Attachment

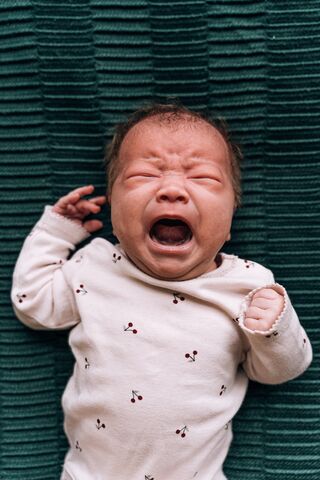

Is It OK to Let a Baby "Cry It Out"?

What it might mean for secure infant-parent attachment.

Posted May 30, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- "Crying it out" describes putting a baby in a safe space and leaving it alone for a while.

- Despite strong claims, only a few studies have been conducted on possible harmful outcomes.

- The argument that "crying it out" leads to long-term harm is not possible to affirm or refute.

Infant crying is the only means of communication between the baby and the parents, eliciting protective and caring parenting behaviour. But it can also be a source of parental stress, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, and depression if the crying is inconsolable. Thus, many parents turn to behavioural techniques to manage infant crying, which may include different forms of leaving their baby to "cry it out."

However, whether parents should leave their baby to "cry it out" has been debated by researchers, clinicians, and parents for a long time: Does "crying it out" cause long-lasting harm to the baby?

Before evaluating the research findings, let’s first consider what is meant by the term "crying it out."

What Does "Crying It Out" Mean?

"Crying it out" is an umbrella term used to refer to any method which involves putting the baby in a safe space such as a crib and leaving it alone for a while (Blunden, Thompson, & Dawson, 2011; Ramos & Youngclarke, 2006). This is based on the psychological concept of "extinction" in learning theory—unwanted behaviours (infant crying) are eliminated by removing the reward (parental responding).

There are different versions of crying extinction techniques, such as removing parental responses completely (unmodified extinction) or more gradually (gradual extinction) by increasing how long the baby is left to cry in small increments.

For parents who feel uncomfortable leaving their baby alone in a room to cry, there are other versions such as "camping out," in which parents stay in the same room with their baby but do not pick them up.

The unmodified extinction method is generally not advised and is very difficult to implement. Milder versions such as gradual extinction and camping out are used by many parents after four months of age.

Several studies showed that these techniques can help decrease the crying duration and night-waking, as well as parental stress, fatigue, and depression (Hall et al., 2015; Mindell et al., 2006).

Despite the benefits, "crying it out" sounds like a very harsh parenting approach, and it could be stressful to implement. Unsurprisingly, there are many claims about the potential harms of "crying it out," such as insecure infant-parent attachment, increased stress in babies, and long-lasting emotional problems.

These claims seem plausible from a theoretical point of view, considering the importance of sensitive parenting and secure infant-parent attachment in the development of emotional well-being. However, there are even unsubstantiated claims that it leads to brain damage (see Narvaez, 2011) that go well beyond what the research has shown so far.

Although the critical point of view on "crying it out" is understandable, it is important to first evaluate the evidence before drawing conclusions.

Is "Crying It Out" Harmful to the Formation of Secure Infant-Parent Attachment?

Attachment theory suggests that prompt parental responses to an infant’s needs are essential to forming a good quality relationship between the infant and the parent. Infant crying is considered a social behaviour that hardwires parents to respond to their infant and is thus seen as a precursor of secure attachment between the baby and the parents.

From an attachment theory point of view, if parents ignore their baby’s crying, this could harm the development of a secure relationship between them and their baby.

There was preliminary support for this claim from a small naturalistic study (Bell & Ainsworth, 1972). The researchers conducted home observations during each of the four quarters of the baby’s first year for approximately four hours per visit. They found that leaving the baby to "cry it out" increased the frequency and duration of crying (Bell & Ainsworth, 1972) and was associated with insecure infant-mother attachment at 12 months (Ainsworth et al., 1978).

However, these findings were criticized based on the small sample size of only 26 families and the simplistic analytical approach based on correlations without considering the possible influence of any other variables such as parental education level (Gewirtz & Boyd, 1977).

Subsequently, three replication studies were conducted: a study of 50 mother-infant dyads in a Dutch sample (van Ijzendoorn & Hubbard, 2000), our study of 178 mother-infant dyads in a British sample (Bilgin & Wolke, 2020), and a Canadian study of 137 mother-infant dyads (Giesbrecht et al., 2020).

None of those studies found any significant association between leaving an infant to "cry it out" and insecure infant-mother attachment, calling the generalisability of the Ainsworth findings into question. However, there are still few studies on this topic overall, and more longitudinal studies are needed.

Does "Crying It Out" Increase the Baby's Stress Levels?

In addition to insecure infant-parent attachment, it has been argued that leaving a baby to cry it out would increase the baby’s stress levels. This argument is based on the Middlemiss (2012) study, which investigated cortisol levels (a stress hormone) in 25 mothers and infants during an in-residence, hospital-based sleep training programme. During this five-day programme, parents did not respond to their baby’s nighttime crying.

There was no significant increase in infant cortisol levels during the first three days of the sleep training programme. However, the mothers’ cortisol levels decreased on the third day. The authors suggested that this revealed a problem with the "crying it out" technique because it resulted in asynchrony between the infant and the mother’s cortisol levels.

This finding was misinterpreted in the media, suggesting that "crying it out" causes stress for the babies. However, there was actually no influence on the baby’s stress levels; there were, however, reduced stress hormone levels for the mothers.

In addition to this misinterpretation, this study had limitations such as not reporting the initial cortisol levels and not reporting the findings beyond three days.

Is There Any Evidence of Harmful Outcomes Beyond Infancy?

Attachment theory suggests that infants will internalise early disruptive experiences with their caregivers and those experiences will have an enduring negative influence on their psychosocial functioning and emotional development throughout their lives (Fearon et al., 2010; Madigan et al., 2016). Thus, it is plausible that "crying it out" could have long-lasting negative influences on children’s emotional and behavioural development. However, research on the long-term outcomes of "crying it out" is very limited.

Only one study has investigated the outcomes beyond infancy so far. In that randomised control trial (Price et al. 2012), gradually increasing the waiting time before responding to infant crying was associated with a decrease in crying durations and night-waking while having no ill effects on the baby’s emotional and behavioural development and stress levels (i.e., diurnal cortisol) five years later.

This study seems to suggest there are no long-lasting effects on the emotional and behavioural development of the baby. However, it is important to note that the study had several methodological problems, such as a high parental rejection rate for the treatment group.

Moreover, parents in the treatment group were aware of the treatment (i.e., parents were not blinded). This might influence parents’ behaviour during the intervention, as well as their responses to outcome measures such as the measurement of emotional and behavioural problems of their children.

To Conclude

Despite strong claims, only a limited number of studies were conducted on the possible harmful outcomes of leaving a baby to "cry it out." Given that these studies had several methodological problems, the argument that "crying it out" leads to long-term harm is not possible to affirm or refute yet.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Lopolo/Shutterstock

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Oxford, England: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bell, S. M., & Ainsworth, M. D. (1972). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Development, 43(4), 1171-1190.

Bilgin, A., & Wolke, D. (2020). Parental use of 'cry it out' in infants: no adverse effects on attachment and behavioural development at 18 months. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(11), 1184-1193.

Blunden, S. L., Thompson, K. R., & Dawson, D. (2011). Behavioural sleep treatments and night time crying in infants: challenging the status quo. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 15(5), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2010.11.002

Fearon, R. P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Lapsley, A. M., & Roisman, G. I. (2010). The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children's externalizing behavior: a meta-analytic study. Child Development, 81(2), 435-456.

Gewirtz, J.L., & Boyd, E.F. (1977). Does maternal responding imply reduced infant crying? A critique of the 1972 Bell and Ainsworth report. Child Development, 48, 1200–1207.

Giesbrecht, G. F., Letourneau, N., Campbell, T., Hart, M., Thomas, J. C., & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. (2020). Parental Use of "Cry Out" in a Community Sample During the First Year of Infant Life. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 41(5), 379-387.

Hall, W. A., Hutton, E., Brant, R. F., Collet, J. P., Gregg, K., Saunders, R., Ipsiroglu, O., Gafni, A., Triolet, K., Tse, L., Bhagat, R., & Wooldridge, J. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of an intervention for infants' behavioral sleep problems. BMC Pediatrics, 15, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0492-7

Madigan, S., Brumariu, L. E., Villani, V., Atkinson, L., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2016). Representational and questionnaire measures of attachment: A meta-analysis of relations to child internalizing and externalizing problems. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 367-399.

Middlemiss, W., Granger, D. A., Goldberg, W. A., & Nathans, L. (2012). Asynchrony of mother-infant hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity following extinction of infant crying responses induced during the transition to sleep. Early Human Development, 88(4), 227-232.

Mindell, J. A., Kuhn, B., Lewin, D. S., Meltzer, L. J., & Sadeh, A. (2006). Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep, 29(10), 1263-76.

Narvaez, D.F. (2011). Dangers of “Crying It Out”. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/moral-landscapes/201112/dangers…

Price, A. M., Wake, M., Ukoumunne, O. C., & Hiscock, H. (2012). Five-year follow-up of harms and benefits of behavioral infant sleep intervention: randomized trial. Pediatrics, 130(4), 643-651.

Ramos, K. D., & Youngclarke, D. M. (2006). Parenting advice books about child sleep: cosleeping and crying it out. Sleep, 29(12), 1616-1623.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Hubbard, F. O. (2000). Are infant crying and maternal responsiveness during the first year related to infant-mother attachment at 15 months? Attachment & Human Development, 2(3), 371-391.