Sex

Queer Ducks and the Natural World of Animal Sexuality

A timely new young adult book covers queer behavior among diverse nonhumans.

Posted July 5, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- The idea that same-sex sexual behavior is "unnatural" is fueled by an overly narrow view of natural selection.

- A recent study estimates the number of animal species with confirmed substantial same-sex sexual behaviors to be 1,500+.

- Sex has benefits outside of procreation; whether heterosexual or homosexual, sex produces oxytocin, known as the “bonding hormone.”

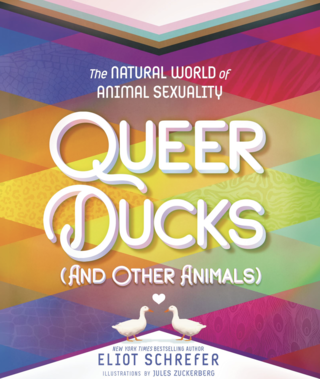

Bestselling author Eliot Schrefer's new book, Queer Ducks (and Other Animals): The Natural World of Animal Sexuality is a winner in many different ways. Among the numerous accolades for this young adult book focusing on the diversity of naturally occurring same-sex sexual behavior among nonhuman animals (animals) we read, "A thoughtful, thought-provoking, and incredibly fun study of queerness across the animal kingdom . . . it will help queer kids feel less alone as it highlights the filtered lens through which the animal kingdom has for too long been presented." (Kirkus Reviews)

I'm thrilled Eliot could take the time to answer a few questions about his riveting new book. Here's what he had to say.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write Queer Ducks (and Other Animals)?

Eliot Schrefer: I’m a part-time student in the Animal Studies M.A. program at NYU, and we’ve had a few scholars come through talking about same-sex sexual behavior in their species of study. I realized that I’ve always assumed that natural selection wouldn’t call for behaviors that didn’t cause genes to spread in subsequent generations—and yet an explosion of research in recent years has established that same-sex sexual behavior is widespread. A conundrum!

I began to look into theories of why same-sex sexual behavior would persist throughout the animal kingdom. I found compelling individual articles, and some terrific scholarly texts (like Bruce Bagemihl’s Biological Exuberance and Joan Roughgarden’s Evolution’s Rainbow), but not a public-facing book, and found myself getting that feeling of urgency that means I’m going to be writing a new book.

MB: Who is your intended audience?

ES: I’ve long written young adult books, though most of my readers over the years have seemed to be adults, not teens. As I was looking into the diversity of animal sexuality, I remembered my experience of realizing I was gay when I was 11. I looked up “homosexuality” in an encyclopedia and learned that it was a psychological aberration caused by human culture or bad parenting. That accorded with the negative messaging I was also getting from our media. I wrestled with that for a long time, and a lot of LGBTQ+ young people don’t survive this internalized assumption that there is something wrong or unnatural about them. So I wrote the book to be accessible to a teen audience, though I anticipate that most of its readers will be adults.

MB: What are some of the topics you weave into your book and what are some of your major messages?

ES: The first work I had to do was paring down an immense field into accessible chapters. A recent study in Nature put the number of species with confirmed substantial same-sex sexual behaviors at 1,500 and counting. I decided to hone in on 10 emblematic animals, who would represent a diversity of evolutionary strategies and would each help answer a broader question about this field.

Doodlebugs, whose male-male couplings shook the 19th-century entomology world, help explore the history of human attitudes towards homosexuality.

Bonobos, an ape species that is in a rough tie with chimps as our closest relative and for whom female-female sex is the most frequent, help us look at how we might be underestimating the level of bisexuality (rather than hetero- or homosexuality) in animals.

Dolphins were a way of looking at male-male sex as a social survival strategy, with parallels to humans in various cultures throughout history.

Fruit flies help us examine the degree to which sexuality is genetic.

Same-sex parenting and polyamory among birds help to tease apart the relationship between sexual acts and same-sex bonding.

Japanese macaques were in some ways the most controversial example, at least to those who continue to consider animals to be evolutionary cogs: primatologist Paul Vasey studied the monkeys for decades and tested out various theories for why they have such frequent female-female sex. He ultimately concluded that there wasn’t an adaptive reason for it; they just wanted to.

I’m not trying to argue for human behaviors based on these animal examples. Animals do plenty of things that most of us wouldn’t want to see humans doing, like consuming their sexual partners after mating. But I am arguing that it’s no longer scientifically tenable to claim that LGBTQ+ humans are unnatural or that they don’t have analogues in the animal world.

MB: How does your book differ from others that are concerned with some of the same general topics?

ES: There are some notable academic heavyweight books in this field, foremost among them Bruce Bagemihl’s meticulously researched Biological Exuberance (1999). Queer Ducks (and Other Animals) aims to be a layperson’s read, using humor and a more journalistic approach to make the field of animal sex accessible to a broad range of readers.

MB: Are you hopeful that as people learn more about these topics they will be more understanding about human and nonhuman sexuality?

ES: Absolutely. One of the main realizations to come out of my research was that, freed from the shaming human societies attach to same-sex sexual behaviors, animals practice them casually and for social benefit. Whether heterosexual or homosexual, sex produces oxytocin, known as the “bonding hormone.” That makes for social alliances.

Our unchecked “Noah’s ark” assumptions that animals have sex only to procreate, aided by an overly narrow view of natural selection, have kept us from seeing all the diverse benefits sex can have for animals, beyond just procreation. I think learning about the diversity of sexual expression in nonhuman animals can only make us more open to the diversity of sexual expression we encounter in humans.

That’s if people learn about it, of course. This current rise of LGBTQ+ censorship in schools and libraries, based on a contagion theory of sexuality, is both highly damaging to queer populations and goes against this surge in scholarship. There’s no keeping sexual diversity out because it’s our heritage as animals.