Wisdom

How Hypocrisy Becomes the Mind-Numbing Norm

To win fights, we lay down moral laws we can’t, won’t, and shouldn’t live by.

Posted December 13, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- To win arguments, people often draw hard lines that make their opponents sound bad and themselves sound good.

- People can get addicted to holy warring, whereby the more everyone wars, the holier they feel — and the holier they feel, the more they war.

- Failing to live by their own standards, people become hypocrites, ignoring the practical moral challenge expressed by the serenity prayer.

In arguments and fights, or really, anytime we’re angry or frustrated with someone, we tend to start pointing fingers, accusing our opponents of having crossed whatever moral line makes us feel right and righteous. They’re on the bad side of the line; we’re on the good side.

And where’s the line? Wherever we need it to be in the moment. We become holy warriors for any crusade against line-crossing that serves us.

Holy war cru-sadism

Since nothing’s dirtier than war nor cleaner than holiness, “holy war” is an oxymoron. We feel cleaner by accusing our opponents of being dirty. Indeed, we feel so clean in comparison to their dirtiness that we feel it’s our duty to fight dirty to win against these evildoers.

Holy warring readily becomes a vicious-cycle addiction. It feels good to accuse others of crossing moral lines. It makes us feel holy, and if we’re holy, it’s our duty to police unholy line-crossers, which in turn makes us feel still holier and more duty-bound to police them. The more we war, the holier we feel. The holier we feel, the more we war.

Outward outrage makes us forget our own failings, which can be quite the self-pleasuring buzz. For example, if you accuse someone of being a “quitter” you’re likely to forget that you’ve ever quit anything, which, of course, like everyone, you have.

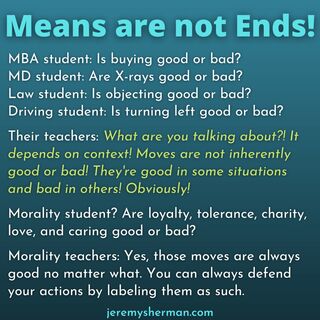

Loaded moral terms = bogus moral laws

“Quitter” sounds bad which implies a bogus moral rule: Leaving=immoral. One should never leave anything. One should always be loyal (good), committed (good), and dedicated (good). One should never abandon (bad) cut and run (bad) or be a quitter (bad).

Now, if you’re on the receiving end—accused of being a quitter, you can wage the opposite bogus holy war. You’re not quitting. You’re emancipating (good), liberating (good), and freeing (good) yourself from oppression (bad) by a bully, gaslighter, tyrant, psychopath, narcissist (bad, bad, bad, bad, bad).

Serenity-prayer moral realism

Obviously, there’s no rule that one must never leave or stay. We all stay and leave things with good and bad consequences. You know what it’s like to regret having stayed with something too long or too short. Likewise, you know what it’s like to have tried to improve the un-improvable and to have given up on improving something you could have improved. Wisdom is trying to minimize both kinds of errors.

That’s the point of the serenity prayer. You don’t want the serenity to accept what you could improve or the courage to try to improve what can’t be improved. You seek the wisdom to notice the differences that make a difference to whether you should persevere or give up. There is no simple, successful formula like always persevere or always give up.

Minding the winding moral road’s opposite sides

Moral wisdom is just this kind of serenity-prayer noticing and it can be applied to all sorts of moral dilemmas. You don’t want to trust the untrustworthy or distrust the trustworthy. You don’t want to be intolerant of what should be tolerated or to tolerate what shouldn’t be tolerated. You don’t want to be open-minded to terrible ideas or closed to good ones. You don’t want to speak when you should be quiet or quiet when you should speak. The list goes on.

But we lose sight of that when we’re employing bogus moral principles in the moment to prevail, drawing artificial lines with us on the good side and our opponents on the bad side.

I think of moral wisdom as navigating opposites, wise-driving on life’s changing, forking, and winding roads. You have to watch out for danger on opposite sides of the road. When you’re influenced by bogus moral rules like “never be a quitter; always be loyal,” you’re watching one side of the road at risk of crashing on the other. It’s wiser to mind the winding road, recognizing that there are two sides of it.

Indeed my idea of equanimity is being equally anxious about being too much to one side and the other. For example, the best equanimity I can hope for is being mildly concerned that I’m either too assertive or not assertive enough, too loyal or not loyal enough, too open-minded or not open-minded enough, quitting too soon or quitting too late.

Two opposite hypocrisies, often combined

Bogus rules like “quitting is always bad” or “liberation is always good” suggest otherwise. They remain very popular because they come in handy when we’re desperate to prevail in debates. Such rules are at the heartless heart of moralizing—which can be done in any variety of tones from whispered pedantic “counseling” to fierce moralizing blackmail, as though if you quit, your moral reputation will be ruined.

Since the rules are bogus, no one really follows them, though they might virtue-signal that they do. As a result, we end up with two kinds of hypocrisy:

Fundamentalist hypocrisy: “I know the hard lines no one should ever cross. I never cross them and when I do, well, I make lots of exceptions for myself which is my right since I'm the authority on where to draw the hard lines.”

Cynical hypocrisy: “Since fundamentalist hypocrites, those lines are bogus. There are no lines, which means I don't have to worry about being consistent."

Often, you’ll get both from the same hypocrite: “How dare you cross that moral line and so what if I do since you do too?”

The alternative to these popular hypocrisies?

Ironic Guesswork: There are moral lines not to cross but we can only guess where they are. We’re all bozos on this rickety bus riding these winding potholed roads. We have to mind the roads, looking for the lines, but we will all guess wrong and need to laugh and learn when we do.

References

Sherman, Jeremy (2021) What's Up With A**holes?: How to spot and stop them without becoming one. Berkeley, CA: Evolving Press.