Health

Understanding Intersectionality in Health Psychology

How health psychologists of color can shape the future of health care.

Posted April 12, 2019

Contributing Author: Darryl Sweeper, Jr, MA

Editor: Natalie A Cort, PhD

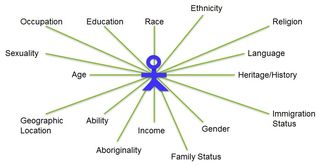

For decades, psychological researchers have explored the ways our health is impacted by our race/ethnicity, gender, gender identity, socioeconomic class and sexual orientation (Novotney, 2010). However, until recently, there has been relatively limited purposeful examination of "...how social categories intersect and work together to affect an individual’s lived experience, or what social scientists now call intersectionality" (Banks & Kohn-Wood, 2002; Novotney, 2010, p. 1). As the country’s diversity increases, health psychologists are uniquely positioned to unveil blind spots in the psychological field and spotlight the interplay of multiple social identities and health conditions.

Intersectionality is not a new concept, although it has been a buzz word for the past several years. The seminal promoters of intersectionality, The Combahee River Collective (1977/1995), a group of Black feminists lesbians, were instrumental in highlighting that the White feminist movement was not addressing their particular needs. They contended, “We...find it difficult to separate race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously” (Combahee River Collective, 1977/1995, p. 234). The term intersectionality then found its way into research in the early work of Black feminist scholars (Collins, 1990; Crenshaw, 1989, Hooks, 1990). It was noted that intersectionality “moves beyond single or typically favored categories of analysis (e.g., race, gender, class, sex) to consider simultaneous interactions between different aspects of social identity…as well as the impact of systems and processes of oppression and domination” (Hankivsky & Cormier, 2009, p. 3).

What the heck am I talking about?

More often than not, the psychological and medical fields fail to take into consideration the person as a whole—instead primarily focusing on the specific ailment in need of treatment. Thus, increased appreciation of intersectionality is essential as we provide care to our patients. For instance, when treating Black men who are cancer survivors or a Black transgender woman with an opioid use disorder, we are faced with complex and interconnected needs to be considered in treatment planning. Yes, there are evidence-based treatments for the psychosocial sequelae of cancer as well as substance use disorders. However, those treatments generally fail to cater to the nuanced experiences of such patients with unique needs.

Why does this matter so much to health psychology?

Health psychology is a growing subfield of psychology which focuses on the emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and social factors that affect a person’s physical well-being. Health psychologists are devoted to exploring and understanding how psychological experiences impact how people stay healthy, why they become ill, and how they respond to illness. Therefore, by focusing on health promotion, prevention, and treatment, health psychologists are instrumental in creating successful outcomes by considering intersectionality.

According to Dr. Linda Brown (Novotney, 2010, p. 1), merely "taking time to examine the interactive effects of each aspect of a patient’s identity—be it his or her or their gender, sexual orientation, social class, or race—will help practitioners understand how each patient’s experience has shaped their behavior" and the behaviors of those around them. Such deliberate inclusion transcends representation, offering the possibility to repair misconceptions perpetuated by the invisibility of minority groups and the marginalized subgroups within them. However, to understand better how these categories of identity are contingent on one another for meaning and how they are jointly associated with outcomes, scholarly attention needs to reconsider focusing on arriving at a contextualized understanding of the unique experience of groups, as opposed to observing them in comparison to how they depart from norms based on dominant groups (Cole, 2009).

Lisa Rosenthal (2016) suggests that to respond effectively to intersectionality, we must (a) be trained using social justice curricula, (b) address and critique oppressive societal structures, (c) attend to patients’ resilience as well as resistance, (d) engage and collaborate with diverse communities, and (e) work together and build coalitions, including with allies. Health psychologists of color may be uniquely attuned to—and insightful about—intersectionality and therefore may be more comfortable in engaging in social justice advocacy. As the field of psychology diversifies, welcoming more mental health professionals who are from marginalized groups (such as LGBT+, men of color, and immigrants), the field may be forced to move beyond the practice of treating the symptoms of a disorder without consideration of patients' multiple and intersecting cultural identities.

References

Banks, K. H., & Kohn-Wood, L. P. (2002). Gender, ethnicity and depression: Intersectionality in mental health research with African American women. African American Research Perspectives, 174.

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American psychologist, 64(3), 170.

Combahee River Collective. (1995). Combahee River Collective statement. In B. Guy-Sheftall (Ed.), Words of fire: An anthology of African American feminist thought (pp. 232–240). New York, NY: New Press. (Original work published 1977).

Hooks, b. (1989). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. Boston, MA: Sound End Press.

Rosenthal, L. (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. American Psychologist, 71(6), 474.