Relationships

Dogs, Captivity, and Freedom: Unleash Them Whenever You Can

Most dogs live very constrained lives, and there's much we can do to free them.

Posted March 15, 2019

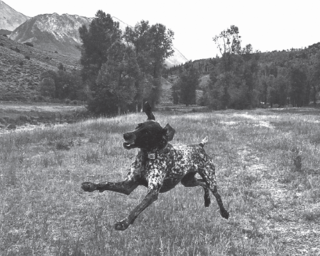

“You may not agree, you may not care, but...you should know that of all the sights I love in this world—and there are plenty—very near the top of the list is this one: dogs without leashes.” (renowned poet, Mary Oliver)

Companion dogs live highly constrained lives, and there's a lot we can easily do to give them considerably more freedom and allow them to express their dogness. In Unleashing Your Dog: A Field Guide to Giving Your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible, Jessica Pierce and I offer numerous suggestions for living with dogs in ways that enhance everyone’s quality of life and expand the freedom for dogs to really be dogs. For example, allowing dogs to exercise their senses is critical for giving dogs the most freedom possible. All in all, dogs want and need much more than they usually get from us.

Focusing on dogs as captive beings, let's begin with leashes because they are symbolic of our complicated relationship with our canine companions: Leashes literally tie us together, one on each end. To people, the leash represents going out into the world with our dogs and giving them time to sniff, run, play, chase, have fun, roll, pee, poop, hump, and otherwise express themselves. To dogs, the leash likely represents these things, but it is also a tether that constrains their freedom because the leash is our means of control. It ensures that dogs are only allowed to go where we say, when we say, under our terms. Unleashing dogs means finding ways to let them have more freedom.

Despite human imposed constrains, most people who choose to share their home and heart with a dog do their best to provide a good life for their canine companion. We asked a number of people what they most value for their dog, and the two answers most commonly given were: “I want my dog to get to be a dog,” and “I want my dog to be happy.” These two values are closely linked. Most people want dogs to express dog behaviors, to be satisfied on their own terms, and to “be themselves.” This is important because a great deal of what we ask our pet dogs to do is undog-like and puts aside their doggy natures. For example, we ask them to sit inside alone for hours on end, and we ask them to walk slowly at the end of a rope instead of allowing them to dart here and there, deciding for themselves what deserves sniffing and exploring. We ask them not to bark, not to chase, not to hump, and not to sniff other dogs’ butts. People who love dogs want their dog to be happy, and, to be happy, dogs need the freedom to act like dogs. Greater freedom means greater happiness.

Consider, for example, the experience of Marilyn and her rescue dog, Damien. Within a day of bringing Damien home, Marilyn realized that she said, she’d “taken on a handful plus.” She had completely underestimated how much she would have to change her life to accommodate her canine companion. She hadn’t anticipated the depth and breadth of the commitment it required to give Damien what he wanted and needed, and she was “totally dumbfounded about what to do.” How could she give this handsome guy the best life possible, given the constraints of her own life? After learning about dog behavior, Marilyn soon realized she’d have to adjust and give up some of her own “stuff” to give Damien what he needed. Damien was fully dependent on her for everything. But Marilyn also came to see that accommodating Damien in order to give him as much freedom as possible also enriched her own life. Though the changes she made felt like a sacrifice at first, she came to realize they weren’t sacrifices at all because of what Damien gave her in return. Months later, Marilyn said that she and Damien were the happiest couple in the world. She admitted that she got pushed to the limit on occasion, and Damien’s tolerance of her “humanness” was critical. He seemed to understand that she was doing the best she could and wanted him to be a happy dog.

Jim’s experience with his young rescued mutt, Jasmine, was similar, except that Jasmine had been severely abused as a youngster. As Jim put it, “She was the neediest individual I’d ever met— canine, feline, or human.” However, once Jim came to realize that he was Jasmine’s lifeline, things changed. Jim worked hard to help Jasmine adapt to her life with Jim, and what began as an iffy relationship slowly evolved into one of mutual respect and trust. Jasmine helped Jim understand that dogs often struggle to adapt to human environments, particularly when dogs have had negative experiences with human caretakers.

Dog companions are captive animals, in that they are almost completely dependent on humans to provide for their physical, emotional, and social needs. This does not mean that dogs can’t be happy in human homes, but rather, humans often have a good deal of work to do to ensure that their canine and other housemates live with as much freedom as possible. Fortunately, unleashing your dog, literally and metaphorically, is fun for all involved.

What does "being captive" mean?

According to the online Etymology Dictionary, the noun captive means “one who is taken and kept in confinement; one who is completely in the power of another.” The word’s roots come from the Latin captivus, “caught, taken prisoner,” and from capere, “to take, hold, seize.”

Dogs are typically portrayed as happy-go-lucky members of our extended human families, without a care in the world. Indeed, the phrase “It’s a dog’s life” is sometimes used to describe days filled with laziness and pleasure. Aside from trained working dogs, all our dog companions do, after all, is sleep, laze around, eat, play, and hang out with friends. What could be easier, especially when someone reliably plops down a bowl of food several times a day? We are here to tell you that the lives of homed dogs aren’t necessarily all fun and games and that living as the companions of humans comes with some important compromises on the part of dogs. To adapt to human environments and expectations, dogs must sacrifice some of their “dogness.” Despite our best efforts to provide a good life, and without quite realizing it, we usually ask them to live like us rather than like dogs. However, in order to successfully allow and even encourage our dogs to be dogs, we need to understand who dogs really are and how to help them express their dogness within our world.

When conservation biologist Susan Townsend, my last doctoral student at the University of Colorado in Boulder, heard about Unleashing Your Dog, she told me that whenever she comes home to Angel, a Chihuahua mix, she asks, “How’s my little prisoner doing?” Susan’s greeting, although said in companionable jest, reflects an important reality.

Simply put, “being captive” means that your life is not your own, that the contours of your daily existence are shaped by someone else. It doesn’t necessarily mean that you are mistreated or unhappy or that your captors intend to harm or punish you. Being captive refers to a type of existence, not its quality. It means being confined to a certain space, one not necessarily of your choosing. It means you lack the ability to choose what you do, who you see, who and what you smell, and what and when you eat. It means, at times, being forced to do certain tasks others ask of you. It means depending on someone else to provide the basic necessities of life, like food and shelter, along with opportunities for meaningful engagement with others and the world. In these ways, dogs kept as pets are captive animals, and humans are their captors because we control all these aspects of their lives. This is the crucial starting point for understanding our relationships with, and our responsibilities toward, our furry friends. No matter how loving human caretakers are, companion dogs must cope with an asymmetrical relationship. To live in our world, we require them to give up some of their freedoms and natural canine behaviors.

Living with dogs involves a careful balance. Some constraints are essential for the safety of dogs and humans, and yet if we aren’t careful and extremely attentive to what our dog needs, these constraints can severely compromise our dog’s quality of life and ability to thrive. One goal Unleashing Your Dog is to examine and become aware of the constraints we place on dogs, to identify those that are unnecessarily strict and those that are so subtle that we might not even realize we’re depriving our dogs of freedoms they need or want. You might say, with dogs, we have made a kind of Faustian bargain: To bring dogs into our lives and love them, we have had to compromise their freedoms and, in some ways, compromise their well-being.

The antidote for captivity is freedom: The Ten Freedoms for dogs

The antidote for captivity is freedom. Clearly, there is a basic tension between captivity and freedom, and dogs exist within this zone of uncertainty. Although dogs are captive (there’s no getting around this), they can nevertheless enjoy remarkable degrees of freedom within human environments.

Like captivity, freedom isn’t black and white, but rather comes in shades of gray. Dogs in our society live under a whole range of conditions, and they experience varying levels of captivity-related stress and varying levels of freedom. Further, the way homed dogs live varies widely across the globe and even house to house. It’s hard to speak in generalities since there are always variations and exceptions. More to the point: Each dog and each person is different. Each dog experiences certain deprivations more keenly, and each person will find certain enhancements and freedoms easier to provide than others. Every dog deserves the best life we can offer, and this “best life” means giving them the greatest amount of freedom and the fewest experiences of captivity-induced deprivation we can provide.

The Five Freedoms are a popular cornerstone of animal welfare. First developed in 1965 and formalized in 1979 by the UK’s Farm Animal Welfare Council, the Five Freedoms were designed to address some of the worst welfare problems experienced by animals used within industrial farming (or “factory farming”). Since their development, the Five Freedoms have been applied to an increasingly broad range of captive animals, such as those living in zoos and research labs.

Over the past few years, the Five Freedoms have also made their way into discussions of companion animal welfare. They provide a good starting point for thinking about enhancing freedoms for dogs. In Unleashing Your Dog we adapted and expanded the original Five Freedoms into Ten Freedoms that should guide our interactions with dogs. Freedoms one to five focus on freedoms from uncomfortable or aversive experiences. Freedoms six to ten focus on freedoms to be dogs.

Like all animals, dogs need the following:

1. Freedom from hunger and thirst

2. Freedom from pain

3. Freedom from discomfort

4. Freedom from fear and distress

5. Freedom from avoidable or treatable illness and disability

6. Freedom to be themselves

7. Freedom to express normal behavior

8. Freedom to exercise choice and control

9. Freedom to frolic and have fun

10. Freedom to have privacy and “safe zones”

Even the most well-cared-for dogs—those who are doted upon, have soft beds and tasty nutritional food, and get good veterinary care—may experience deprivations of which their owner is largely unaware. This is because a great many people who choose to share their home with a dog don’t know very much about dog behavior. One report on pet owners’ knowledge of dog behavior, for example, found that 13 percent of people had done no research into dog behavior prior to acquiring a dog, and only 33 percent felt “very informed” about the basic welfare needs of dogs. Although some dog owners have read shelves full of books about the natural history, ethology, and care of dogs, many others just fly by the seat of their pants. Dogs are amazingly adaptive and resilient and find ways to survive even in environments that aren’t particularly dog-friendly. But obviously, most people want their dogs to thrive, not just scrape by, and the best way to help them do that is to learn as much as possible about who dogs really are and what they need from us.

There’s an upside to giving our dogs more freedoms: We reap benefits, too. Happy and contented dogs tend to be easier to live with, resulting in happier and more contented guardians. “Problem” canine behaviors related to anxiety or frustration can resolve themselves, giving us more time to enjoy our friendship with our canine companions. People sometimes fall into bad habits of complaining about how difficult dogs are to care for and live with. At dog parks, we’ve heard numerous people say something like, “Gosh, I’ve had to change my whole day around taking her to a dog park.” But you know who else experiences more freedom and satisfaction when we unleash our dogs more often? We do. Letting go of the leash is a benefit that helps everyone.

It's also important to remember that there is no "universal dog." Each and every dog is an individual with a unique personality. And, our relationships with dogs are grounded in and guided by personal values. Sometimes these are openly acknowledged, and sometimes they are unstated but reflected in our actions. People differ in how they choose to live with their nonhuman companions, but it is useful to make these values explicit if you have invited another animal into your life or plan to do so. The first question is the one we pose above: What do you consider to be a good life for your dog, and how can you help your dog achieve this kind of life? Make a list of your goals; write them down.

Where to from here? Unleash your dog as much as you can

Our relationships with dogs must incorporate give-and-take and be steeped in on-going negotiations between dogs and humans, mutual respect and tolerance, and lots of love. It's a huge responsibility to take a dog into your life.

“Unleashing your dog” is both literal—dogs need more time off leash—and metaphorical. We need to continually work toward increasing the freedoms that our dogs experience, thereby unleashing their potential to live life to the fullest. And with that, let’s unclip the leash and begin enhancing the lives of the dogs we love so much. Here are 10 ways to make your dog happier and more content:

1. Let your dog be a dog.

2. Teach your dog how to thrive in human environments.

3. Have shared experiences with your dog.

4. Be grateful for how much your dog can teach you.

5. Make life an adventure for your dog.

6. Give your dog as many choices as possible.

7. Make your dog’s life interesting by providing variety in feeding, walking, and making friends.

8. Give your dog endless opportunities to play.

9. Give your dog affection and attention every day.

10. Be loyal to your dog.

Humane educator Zoe Weil often exclaims, "The world becomes what we teach." We also can say "Dogs become who we teach them to be." We need to teach them well, and when we do, it's a win-win for all. Our relationships with dogs must incorporate give-and-take and be steeped in on-going negotiations between dogs and humans, mutual respect and tolerance, and lots of love. It's a huge responsibility to take a dog into your life. Unleashing them is an excellent way to give them considerably more freedom and to allow them to express who they truly are, their dogness.

For other essays about unleashing your dog whenever possible see "Dogs Should Be 'Unleashed' to Sniff to Their Noses' Content," "Oh Goodness, Why'd My Dog Erin Just Eat Something So Foul?", "Being Touched Is Fine For Some Dogs, But Not for Others," "How Dogs See the World: Some Facts About the Canine Cosmos," "Stripping Animals of Emotions is 'Anti-Scientific & Dumb'," and "10 Ways to Make Your Dog Happier and More Content."

Some of the above is excerpted from Unleashing Your Dog: A Field Guide to Giving Your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible. I thank Jessica Pierce for her collaboration on this and other projects.