Attention

How To Minimize Drama

Some clues for sidestepping relationship rough spots

Posted September 16, 2016

Do you ever question people’s character? Do they ever question yours?

All of us can and do, even if just through subtle unconscious gestures. A raised eyebrow or weary sigh are enough to shift attention from whatever topic is on the table to how strangely the others around the table are handling it, insinuating in the process that there’s something wrong with them.

Questioning people’s character tends to escalate into “drama,” which can unravel friendships, leaving ex-friends thinking less of each other. Listen to anyone talk about ex-friends, and that’s what you’re likely to get, at least between the lines: Something was wrong with them.

Of course, there are times to question people’s character. Still, we often do it unwittingly that could be avoided. But how?

Elsewhere, you’ll find plenty of moral guidance that I find half-baked. For example, you’ll hear that you shouldn’t judge or make assumptions about people. You should always be kind, trusting, tolerant and giving.

That’s half-baked because the guidance is right about half of the time and in our guts we know it. We can’t or shouldn’t suspend all judgment. We will and should make assumptions about people. We can’t and shouldn’t always be kind, trusting, tolerant or giving – not to those who don’t deserve it.

So how can we minimize unnecessary drama, if not through half-baked moral guidance? I’d say through better understanding of how interaction works and how it goes wrong.

Here, then, is a step-by-step sketch of how drama tends to crop up in interactions with anyone – friends, partners, colleagues, relatives, etc.

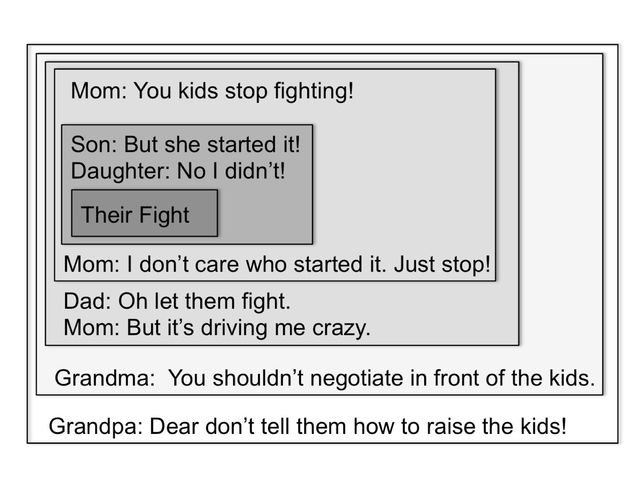

Conversations are multi-level. To track them, you need to be multi-level-headed: Read this family conversation top to bottom:

Notice how the dialog keeps upleveling to new topics, each about how the prior topic is being handled, for example, the mom talking about how the kids are fighting, the kids and dad talking about how the mom has intervened, and then the grandparents weighing in on the interventions. In the course of this short exchange there were five shifts of level – moves from talking, to talking about the talking, to talking about talking about the talking etc. Noticing such shifts will help you navigate them more efficiently.

Track the Forks in the Conversation: Any time conversation diverges from where you assume it’s going, you have three options: Steer it back to your topic, follow their topic, or call attention to the divergence. These three options form what I’ll call “the youmeus question” – Is the problem you, me or us? In answering the question, often unconsciously we think, “If the problem is you, I should steer it back my way. If the problem is me, I should follow you where you take it, and if the problem us, I should call attention to our divergence.

Words or Gestures: We call attention to the divergence through words (“Huh?” “Excuse me?!” “How did we get on that?”) or through gestures (balking, eyebrows raised, the weary sigh, a wary look, an impatient “ahem.”) Calling attention to the divergence uplevels the topic of conversation – talk about “how we’re talking.”

“The answer is you”: Calling attention to the divergence rarely happens without hinting that the problem is the other person. That’s understandable: You’re cruising one way and out of the blue they yank you another way, so it must be them. The trouble is that they feel the same: They perceive you as jerking it another way. The result is two parties that each think that the conversational thread is being jerked away from them.

Adding insinuation to injury: When turning attention toward the divergence, we tend to hint that there’s something wrong with the other person’s character. For example, if you raise your eyebrows at having the conversation diverted, it can easily be read as “what’s wrong with you?” even if you don’t mean it that way.

Tit for tat for two: Despite what folks say about turning the other cheek and an eye for an eye leaving the whole world blind, we all appreciate the need for self-defense. If someone provokes you, you have a right to defend yourself, tit for tat. But what if it’s unclear who started it? That’s what happens when we comment or gesture about a divergence. One person thinks “I was on track and, out of the blue, he yanked us to a different topic,” and the other thinks, “I was on track when, out of the blue, she sighed an impatient sigh as though there’s something wrong with me.” Both parties feel justified retaliating tit for tat.

Character contests: At any point in the dialogue diagrammed above, the uplevel could be taken as an attack on character, sparking an argument that escalates quickly, given how much we all depend on our positive self-regard. Such escalations can quickly max out as absurd winner-takes-all debates over which party is fundamentally flawed and which is, in effect, infallible. Though adults are generally subtler about it, it’s not uncommon for us to degenerate into “You’re stupid, you don’t know anything,” and “I know you are, but what am I?” high stakes competitions. Given the high stakes of character attacks, conversations can quickly become high drama, a winner-takes-all contest over which of you is fundamentally flawed and which of you is, in effect, flawless.

“I’ll give you space” vs. “You’re not worth talking to”: It’s hard to deescalate such character contests without implying that we’re claiming victory or admitting defeat.

Subjectivity masquerading as objectivity; Preference masquerading as moral imperative: In general, the bigger the conflict, the more we should caveat what we say by acknowledging our own subjectivity. For example, rather than saying “You’re being defensive,” we should say, “I think you’re being defensive.” But when the stakes get high, we tend to do just the opposite. Instead of talking about our impressions, we pretend we’re neutral judges. Instead of saying what we prefer, we talk about what people ought to do, as though we’re authorities on universal moral laws. This high-horse move tends to exacerbate debates.

Of course, most conversations don't go this dreadfully. So why even explore this dark scenario?

To prevent it: Understanding how conversations devolve into drama helps us avoid the subtle pitfalls at every step. And appreciating that the pitfalls are intrinsic features of human communication, we stop taking it all so personally.

The slippery slopes are inherent to the meeting and missing of minds. Noticing this, we’re not so quick to enter those nasty infallible character contests. So maybe we, our friends and our ex-friends aren’t so bad after all. People are just easily tripped up by the communication’s inherent tripwires. Often, it’s not you, me, or even us.

It’s it – the nature of communication itself.