Empathy

'Kindling' Asks Us to Think Deeply About Empathy and Apathy

Linnea Ryshke gently asks critical questions about our circle of moral concerns.

Posted October 23, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

I recently read and was moved deeply by poet and artist Linnea Ryshke's thoughtful and inspirational book Kindling, and immediately asked if she could answer a few questions about her collection of poems and artwork, much of which is based on her own experiences, including time interacting with the animals on an organic meat farm. Here's what she had to say.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write Kindling?

Linnea Ryshke: Kindling is intended to contribute to the body of artwork, literature, poetry, and theory that is asking us to hold the most difficult questions of our time. For me, one of the most imperative concerns is the need to broaden our moral circle of consideration and concern to include the more-than-human beings with whom we live on this planet.

MB: Who is your intended audience?

LR: I hope my book will reach the hands of people who might not normally consider the lives of farmed animals, or who might actively dismiss this topic. This is an aspiring goal, especially because books like these tend to run in the same circles. But my somewhat unconscious intention was to create a book that was intimate and came from my own vulnerability, therefore hoping to evade any kind of “holier than thou” tone. However, Kindling is not an easy read—it asks the audience to be patient, still, and brave. In this way, not everyone will be able to sit with it. But my hope is, through my gentle and honest approach, people will find themselves invited into the work, to hold this heartbreak with me.

MB: What are some of the topics you weave into your book and what are some of your major messages?

LR: Kindling is a three-part reflection on my experience working for a short time at a small, family-owned meat farm in Europe. The first section is comprised of poetry and photography that narrate the story by focusing on small, intimate moments that are laced with sensory and emotional detail. The second part takes the form of an essay and statement about my visual artwork created in the year after this pivotal experience. The final part is a short conclusion, what I call a prayer.

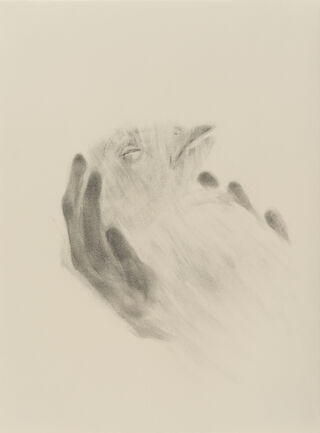

The psychological tensions between empathy and apathy, and care and harm, knit together many of the poems. Because I was taking part in the day-to-day operations, I began to embody the cognitive dissonance that manifests in this kind of environment. This was a small family farm of course, not near the kind of intensity of a factory farm, yet micro-aggression and violence was the norm and something I was a part of during that time. The quality of my touch was not, could not, be caring and kind. I acted in ways contrary to my ethical beliefs; in my life, I try to have as gentle a presence as possible, especially in the presence of nonhuman animals. For instance, there is a poem that describes when a quail escapes from her cage and “the claws of my hands lunged” to grab her. The small violence of this act singed my skin. I ask the reader to be with me in this uncomfortable reality: even in the “nicest” conditions of a small family farm, the logic of commodification persists, and with it, a lack of engagement in empathy, care, reciprocity, and respect for individual autonomy, which, to me, are the pillars of a human-animal ethic that we need to cultivate now more than ever.

I see art and poetry as critical not only in animal advocacy, but in the imperative work of shaking us awake at our most elemental level. In my eyes, our hyperactive, technology-reliant, commerce-driven social systems have made us disassociated from a feeling, empathetic, communal way of living. We need to practice the art of sensory attention and attunement to the life around us and within us. We need to build the capacity for sitting in silence or reverie. We need to cultivate patience for feeling the most uncomfortable of feelings. Without these skills, I don’t believe any meaningful change can be made. I understand art and poetry as essential in stimulating our empathetic and sensory capacities again and reorienting us to a slower, sensitive way of being.

MB: How does your book differ from others that are concerned with some of the same general topics?

LR: I feel there is a need and place for every kind of perspective and strategy when it comes to urgent issues like animal advocacy or the climate crisis. My own contribution is not what I would call “activist art.” It is not overtly didactic. Up until two years ago, my artwork was much more direct, but I found it was not affecting others the way I hoped. The tone of my work has changed to one that is more ambiguous and subtle, yet still melancholic and distressing. For me, I find art to be most compelling when it moves beyond rational comprehension and resonates within the most hidden part of us. It’s the aesthetics of the work, whether of a song, a poem, or painting, that can bypass all logical comprehension and communicate with the deep, nonverbal part of us. In this way, when the art is tasked to confront something as difficult as the violence towards nonhuman animals, Kindling seeks a balance between clarity and ambiguity. I want the audience not to “read the message” but “feel the resonance” of the poems and images.

MB: Do you feel optimistic that as people learn more about what you're doing they'll treat animals with more respect, dignity, and compassion?

LR: Honestly, as most people with their ear to the ground, who are aware of the myriad of ways in which the flourishing of nonhuman life is threatened by human activity, optimism can be hard to come by. The hard part of making art as a catalyst for change is that there are no clear metrics to measure outcome. Meaningful conversations are the only way I can understand the impact of my work. These conversations have the ability to shift one person's way of seeing and can then reverberate into the other lives touched by that person. I dedicate my small life to the immense undertaking of changing our relationship with nonhuman animals, knowing that my efforts won’t do a lot, but they will do some small thing. And that still matters.

References

In conversation with Linnea Ryshke.

Bekoff, Marc. Animals, Exploitation, and Art: The Work of Colleen Plumb. (A riveting interview about how artwork can foster compassion and empathy.)

_____. Art for Animals: Its Historical Significance for Advocacy. (An interview with Keri Cronin about her new book focusing on art and activism.)

_____. Art Behind Bars: Animals, Compassion, Freedom, and Hope.