Relationships

Actionable Advice for the Lovelorn from Ancient Rome

Stoic advice from 2,000 years ago anticipates CBT—and can still help us today.

Updated July 24, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- The Roman poet Ovid has 38 practical recommendations for getting over unrequited love or a painful breakup.

- Many of Ovid's recommendations are rooted in Stoicism, and hence are identical to strategies found in CBT.

- This post reviews Ovid's first six recommendations.

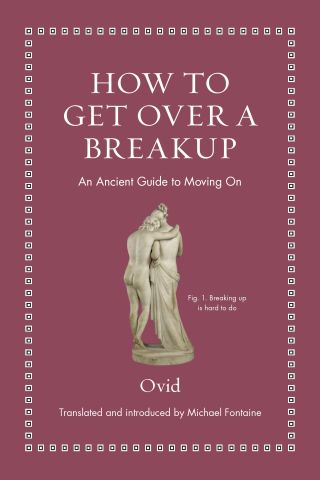

This post adapts material from my new book, How to Get Over a Breakup: An Ancient Guide to Moving On, and is the first in a series. For part 2 see here.

Breaking up or getting divorced is horrible. It feels world-ending. All kinds of relationships come to an end or change, and futures we had dreamed of will never happen.

Getting rejected in love is almost as bad. You finally muster the courage to ask some gorgeous or incredible person out, or make it known you'd like to be asked out, and you're met with…no. Why? Because your advances are unwanted. You're unattractive. It’s that simple. She or he just...isn’t into you.

Ouch.

Oh, and it gets worse. Unrequited love can play games with our minds, turning many of us into social media stalkers. And with breakups, practical problems ensue. Sometimes we need all new friends, or a new place to live. That doesn’t happen with getting blown off, but it sure does make things embarrassing the next time we see our crush in person or on social media. Or find out we’ve been unfriended or even blocked.

There are no easy fixes to these problems, but there are proven remedies to help us through such times. As long ago as the time of Jesus—fully two thousand years ago—a man in ancient Rome wrote an entire book on this very theme.

Now, psychotherapy is surely not the first image that ancient Rome conjures up. The Colosseum, maybe, or a gladiator.

But a clinical psychologist? A relationship counselor?

And yet, it’s true. Two thousand years ago, the Roman poet Ovid wrote a self-help manual for lovelorn readers. Titled Remedies for Love, his book is the only “how to get over a relationship” guide in all of the ancient world.

Now, if you’ve ever heard of Ovid (43 BCE–17 CE), it’s probably in connection with a more famous poem he wrote titled Metamorphoses. Metamorphoses, which means Changes of Shape, is Ovid’s masterpiece. It is a massive retelling of mythological stories in classical epic form. Most stories end with a character transforming into a new shape or state or being, with sexual attraction or repulsion typically serving as the catalyst of such changes. In narrating each story, Ovid explores the psychology of love in many sensitive and surprising ways.

Before writing that poem, however, Ovid had published the self-help poem I’d like to discuss here. He wrote it for readers based in the city of Rome itself, and he did that because, in Ovid’s view, Rome was the city of romance. Romeos were everywhere, and so were Rome-grown beauties. He wanted to help them—both women and men alike—and to do that, in the year 1 CE, he published a poem titled Remedia Amoris, or Remedies for Love. The poem is both hilarious and practical. It has much wisdom and a great deal of wit.

In it, Ovid offers us fully 38 strategies for coping with and getting over unrequited love. I’ve listed all 38 recommendations here. In this short series of blog posts, I’d like to review his recommendations and offer context, quotations, and modern parallel situations to illustrate what exactly Ovid means.

Before getting to them, it’s worth noting an astonishing convergence of psychotherapeutic practices between Ovid’s time and our own.

Ovid did not believe in pills or drugs to help with a breakup. Where, then, did he get his ideas on coping with or “curing” love?

The answer is that he found them in Hellenistic philosophy. Just as there are several major “schools” or brands of psychotherapy in competition today, so there were several major “schools” or denominations of philosophy in competition in ancient Rome. The Stoics, the Epicureans, the Peripatetics—all offered their adherents books and therapeutic strategies for dealing with woe.

In contemporary America, the ancient philosophy of Stoicism is enjoying a massive revival. Books, websites, and podcasts abound. Many people find the insights and mantras helpful in their own lives. Readers of this website probably already know that CBT bears a marked similarity to ancient Stoicism. As psychologist Donald Robertson has pointed out, that’s not a coincidence, because CBT is Stoicism.

I’ll explore that connection in another post. Meanwhile, here are Ovid’s first six strategies for coping with unrequited love. How many of these might work for you?

- Never have “nothing to do.” Ovid means you should keep yourself occupied at all times. An absolutely classic recommendation. Don't sit around the house. Get up. Do something, he says, and you'll be safe.

- Go out and fight on campaign—wearing a toga, downtown. In plain English, Ovid means you should become a lawyer. If that sounds strange, then remember that becoming a lawyer was the primary occupation for young men on the make in ancient Rome. Legal training and public speaking were the foundation of all education back then. In modern terms, then, a therapist might suggest a lovelorn person throw him- or herself into their career or schoolwork.

- Heed the call of duty. If you don’t become a lawyer, you can join the army. In Ovid’s time, soldiers were deployed all throughout Rome’s massive, sprawling empire, where new people and new adventures awaited. And getting shot at, as the saying goes, tends to focus the mind on important matters.

- Farm life can easily fix any fixation you have. If you don’t become a lawyer or a soldier, you can get out of the city and back to nature. The beauty of this recommendation is that’s essentially equivalent to our suggestion that you “touch grass.” That is, ditch the screens and apps and games and get out in the real world.

- Venus has often turned tail and shamefully fled after Diana prevails! Along the same lines, you can cultivate an outdoor hobby. Because no one worked out for fun in his time—exercise was entirely connected with military drills—Ovid suggests hunting or fishing or bird-catching. Today, though, you might consider joining a soccer or a softball team. Meet new people, burn some calories, distract your mind.

- Get out and go far away. Take a long trip out of town. This is exactly like our saying, “out of sight, out of mind.” Ovid believed it, too, and it brings me to my conclusion for this post. Which is this:

With the onset of social media in the 21st century, Ovid’s ancient advice has suddenly become relevant in a new way. Two thousand years ago, Ovid was writing for an audience based in the city of Rome. His readers couldn’t just up and leave town if a relationship went bad. They had to find a way to move on, while realizing they’d probably run into their ex again.

It’s the same in our hyperconnected world today. Twenty years ago—before Facebook, X, Instagram, and the rest—you could still up and leave town.

Not anymore. You may unfriend your ex, but the algorithm ensures you’ll see reminders—and friends of “friends”—for a long time to come.

For anyone who finds our new reality painful, Ovid may have something to tell us yet.

References

Fontaine, Michael (translator). 2024. Ovid: How to Get Over a Breakup.: An Ancient Guide for Moving On. Princeton University Press.