Fear

Pit Bulls: The Psychology of Breedism, Fear, and Prejudice

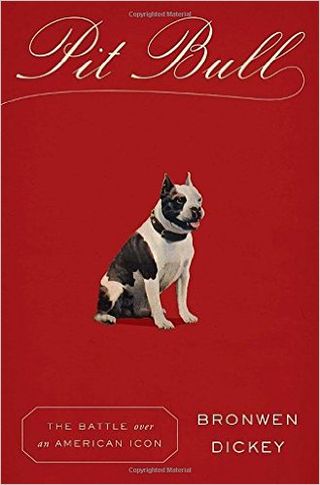

Bronwen Dickey's new book "Pit Bull" analyzes how a breed became demonized

Posted June 2, 2016

The psychology of breed stereotypes, fear, and prejudice

Stereotypes abound about how individuals of different breeds of dog always or almost always behave. This sort of breedism very frequently reaches its apogee with pit bulls. My own encounters with pit bulls have uniformly been friendly. Once, on a trip to Cincinnati, I met a pit bull at a gas station who was first bought to be a fighter but who turned out, according the man who had bought him, to be "a wimp." When I asked the man about his dog he told me that he had purchased him to "make some money" in dog fights, but when his dog refused to fight -- and they both were ridiculed -- he came to see his dog and others as individuals and vowed never ever to engage in dog fighting.

As a student of animal behavior in many different species I've always been keenly interested in individual differences among members of the same species. Researchers call these "intraspecific differences." And, because I've met a good number of pit bulls with whom I've connected in very positive ways, I've wondered about how these dogs became demonized as supposedly the most dangerous of dogs. I figured that the story that continues to plague these dogs was a long one and I was thrilled to receive Bronwen Dickey's new book called Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon (the Kindle edition can be found here). The book's description reads as follows:

The hugely illuminating story of how a popular breed of dog became the most demonized and supposedly the most dangerous of dogs—and what role humans have played in the transformation.

When Bronwen Dickey brought her new dog home, she saw no traces of the infamous viciousness in her affectionate, timid pit bull. Which made her wonder: How had the breed—beloved by Teddy Roosevelt, Helen Keller, and Hollywood’s “Little Rascals”—come to be known as a brutal fighter?

Her search for answers takes her from nineteenth-century New York City dogfighting pits—the cruelty of which drew the attention of the recently formed ASPCA—to early twentieth‑century movie sets, where pit bulls cavorted with Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton; from the battlefields of Gettysburg and the Marne, where pit bulls earned presidential recognition, to desolate urban neighborhoods where the dogs were loved, prized—and sometimes brutalized.

Whether through love or fear, hatred or devotion, humans are bound to the history of the pit bull. With unfailing thoughtfulness, compassion, and a firm grasp of scientific fact, Dickey offers us a clear-eyed portrait of this extraordinary breed, and an insightful view of Americans’ relationship with their dogs.

An interview with Bronwen Dickey

It's always good to hear from authors themselves, and I was fortunate enough to be able to conduct an interview with Ms. Dickey. In places it's necessarily rather detailed because some of the issues really need to be fully cashed out. I hope you will read the entire interview as Ms. Dickey put a lot of work into it.

Why did you write Pit Bull?

I wrote Pit Bull because I felt that the shadow history of the American dog had never been fully explored. Across America there were millions of families living normal, uneventful lives with animals the media portrayed as monsters, and I wanted to understand how and why this stereotype came into being. What I learned was that the frightening image of the pit bull has a lot more to do with our own fears and prejudices than it does with animal behavior.

Why do you think so many people don't like these awesome dogs without ever knowing one?

I think H.P. Lovecraft was right about this one: "The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown." If you've read horrifying stories about pit bulls and you don't have any positive first-hand experiences to put those stories in perspective, the reptilian part of your brain that modulates fear can guide your decisions much more easily. As I say in the book, you can't reason someone out of something he wasn't reasoned into.

How do you reconcile that pit bulls are responsible for such high frequencies of dog bites?

No one can agree on how the term "pit bull" should be defined, which immediately creates an enormous problem with bite statistics. Contrary to what most consumers of media reports think, "pit bull" does not refer only to one breed—the American pit bull terrier—but at least four: the APBT, the American Staffordshire terrier, the Staffordshire bull terrier, and the American bully. Right off the bat, the bite stats that list "pit bulls" as one "breed" are failing to acknowledge this, which invalidates the comparison. How can you compare specialized breeds (like the Labrador retriever, German shorthaired pointer, etc.) to a giant group of four breeds that have been lumped together? It would be like comparing the crash rates of the Ford Explorer, the Toyota Tacoma, and all "sedans." That isn't sound statistical methodology.

As if that weren't bad enough, an increasing number of generic, mixed-breed dogs have been thrown into the "pit bull" category because they have large heads, smooth coats, or brindle coloring. In the words of one shelter veterinarian, "We used to call mixed-breed dogs 'mutts.' Now we call them all 'pit bulls.'" The latest research into the accuracy of visual breed identification shows that these haphazard guesses are incorrect over 87% of the time.

The breed identification of the dogs listed in medical bite reports is never verified by independent sources. Medical professionals leave it to the patient or patient's guardian to fill out the paperwork on what kind of dog is responsible, and often people have no idea what kind of dog it was. If I am bitten by an American Eskimo dog but I'm not familiar with that breed and I put down "Siberian husky" on the form (because that's what it looks like to my untrained eye), it is listed as a Siberian husky bite. This is one of the MANY reasons that the American Veterinary Medical Association stresses that "dog bite statistics are not really statistics."

In order to know if something is "disproportionate," you have to know its correct proportion, and when it comes to the breed distribution of American dogs, we simply don't have the info to know how many dogs of each breed there are. Kennel club statistics are shrinking, and dogs sold as purebreds aren't required to be registered with clubs, anyway. Hobby breeding and backyard breeding are rampant. Even basic licensing compliance is shockingly low (sometimes, single-digit percentages) in many major metropolitan areas.

Those caveats aside, what we *do* know is that the number of Americans who consider themselves "pit bull owners" is steadily growing. According to several surveys of veterinary medical records, "pit bulls" (however loosely defined) are among the top-five most popular pets in 38 states. Because dogs bearing this label have been stigmatized and pushed to the margins of society for so long, their owners often don't have access to the same pet-care resources and information about animal husbandry that others take for granted. Animals in deprived areas can easily be affected by the same cycles of desperation, poverty, and violence that plague their human caretakers.

Dog bites are highly contextual, yet stark listings of "bites by breed" do not take this into account. This is why the CDC stopped tracking fatalities by breed: Epidemiologists there realized that there were so many contributing factors involved in each incident, and narrowing down such complex events to one factor was misleading and potentially dangerous

Can you say something about Dogsbite.org?

While polished and professional looking, Dogsbite.org relies almost exclusively on media reports for its content, and media reports are often highly inaccurate. The site's founder is also contemptuous of people in the relevant sciences, including those at the AVMA, the CDC, the Animal Behavior Society, etc. She refers to them as "science whores," which alone is enough to discredit her claims. (I discuss this at length in chapter 11 called "Looking Where the Light Is".)

What's your major take-home message(s)?

Most of all, I hope that readers will come away from the book with a heightened sense of skepticism—even skepticism of me! I don't want anyone to believe anything that is presented to them just because I said it. I encourage them to check out the citations and read the peer-reviewed literature for themselves. I found way too many papers that had slipped through the review process because no one checked their citations. Scientific literacy is so important to democracy, and right now, at least in this country, it's at an all-time low. Many people don't know where the statistics they see in the news come from, and as good citizens, we need to be able to determine which sources are credible. Just because it's on the Internet doesn't mean it's legitimate.

What's your next project?

I don't want to say too much about it, lest I jinx myself, but it will be related to the War on Drugs.

Is there anything else you'd like to mention?

Nope. I think that about covers it. Thank you so much for reading the book, and for this Q&A!

Beware of breed-wide stereotypes and focus on individuals

I learned a lot from Pit Bull and also from my interview. In a number of recent essays about dogs (and also one on sharks called "Shark Personalities: A Shark Isn't a SharkIsn't a Shark"), I've stressed how important it is to focus on individual animals because too many general statements are made that border on being myths about these fascinating animals (please see "Why Dogs Belong Off-Leash: It's Win-Win for All" and links therein). Pit Bull is worthy of a wide global audience and I hope it receives the attention it deserves.

Note: Anonymous and ad hominem comments will not be accepted.

Marc Bekoff's latest books are Jasper's Story: Saving Moon Bears (with Jill Robinson), Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation, Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed: The Fascinating Science of Animal Intelligence, Emotions, Friendship, and Conservation, Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence, and The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson). (Homepage: marcbekoff.com; @MarcBekoff)