Animal Behavior

A Surprising Way to Fight Invasive Species

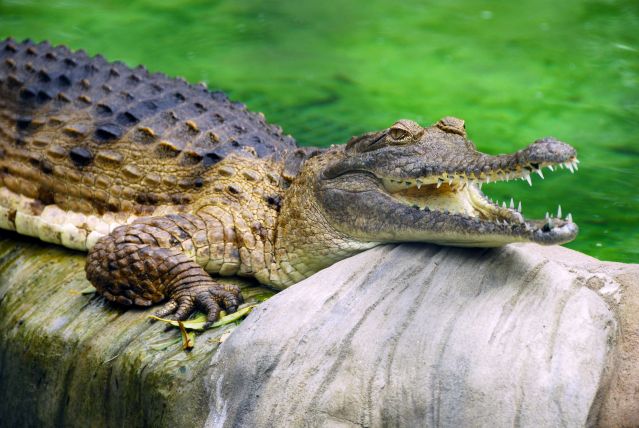

Teaching crocs with tainted toads: How food poisoning can help protect at-risk species.

Posted August 19, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- An Australian team used taste aversion to teach freshwater crocodiles to avoid toxic, invasive cane toads.

- Crocodiles developed aversions after encounters with cane toad baits designed to induce nausea but not kill.

- Crocodiles generalized this aversion to live, wild cane toads, and crocodile mortality was greatly reduced.

- Behavioral interventions targeting native predators may be an effective tool for invasive species management.

To protect freshwater crocodiles from deadly invasive cane toads, scientists at Macquarie University collaborated with Bunuba Indigenous rangers and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) in Western Australia. The team came up with a strategy that proved successful: They taught wild crocodiles to associate cane toads with a bout of food poisoning.

An Ongoing, Deadly Invasion

Cane toads were introduced into Australia in 1935 to serve as pest control for the sugarcane industry. That original purpose didn’t work out, but the toads have thrived and spread.

This has been disastrous for Australia’s native predators, which are highly susceptible to the cane toad’s toxins. Populations of predators such as monitor lizards, snakes, quolls (a carnivorous marsupial), and freshwater crocodiles have been decimated following the arrival of cane toads. These species are ecologically significant as well as culturally important to First Nations communities, including the Bunuba people of central Kimberley.

“We are seeing these large, distressing declines in our native predators behind the toad invasion frontline,” says Georgia Ward-Fear, a wildlife biologist at Macquarie University. “And they are still invading westwards at a rate of about 50 km (31 miles) a year.

“Nothing we have done to date has decreased their numbers, or slowed their invasion, or mitigated their impact on any meaningful scale.”

To facilitate coexistence with the toxic toads, Ward-Fear and colleagues have begun to work directly with the native predators themselves, using the premise of conditioned taste aversion.

Taste aversion is an innate behavioral mechanism that most, if not all, animals possess that prevents them from re-ingesting toxic foods in their environment. Essentially, it’s food poisoning.

“Even though these predators may have the ability to learn, they don’t have the opportunity, because every toad they engage with kills them,” says Ward-Fear. “We thought if we could teach freshwater crocodiles to avoid cane toads before the toads arrive in the environment, by exposing them to smaller, non-lethal doses of a toxin, then they might learn and then generalize that aversion to the cane toad invaders when they arrived.”

Taste Tests

Ward-Fear, together with colleagues at Macquarie University, local Bunuba rangers, and DBCA staff, worked with crocodile populations across four large gorge systems in the Kimberley region of northwestern Australia, as the cane toad invasion moved through the area in 2019-2022.

“The Bunuba rangers directed the strategy in a lot of ways based on their traditional ecological knowledge of the land and these animals,” says Ward-Fear. “I brought the Western science and DBCA provided the people power and the capacity to conduct this research.

“It’s been an effective collaboration, and I think that it should be the model going forward in conservation science—including the most pertinent stakeholders and scientists working with management agencies from the start.”

The team created cane toad baits by removing the toxic parts of the toads and injecting the carcasses with lithium chloride, a nausea-inducing chemical. They set up hundreds of bait stations over riverbanks, monitoring them via remote cameras and canoe surveys.

At first, crocodiles took toad baits and control baits (untreated chickens) equally. But within just five days, they had learned to avoid the toads, while still eating the chickens. The crocodiles had developed a taste aversion. Now would they transfer it to wild cane toads?

The arrival of cane toads into a new area is typically followed by mass mortality events—large numbers of freshwater crocodiles dying in a very short period. But in the gorges that Ward-Fear and colleagues baited, there were no mass mortality events after cane toads arrived. It appeared that the crocodiles had learned to avoid the invaders.

Conservation Success

Finally, the team tested the baited toads in a gorge system behind the invasion frontline. The crocodiles in this area had been experiencing mass mortality events since cane toads arrived two years earlier. Introducing baited toads into this environment essentially halted the mass mortality events, and the crocodile mortality rate declined by 95 percent.

The team has continued to monitor the sites, and Ward-Fear says they have not seen any cane toad-related crocodile deaths in those systems following the taste aversion training. Though the crocodiles seem to remember and avoid cane toads for some time, the research team recommends further taste aversion training in future years to instill the lesson in younger crocodiles.

In a previous study, Ward-Fear and colleagues demonstrated the use of conditioned taste aversion to protect another native predator, the yellow monitor lizard, from cane toads. Although the two species’ hunting ecologies necessitated different training strategies (live baby cane toads for the monitor lizards, for example), the results were the same: After the training, predators avoided cane toads, and mass mortality events ceased.

“These are the first long-term, large-scale programs applying taste aversion in the wild with reptilian predators, and the outcomes have been highly successful,” says Ward-Fear. “In both cases, we show that taste aversion can mitigate the impact of cane toads on wild predator populations, which is huge.”

References

Ward-Fear G, Bruny M, the Bunba Rangers, Forward C, Cooksey I, and Shine R. 2024. Taste aversion training can educate free-ranging crocodiles against toxic invaders. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 291: 20232507. Doi: 10.1098/rspb.2023.2507.