel, W. (1950). The autobiography of Wilhelm Stekel: The story of a pioneer psychoanalyst. New York, NY: Liveright.