Happiness

The Puzzling Relationship Between Pet-Keeping and Happiness

The hedonic treadmill explains why pets don't make people happier.

Posted December 22, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- The $100 billion pet products industry promotes the idea that getting a pet makes people happier.

- Yet, more than a dozen studies have found that pet owners are not any happier than people who do not live with a companion animal.

- A psychological process called hedonic adaptation explains why pet-keeping is usually not associated with an increase in overall happiness.

- New research, however, has found that playing and interacting with pets does result in temporary increases in the happiness of their owners.

A recent headline in The Atlantic magazine asked “Which Pet Will Make You Happiest?” This question assumes that pet owners are happier than non-owners. Most pet lovers (including me) are convinced that our companion animals improve our quality of life. But what have researchers discovered about the relationship between pet ownership and happiness? I recently took a deep dive into this body of research. What I found was eye-opening.

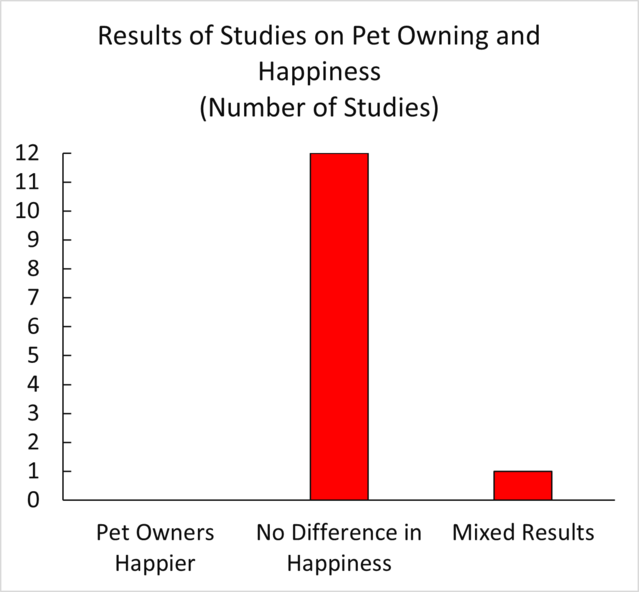

I tracked down the 13 studies from researchers in five countries that compared the happiness levels of pet owners and non-owners. (The studies and their results are described at the end of this post.) Contrary to what I expected and the claims of the pet products industry, not a single study found that, as a group, pet owners, were any happier than that non-pet owners. (One of the studies found that having a pet was associated with more happiness in rich women but lower happiness in poor women.)

Pets, Happiness, and the Hedonic Treadmill

The marketing departments of the pet products industry frequently state that researchers have consistently found that pet ownership is associated with better mental health and psychological well-being. (See, for example, Pet Effect ad campaign.) This claim, however, is simply not true. University of Tennessee investigators recently conducted the most extensive review of research on the impact of pets on psychological well-being. They reported that there was “a clear association of pet ownership and positive mental health” in only 17 of 54 studies. And I found that only 6 of 21 studies reported that pet owners were less lonely (here) and only 5 of 30 studies found reported they were less depressed (here).

The results of research on the impact of owning a pet on general happiness are even starker—none of the studies found that getting a pet will make the average owner happier. This was true of studies of pet owners in the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Mexico, Japan, and Croatia. What could explain the counterintuitive but consistent finding that pet owners are no happier than people without pets?

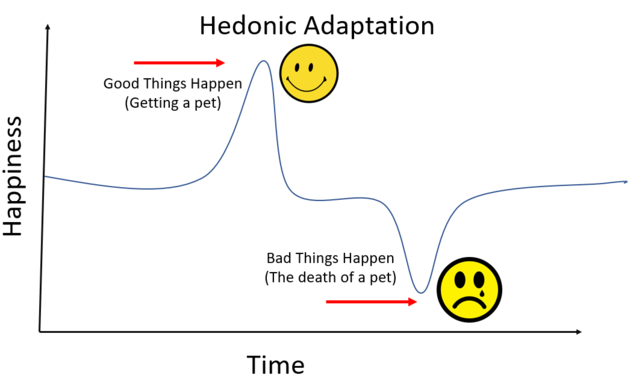

In her book, The Happy Dog, the University of Liverpool anthrozoologist Carri Westgarth suggests that a phenomenon called hedonic adaptation (also called, the hedonic treadmill) may be to blame. Hedonic adaptation is the tendency for humans to return to a stable baseline level after they experience either a major positive or negative event. That’s why the happiness you get from, say, buying a new guitar, or in the case of college professors—getting tenure, wears off, usually surprisingly quickly. Dr. Westgarth thinks the same thing applies to getting a pet. After the initial buzz you get from your new kitten or rescue dog, your life gradually goes back to normal. The upside of hedonic adaptation is that happiness levels tend to return to normal after bad things happen, for example, when your pet dies.

I think she is right. You need a general psychological process that is a fundamental aspect of human nature to explain why pet-keeping appears to be unrelated to subjective happiness across and within cultures. Hedonic adaptation would seem to fit the bill.

Some of the Time, Pets Do Make Us Happier

I certainly feel happy when Tilly decides to jump on my lap so I can scratch behind her ears while we watch TV in the evening. And Dr. Westgarth and her colleagues reported that increased happiness was a major motivation for taking dogs for a walk. That's why I was genuinely surprised that a large body of research has found that pets have little if any impact on their owners' overall levels of happiness.

Why is there a mismatch between the personal experiences of pet lovers and the findings of over a dozen empirical studies? A 2021 study based on data from the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a possible answer. The Bureau regularly assesses how Americans spend their day via an instrument called the American Time Use Survey (ATUS). Charlene Kalenkoski and Thomas Korankye obtained ATUS data on roughly 13,000 individuals over the age of 50. On a scale of 0 to 6, the participants were asked about their level of happiness when engaging in daily activities ranging from mowing their lawns and doing the laundry to brushing their teeth. Some of these activities involved pets, for example, brushing dogs, visiting an animal shelter, and feeding aquarium fish. In their analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics data, Kalenkoski and Korankye found that Americans are, on average, happier when playing and interacting with pets than when they are engaged in other activities on the same day.

This makes sense. I’m suggesting that playing a round of Frisbee with your dog produces a burst of neurochemicals like dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphin in your brain that are associated with good feelings. However, this jolt of pet-induced happiness is transient, and over the long haul, the hedonic treadmill exerts itself and, as the Beatles said, gets you back to where you once belonged.

The Studies on Pet-Keeping and Happiness

Here are the 13 studies and their results.

- In the most recent study, (December 2021) the anthrozoologist Francois Martin and his colleagues compared levels of depression, anxiety, and happiness among 768 dog owners matched with individuals who wanted a dog but did not have one. Even considering differences in social support, there were no differences between the owners and non-owners in happiness scale scores.

- In a 1998 paper, Australian researchers reported there were no differences in happiness scores of elderly men and women who lived with companion animals compared with people who did not.

- A 2016 study of 263 American adults found pet owners were no happier than non-owners.

- A 2020 study found that acquiring a pet in the previous year had no meaningful impact on the happiness of 879 Croatian adults.

- In a 2011 study, the social psychologist Allen McConnell of Miami University administered a four-item “subjective happiness” scale to 217 American adults. He found that owning a pet had no impact on their happiness scale scores.

- A 2020 study of older adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging found that currently living with a pet was unrelated to happiness.

- In a 2014 paper, Mexican researchers studied the health and psychological well-being between 377 Mexican dog owners and 225 non-owners. Dog owners were not any happier than those without a canine companion.

- The same Mexican research team subsequently investigated how the quality of the relationships between 483 dog owners and their pets affected perceived stress and happiness. They found that the quality of dog-owner relationships did not affect subjective happiness.

- In a 2009 study, Kathryn Gerlach analyzed data on happiness from a representative sample of 2,393 Japanese adults. She found that Japanese pet owners were no more likely to be happy than non-pet owners.

- In 2015, LaTrobe University researchers found no differences in subjective happiness between older Australian pet owners and non-owners.

- A 2020 analysis of data gathered as part of the General Social Survey in the United States reported that exactly 31% of pet owners and non-owners reported they were “very happy,” and about 15% of both groups indicated they were “not too happy.”

- Based on a large national sample from the British Household Panel Survey (over 10,000 participants), in 2007 British researchers found no relationship between pet ownership and “subjective general happiness.”

- In a 1983 report in the journal Research on Aging, researchers found no differences in happiness between 1,073 older female pet owners and non-owners. (However, among wealthy women, pet ownership was associated with greater happiness, but living with a pet was associated with lower happiness.)

References

Kalenkoski, C. M., & Korankye. T. (2021) Enriching lives: how spending time with pets is related to the experiential well-being of older Americans. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 1-22.

Scoresby, K. J., Strand, E. B., Ng, Z., Brown, K. C., Stilz, C. R., Strobel, K., ... & Souza, M. (2021). Pet Ownership and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Veterinary Sciences, 8(12), 332.

Martin, F., Bachert, K. E., Snow, L., Tu, H. W., Belahbib, J., & Lyn, S. A. (2021). Depression, anxiety, and happiness in dog owners and potential dog owners during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. PLOS ONE, 16(12), e0260676.