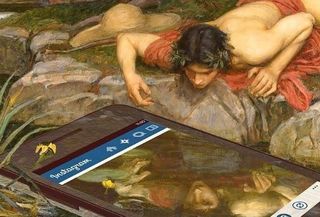

Trust

How Modern Life Made Us Angry

Research reveals key factors underlying political tension.

Posted January 24, 2019

Social trust has evaporated and political tensions continue to rise. Why are people so angry?

Our increased isolation and longing for connection seems to have led people to return to archaic tribalism based on political orientation.

You People Are All the Same

Democrats and Republicans have warped views of each other.

Take a study where researchers asked Americans to estimate the size of groups in each party. Respondents believed 31.7% of Democrats were members of the LGBT community. The actual number: 6.3%. As for Republicans, they believed that 38.2% earned over $250,000 per year. The actual number: 2.2%.

Part of this can be explained by the out-group homogeneity effect. Plainly, we tend to believe that members of our own groups are unique, while those in unfamiliar groups are the same. For the out-group, we generalize, we stereotype, and we denigrate.

For our in-group, we pay special attention to each member’s unique attributes, mental states, and contradictions. When we focus on group membership, we are more likely to strip people of their capacity to think and feel.

By painting an out-group with a broad brush, we reduce our burden of having to think of people as individuals. We default to our biases. It’s easier.

Perceptions, false or not, can determine reality. In this case, Americans are convinced that they are locked in a political grudge match against a homogeneous tribe of outsiders. A nationally representative study found that 20% of Democrats and 15% of Republicans believe that their country would be better off if large numbers of people in the other party died.

Parts of these changes are due to the reduction of “cross-cutting cleavages.” These are shared identities that are present in one social group but also in others. For example, rival fan bases of different sports teams will come together to support their nation’s Olympic team.

Political scientists have long held that the effects of partisanship are reduced by cross-cutting cleavages. Mutual social ties provide a sort of common ground from which political rivals can collaborate.

A wealthy Republican can find common ground with a working-class Democrat if they both attend the same church or community organizations. But the sorting of American social groups into two political tribes has reduced our cross-cutting ties.

Loneliness and Narcissism: Potential Factors?

Social psychologists Jean Twenge and W. Keith Campbell argued in The Narcissism Epidemic that American culture has experienced a decades-long shift towards narcissism. “By 2006," they wrote, "two-thirds of college students scored above the scale’s original 1979–85 sample average, a 30% increase in only two decades.”

Other research, however, has called this into question. A study led by Eunike Wetzel found that narcissism has declined slightly among college students since the 1990s to the present.

Still, many people feel alone. According to a survey of more than 20,000 Americans, 54% of respondents sometimes or always felt that no one knew them well. In fact, 56% felt that those around them were not “necessarily with them.”

In Britain, the statistics tell a similar story. In 2018, the Red Cross declared loneliness a “hidden epidemic,” with over 9 million Britons reporting that they often or always felt lonely. The severity of social isolation is such that Britain has appointed a “Minister of Loneliness.”

As economies grow and incomes rise, time becomes more valuable. Individualistic cultures prize accumulation of money over affiliation with community. This cultivates a time-is-money mindset. We want to make every moment count. And as The Economist points out, “when people see their time in terms of money, they often grow stingy with the former to maximize the latter.”

Without a tribe, we risk social isolation and a loss of self. As sociobiologist E. O. Wilson writes, “to be kept in solitude is to be kept in pain… a person’s membership in his group — his tribe — is a large part of his identity.”

The Collapse of Social Capital

According to political scientist Robert Putnam, social capital is "connections among individuals — social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them.” Broadly, social capital is a civic virtue based on a general trust in others. Goodwill, sympathy, fellowship; these are the properties of social capital.

Putnam has reported that voluntary organizations have experienced a large drop in membership. And it wasn’t that old members were dropping out. Rather, younger members were choosing not to join.

In 1975, American men and women attended 12 club meetings a year. By 1999, it dropped to five. In terms of hours per month, the average American’s investment in organizational life had fallen from 3.7 hours per month in 1965 to 2.3 in 1995.

This trend accelerated after 1985 as active involvement in community organizations fell by 45 percent. By this measure, nearly half of America’s civic infrastructure was obliterated in a decade.

Social capital collapsed.

For Putnam, community organizations generate social capital. They connect individuals and create trust. In this regard, civic institutions foment healthy tribalism based on voluntary association. Membership is contingent not on physical features but on personal interests.

But perhaps most importantly, civic institutions create cross-cutting cleavages. Members of formerly adversarial social groups can join together if both are members of the same voluntary association.

There has been a sharp decline in various forms of informal social engagement over the past 50 years. According to Putnam, visiting with friends, meals with family, and get-togethers at bars and nightclubs have decreased by 35%, 43%, and 45%, respectively. We’re growing increasingly unfamiliar with those around us.

Under these conditions, trust dissipates. We’re more biased when dealing with unfamiliar people. Sociologist Josh Morgan found that “the percentage of all respondents who said that most people can be trusted dropped from about 46 percent in 1972 to about 32 percent in 2012.”

For people to coexist, trust is required. And cross-cutting cleavages are essential for this.

Tribal Relapse

When we don’t have the time or interest to get to know one another, we may resort to cheap and easy methods of identification. We default to our biases about race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and sexual orientation.

The method is simple: “I trust this person because they look or think like me.”

The collapse of social capital provokes us to redirect our social energy elsewhere. What facilitates this drive to be among one’s “own people”? Research suggests that we automatically identify three features when we meet someone for the first time: age, sex, and race.

The first two make evolutionary sense. Our ancestors distinguished between old and young, male and female for the purposes of status, reproduction, and kinship. But race is different. Our ancestors traveled by foot and almost never encountered another tribe whose “race” differed from theirs.

Robert Kurzban and his colleagues suggest race is only important insofar as it signals group membership and familiarity. We typically use visual cues to determine who is from what tribe. In foraging societies, this might include hairstyles, piercings, and other adornments. As race is a salient feature, it signals tribal affiliations similar to how sports jerseys separate rival fan bases.

Or consider psychologist David Kelly’s work on in-group recognition among three-month-olds. As Paul Bloom writes, sharing Kelly’s findings, “Ethiopian babies prefer to look at Ethiopian faces rather than Caucasian faces; Chinese babies prefer to look at Chinese faces rather than Caucasian or African faces.” At an early age, then, we attribute value to familiarity. To be clear, babies adopted by parents of a different race prefer to look at faces that resemble the race of their adoptive parents. It’s not about race, but familiarity. We have an ingrained preference for what we easily recognize. And spending less time with people who are different from us leads us to treat them as outsiders.

Eliminating the Out-group

The Republican and Democratic mega-identities could be a consequence of our return to archaic tribalism that prioritizes salient features over political or civic values. Political observers have referred to this as “identity politics,” a seemingly new phenomenon. But that’s not actually true.

As Jonah Goldberg contends, “‘Identity politics’ may be a modern term, but it is an ancient idea. Embracing it is not a step forward but a retreat to the past.”

Looking beyond visible traits and treating others as individuals is a relatively recent idea. But we often fall short of actually doing it. We group individuals together based on their superficial characteristics. This comes easily to us. And when something comes easily, we will find all kinds of reasons to justify why it’s right.

We are now in the position of moving back toward this way of thinking, of folding people into categories. We want to easily understand who our allies and enemies are. The desire for an out-group is ever present. Today, the safest way to express this desire is through political parties. Unfortunately, one of the surest ways to obtain social status in our in-groups is to denigrate our out-groups.

So we have a choice: We can repair our country by engaging with those with whom we politically disagree. Or we can denigrate our political opponents to boost our social status at the cost of tearing the country apart.

There’s another way to eliminate your out-group: make them your in-group by finding shared values. We must create new cross-cutting ties.

A version of this post was published on Quillette.