Education

Language, Learning and the Essence of Experience

How experience teaches us in ways we don’t expect

Posted June 23, 2013

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Unlike what some may expect, it wasn’t the writing that had me worried. Although it can sometimes take me awhile to get started, when I do I can be quite prolific (In school, I once cheekily entitled a writing assignment “Look, I Got Carried Away and Ruined About Seventeen Perfectly Good Pieces of Paper.” Fortunately for me, the teacher had a good sense of humor.).

No, I was more worried about other things. Finding the time to do the pre-work necessary. Figuring out the logistics of interviewing when telephones and notetaking are difficult for me, and how to explain the accommodations I needed as a result of those difficulties to others. Adapting my organizational techniques to function a new context, within a tight time frame. Imagine my surprise when I sat down to find that one of my first major challenge was linguistic after all.

When it comes to communicating with others, I’ve always thought of writing as my “native” language. It’s always been my fallback when verbal language failed me, and because it usually functioned in this context, I’d come to think of it as relatively “unimpaired” in comparison. But as I sat down to write, I discovered something that surprised me.

On a strict deadline, I sat down to write, and nothing came. Was this writer’s block? Well, it wasn’t as if I didn’t know what I wanted to write...as happens with me, my mind was going all day, every day. I compose in the shower, as I dress and as I travel to work. Any time my mind has a free moment, it’s working. Typically, when I sit down to write, all I have to do is transcribe the pieces already formed in my head. So, why couldn’t I do it?

As I sat there, I attempted to will my fingers to move to form the words bursting forth from my brain – but nothing happened. Maybe writing wasn’t the cure-all for communication that I thought it was. What was happening was exactly what happens when I lose speech…when the thoughts and language fully form in my head, my mouth simply won’t cooperate. But, in this case, the body parts that refused to comply were not my tongue and mouth, but my fingers. How odd.

Then I noticed something. As I sat there, I realized that my mouth was moving. Softly, I was reciting the words that I wanted to be able to put on paper. The words I was trying to type. This was an interesting development, one which forced me to re-assess my understanding of how my own linguistic idiosyncrasies worked. Suddenly my tendencies were flipped – normally I could write, when I couldn’t talk. Now I was finding that I could talk, when I couldn’t write. Interesting.

I had believed that I was always able to write, while verbal communication could sometimes be spotty…but now I was wondering if maybe it wasn’t quite so simple. Was it possible that, just as some adults on the spectrum talk about being mono-channel when processing input (sensory and otherwise), that the same could be true in terms of output as well? Could it be that there were times when one channel subsumed the other? If so, why had I not noticed it before? Was it because I was expected to speak more often than to write?

Whatever the reason, I had to find a solution – and quickly. I couldn’t afford to miss my first deadline as an author. If I could speak the sentences that were there in my head, then the solution seemed easy. All I needed was a way to transcribe those thoughts and, well, they have software that does that today, don’t they?

I made a hasty trip out to my local office supplies store, and bought the best known software of this type – Dragon Naturally Speaking. I installed it, and was on my way. The draft of that chapter shaped up quickly. When it was done, I asked my husband to give it a read, as I often do. As he read the rough draft, he noticed something. “You’ve got a lot of repeated words in here…” he said. When I re-read the draft, I saw he was right. What was that about?

Some of it was easy enough for me to explain – one of my verbal “glitches” tends to be repetition. When speech troubles come to the fore, I can begin to sound like a skipping record. “And….and….and….” It’s as if a mountain has appeared between my brain and my mouth, and repetition builds the momentum that will eventually get me over that mountain. But I had no idea, until I saw it documented in black and white, how frequently such repetition creeps into my speech without my knowing it.

I began to pay attention to the process I was going through as I wrote – watching for the repetition to happen real-time. As I did, I noticed another dynamic I hadn’t previously noticed. When I speak, there are many times that my speech will “go south” mid-sentence. What I mean to say just doesn’t form right. What comes out may be a substitute word or phrase, or something that makes little sense at all. Sometimes, I’ll catch this occurring midstream, and stop mid-word. Other times, a stutter will split a word, causing additional words to be transcribed that I didn’t mean to say (with sometimes scary results).

In most of these instances, I would catch the glitch in progress, then go back to fix it. The problem came when the issue came mid-phrase. I’d go back to try to fill in the fouled up part, only to find that I couldn’t speak just part of a phrase. Time and time again, I’d repeat the phrase in its entirety, thus leaving a repeated word. The only way for me to recover from such a “glitch” was to start the phrase entirely from scratch.

This also taught me a great deal about how I process language. It’s been written that “The child with autism processes information as a whole ‘chunk’ without processing the individual words that comprise the utterance.” It would seem that as an autistic adult, I still do process language in chunks, rather than individual words. I wondered how common it was among other autistic adults, so I posed the question to my followers on Facebook. The conversation was lively, and interesting – and it seems that I’m not alone in the tendency. We are a chunky bunch!

I set out to write a book to help others learn how to navigate through the challenges that having autism can bring in a world that doesn’t understand those differences. I’ve spend more than a decade now learning whatever I can about autism: reading books and research papers, watching documentaries and seminars, as well as talking to experts and others on the spectrum. Yet, the process of writing a book to help others taught me a great deal about how autism affects me in a way that those studies didn’t. There’s something poetic in that.

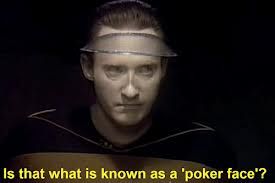

Thinking of this, I’m reminded of a particular conversation depicted in one of my favorite episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation, The Measure of a Man. In the episode, the android character, Data, is told he will be disassembled for study – by a scientist whom he feels does not have the knowledge and skills to do so safely. He is forced to articulate his objections to the procedure, which results in a discussion about the nature of learning, and “the essence of experience.”

Discussing the differences between rote learning and experience, he uses poker as an example: “I had read and absorbed every treatise and textbook upon the subject, and found myself well prepared for the experience. Yet, when I finally played poker, I discovered that the reality bore little resemblance to the rules.” When I first watched this episode, years ago, this particularly resonated with me – and years later, I still find it proves true.

Study is important, but it is no substitute for experience.

For updates you can follow me on Facebook or Twitter. Feedback? E-mail me.

My first book, Living Independently on the Autism Spectrum, is currently available at most major retailers, including Books-A-Million, Chapters/Indigo (Canada), Barnes and Noble, and Amazon.

To read what others have to say about the book, visit my web site: www.lynnesoraya.com.