Cognitive Dissonance

Grizzly Bear Expert Explains Who These Carnivores Really Are

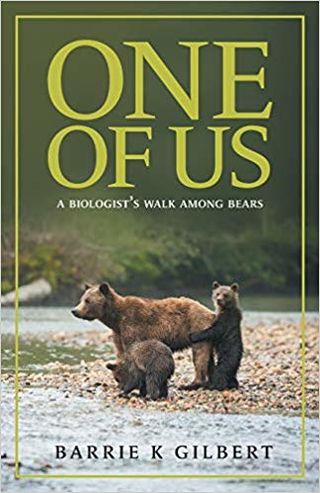

An interview with Dr. Barrie Gilbert about his myth-busting book, "One of Us."

Posted December 26, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

"Barrie Gilbert's fascination with grizzly bears almost got him killed in Yellowstone National Park. He recovered, returned to fieldwork, and devoted the next several decades to understanding and protecting these often-maligned giants...Drawn from his decades of experience, One of Us: A Biologist's Walk Among Bears explodes myths that depict grizzlies as bloodthirsty beasts that 'kill for pleasure' and reveals the intelligent, adaptable side of these astonishingly social animals."

"Gilbert’s new book is called One of Us: A Biologist’s Walk Among Bears. He believes scientists themselves have contributed to the grizzly problem by over-managing bears with excessive capturing and collaring, a practice that Gilbert believes 'is actually making bears man-haters, and in my book, I talk about it.'”

I've always been fascinated by grizzly bears and was thrilled to learn about a new book by bear-attack survivor, grizzly expert, and unwavering advocate, Dr. Barrie Gilbert. In One of Us: A Biologist's Walk Among Bears, the candor with which he discusses these amazing carnivores and his breadth of knowledge stilled me. (See interview with Dr. Gilbert: "Scarred by grizzly bear, biologist turns the other cheek.") GIlbert took some time to answer my additional questions about his wide-ranging, comprehensive, and outstanding book.

Why did you write One of Us?

I wanted to try to change the negative stereotyping of grizzly bears by having a mauling victim explain how interesting and adaptable grizzly bears can be if we act in a non-threatening way toward them. I also wanted to produce a book—for bear-viewing guides, naturalists, outdoor writers, and photographers—that can be used for education and awareness based on my 35 years of observational research on bear cultures made up of individually known grizzly/brown bears. It's important to alert people to the failure of the National Park Service (NPS) to follow the law (Organic Act) when self-interested stake-holders lobby Alaskan senators to influence the Secretary of the Interior in revoking 10 years of science-based plans for Brooks River bear conservation.

How does your book differ from other books on bear ecology and behavior?

I write as a field ethologist using strictly non-invasive anthropology-like methods. This method illuminates the lives of individual bears and bear-human interactions employing vast collections of quantitative data on bear learning, social behavior, and social transmission of learned traits. The book is personal, including mostly my research with students over a lifetime of work and from the perspective of an attack survivor intent on defending grizzlies and their habitat.

How did your accidental mauling influence your commitment to continuing the study of grizzly-human interactions and conflicts?

My recovery was followed by much TV coverage and attention to my injuries. As I became more frustrated with the casting of grizzly bears as vicious carnivores, I decided to use the accident as a hook. The cognitive dissonance, I hoped, would help change attitudes, as in “if this guy with his nasty experience can go back on the ground unarmed, then grizzlies and humans may be able to coexist.”

Who is your intended audience?

I aimed for a broad range of people interested in animals, especially wildlife conservationists, activists and guide-naturalists working for eco-lodges or leading nature tours. The book might also be of interest to hunters and hikers to reduce irrational fear of grizzly bears.

What are your major themes and messages?

"Despite the bad press that grizzlies get, Gilbert said violent grizzly encounters are far less common than fatal attacks by pet dogs."

Grizzly bear populations in different locations (Pacific Coast, Rocky Mountains) have different learned cultures and interaction responses to people. For us, the message about well-fed bears being calm among people points to fewer conflicts where good habitat/food is maintained. Grizzly bears need not scare people if they learn how to be alert and respond appropriately. The broader public enjoys viewing bears and no longer supports hunting of grizzlies as our values evolve.

What are some of your current projects?

As part of my activities for grizzly bear conservation in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), I provided testimony in-person to a Natural Resources committee of Congress, making a case that delisting of grizzly bears is premature, inimical to healthy expansion and connectivity of bears. Moreover, the states around the GYE have plans to hunt bears at unsustainable numbers.

I also allied with the Sierra Club and a former Katmai National Park superintendent to find legal help to challenge the unexamined reversal of policy for Brooks Camp’s future. I was invited by British Columbia’s Wildlife Branch to review their new and revolutionary bear viewing strategy. It was written by biologists and guides, as well as academics, who were independent of the prevailing male-dominated mind-frame of hunters. This initiative paralleled the expansion of bear-viewing operations and the establishment of the Commercial Bear Viewing Association of British Columbia (CBVA). The CBVA has a director who keeps tabs on and networks with the BC political establishment. My contacts with her leave me optimistic about the future direction of grizzly bear management in BC, which could be a model for a reevaluation of Alaska’s current mismanagement of grizzly bears.

Is there anything else you'd like to tell readers?

We could well be losing our cultural connection to our support system: Nature. I have been guilty of drinking the Cool Aid that Canada is still defending wild places. To me, the issue of The Public Trust—the principle of stewardship—is our primary cultural value toward the natural world. This has its roots in preserving whole functioning ecosystems and not a series of token postage stamp refuges with minimal populations of merely representative iconic species, mostly threatened and endangered species. Among my favorite chapters is one called "Science Friction."

The tragedy, ecologically speaking, of paying lip service to natural values while ecosystem-destructive “development” actions of mining, forestry, dam building, and other habitat destruction gain support as jobs and economic development. We are faced with future loss of the earth’s productive capacity. One only has to witness the short term pay-off of hydropower of huge dams, soon to fill with silt, against the everlasting return of unfarmed salmon that could provide food for us for thousands of years.

______

Many thanks, Barrie, for such an informative and up-close-and-personal interview. Your myth-busting, detailed, wide-ranging, and candid book serves as a wonderful model for what is needed for all nonhumans, especially perhaps for those who are misunderstood, feared, and killed rather than appreciated for who they truly are. I couldn't agree more when you say, "bears and humans would get along a lot better if people would try harder to understand bear behavior."