Health

Using Art to 'Touch' Someone in a Juvenile Detention Center

Using body art to help a teen in a detention facility reconnect and heal

Posted March 12, 2015

This post’s guest blogger, art therapist Elise Lunsford, is an innovative and thought-provoking clinician working with very difficult clients. A graduate from the George Washington Art Therapy program, she serves as a full-time art therapist for a mental health community center in the upper-south region of the United States; one of her clients ended up in a detention facility where she was able to continue her work.

I first talked with Elise Lunsford back in August, when she contacted me with some questions regarding our shared interests. I soon came to realize how important her work was with the troubled adolescents; of particular interest was the work she had done with the one who was detained in the juvenile center. The following post underscores how important it is to sometimes take chances, and exercise unique and creative approaches to reach the unreachable. In forensic settings, clinicians are often warned not to touch the inmates. Ms. Lunsford reminds us that sometimes it is important for us to reach out and touch those who we would otherwise hesitate to touch—and we do so through the art.

Art as a Candle in the Dark: Trauma Art Therapy and Body Art in a Juvenile Detention Setting.

Elise Lunsford ATR-BC, LAC

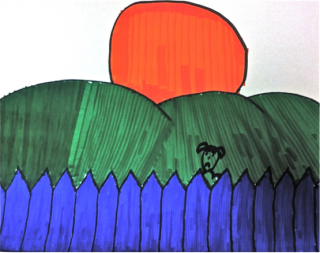

Zach is upset and feels guilty and evil; his left hand is cuffed to a bench. He reaches over, with his lower lip tucked in, demonstrating concentration, and picks out a black chalk pastel with his free hand. He is trying to complete his artwork one-handed, though he's having trouble with the paper. I help keep his paper steady. He is drawing his “safe place”.

This is my first time at the facility. Detention staff members do not know me and are concerned that Zach may try to attack me or flee, so he remains manacled. The staff eventually learned that I provided intensive therapy to Zach over the past 5 months before he was arrested. I had worked with him alone, in the same room, with the door cracked open, twice a week. He trusts, processes, expresses, and learns to cope. In sessions, he processes and explores feelings about his behavioral issues. He has never been inappropriate or aggressive in session.

As staff feel more confident in our rapport, the sessions moved into the social worker’s office. There, in a more private location, he is uncuffed.

Zach’s story is heart breaking, but unfortunately, common. He is a 17-year-old Haitian American, in foster care for several years. Caretakers used crack cocaine, neglecting and physically abusing Zach. His father was absent; his mother had a criminal background for violence. She was emotionally, physically, and sexually abusive. Zach took care of his developmentally delayed younger sister. By the time I began working with him, he has been moved to various placements over 25 times and became involved with gangs.

His discharge papers from all of his facilities included phrases like, “treatment failure….no progress…not appropriate for setting” etc. Zach has had multiple competency evaluations with mixed results. It is possible that he did not take his medication the day he was arrested after he ran away from staff. It seems family members, schools, churches, community programs, state and government programs, therapists and teachers had not been able to help Zach. No one did.

In addition to a long trauma history, he’s received countless diagnoses including learning disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and behavioral disorders.

Zach’s detention lasted 11 months. He was initially, high-risk, chronically suicidal and engaged in daily self-mutilation. He was verbally aggressive, frequently physically aggressive, sometimes dissociating and hallucinating. Zach carved designs into his hands and forearms with sharp objects. Often, Zach was restricted from academic or group services for his behaviors. Zach’s behavioral issues affected the entire facility, including disrupting the daily schedule.

Zach was emotionally delayed and struggled with abstract thinking, empathy, reality testing, impaired judgment, distorted cognitions, paranoid thinking, difficulty with planning, multi-step processes and critical thinking. To help him develop these skills, art therapy was used. Trauma-informed art therapy, art psychotherapy, positive art therapy, and TFCBT with an attachment-informed approach were used.

He used a wide variety of media. He was never left alone with the materials, and sometimes I needed to count materials before and after he used them. Facility administrators prescreened the materials used. Although Zach often snuck sharps into his room to self-harm, he never used art therapy supplies to do so.

I worked with him for 16 months, 5 months before he was arrested and his 11-month detention stay. I am not naive. He will likely need ongoing and long-term therapy and medication management. He may need long-term supervision either in a secure facility or with 24/7 supervision. But he has made progress.

Zach’s dissociative symptoms, regressive behaviors, and hallucinations went away. He improved his internal locus of control, he was no longer suicidal, he didn’t disrupt the facility, self-harming became rare, and he was more compliant with medication. Social workers reported that he learned restraint and preventative coping skills.

Surprisingly, he is incredibly resilient. He was charismatic, had a contagious smile and laugh, loved learning new things, played basketball and worked out with his P.E. teacher and detention staff. The staff I spoke with seemed to care for him deeply. They knew his history; although he was seen as “difficult”, they empathized with him.

Zach was doodling on his hand, and asked for technical assistance, as he wanted to draw a more complex image, but felt inadequate. I scooted closer and began drawing the image he needed help with on his arm—body art with Zach began. This technique developed organically in session. I realized later that some staff had concerns with the technique. It was important for me to meet with the facility supervisors to discuss the reasons for using body art and work collaboratively within the facility to provide treatment. Later, I provided staff with mental health literature. After that, staff accepted Zach’s mental health issues and his therapy.

I learned that Zach was isolated from other residents and was not allowed to see them as he was being charged as an adult. Staff also had a "no contact" policy. Despite this, body art became an means to provide positive touch and safe intimacy for the client. I saw the client’s needs and became the “artist’s third hand.” In general, body art was a way to decrease the psychological negative effects of an isolating environment.

According to Chillot, there is developing research on the benefits of positive touch, from rapport building, bonding and attachment (2013). Touch has the ability to make chemical and physical changes in the body, decreasing heart rate and stress while increasing oxytocin levels (National Public Radio, 2010). These are just a few of the studies on the benefits of touch.

“Body art” became a focus. In some sessions, we used body art during the entire period, with him processing issues as we drew. Zach would title his pieces and tattoos, which were photographed and kept as part of his clinical record. While I sketched the basic lines, he dictated to me: color, angles, size, shapes, line quality, and composition. I encourage him to come up with an inspirational phrase or coping skill for the day.

Perhaps what he needed most was a strong bond with a supportive parent. The trauma therapy and staff became his support—it might be a long time before he sees his family again. Zach told me that he has spent more time with me than he ever had with his family.

The services he received seem to have helped him improve his mental health. The structure, safety, and consistency helped him feel safe. Staff maintained the understanding that they were there to promote rehabilitation, not punishment. The director personally visited Zach after several sessions and discussed his body art and therapy homework.

Zach often held his hand or arm outside of the shower so he could keep the images intact until the following session. He looked at the images multiple times a day, long after I am gone. The benefits of the results of these sessions extended long after they ended. He may not have been able to have pictures of his sisters or keep his artwork in his room, but he could look and see his sister’s name we drew on him. Therapy literally left a physical mark on him.

His last placement change was to an adult facility, after he turned 18. Unfortunately, mental health services were not allowed without a court order.

During Zach's final art therapy session, he reflected on: [statements are in his words, including the misspellings and poor grammar]:

On therapy

“Therapy is good for everybody because it improve your skills and your self and your ever day life skills”

On art

“Art makes me feel special in side my heart because I’m gaining more skills that I thought I could never [sic] do in this life”

On body art

“Body Art has been around since the caveman days and so has Art (.) People uses art to releave their frustration, pain, and anxiety in so many ways possibly. Body Art and even just regular Art has helped me improve”

This case sheds light on the potential benefits of body art interventions, and how it can be used with isolated and disconnected clients. Zach replaced self-mutilation with these colorful designs. Greater attention and future research for body art interventions seems warranted.

Personal reflection:

I hope there will emerge continued changes within the legal and criminal court systems. I believe increasing mental health and trauma education, and training for first responders, legal professionals, and lawmakers will be vital for a progressive future.

Working full-time as an art therapist within the foster care system can be overwhelming. Friends and family often say to me “I don’t know how you do it everyday.” I am fortunate to work within a close-knit and supportive program. Our team members know that we can lean on each other when needed. I feel fortunate to have multiple supervisors for clinical supervision or simply to process a hard day. In addition, I have my fiancé, family and friends there for me everyday. Finding balance is key.

References:

Trudeau, M. (2010, September 20). Human connections start with a friendly touch. National Public Radio. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=128795325

Chillot, R. (2013, March 11). The power of touch. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/201302/the-power-touch