Beauty

Imagine a World Without Museums

The museum ranks among the greatest human concepts of all time

Posted July 3, 2021 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Great museums offer us transcendent moments of connection to the entire human story and all the universe.

- Museums—large and small, good and bad—teach us important things about ourselves.

What are museums? Glorified bank vaults for expired trinkets and dusty novelties? Ostentatious tourist traps? Convenient excuses for kids to take fieldtrips? How about one our most important ideas ever?

What would the world look like without museums? Nowhere to go and see a real T-Rex tooth, lunar module, or bog people. Museums matter because they are invaluable points of collection and contemplation for a species with a complicated past and self-awareness issues. Somewhere in their wonderful mix of beauty, fact, fiction, lies, and error we discover crucial truths about us. As such, museums are invaluable gateways into our shared humanity.

Making a Statement. Museums are modern elaborate versions of those striking prehistoric hands stenciled on cave walls by people who lived tens of thousands of years ago or that plaque from Earth placed on the moon in the summer of 1969. Museums scream to every visitor: “Look at all this stuff! People were here. People figured things out. We did things. And you are part of it!”

A single life might be fleeting, but a great museum can connect us to the wonders and richness of everything. I exited the Hayden Planetarium (Rose Center for Earth and Space, New York City), for example, feeling energized, larger even, because I had been reminded on an emotional level that home is a lot more than one lonely spheroid spec spinning in the dark.

Thoughtful exhibits give us tangible evidence of our collective accomplishments, of purpose, meaning, vulnerability, mistakes, failures—our humanness. I once peered into the vision slit of an ancient hoplite helmet and for a moment felt the stare of a human face looking back at me from more than 2,000 years ago. I imagined the extremes of courage, fear, pain, rage, and triumph that might have once occupied that bronze time capsule of human conflict. This kind of experience is common in museums. One exhibit, even a single artifact, can hold transcendent powers capable of transporting us across vast distances in time and space.

The First Museum. Depending on how we define it, the museum concept is at least three or four centuries old. But I would argue that it goes back much further. If we consider a museum to be a place where people can view collections of things considered to have some kind of value or interest, then I can easily imagine the first museum having existed a million or more years ago.

Picture an elderly Homo erectus proudly displaying an assortment of exquisitely crafted Acheulian hand axes for all to see. Maybe there was even a children’s educational section for hands-on tool making fun. For as long as humans have had stuff, someone probably felt compelled to show off that stuff.

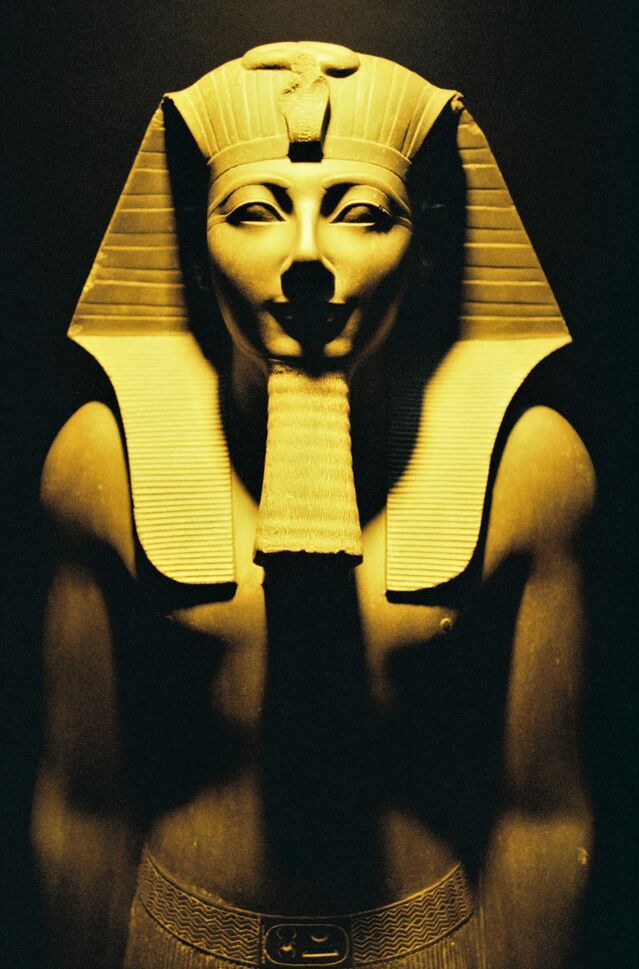

Enormous museums such as the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum and Britain’s Natural History Museum may get most of the attention, but the little ones have a lot to say, too. Luxor Museum in Egypt, for example, houses a small but unforgettable collection of artifacts bathed in delicate lighting so effectively that a visit can be a hypnotic experience. Pound-for-pound, that museum might be the world’s best.

But even bad museums can have value. The Creation Museum (Kentucky, USA), for example, may be a vulgar monument to pseudoscience and deception, but it can teach us important things about American culture and humankind in general. I visited museums in a couple of communist countries that were like supervolcanoes of absurd propaganda. But they made me think more about patriotism and the national mythologies of all countries.

Museums are not lifeless snapshots of the past but something closer to living evolving organisms. Similar to natural selection, they are subject to pressures from their society’s changing knowledge base, values and perspectives.

Many people today would be horrified by the overtly sexist, racist, nationalistic, scientifically/historically incorrect, and ethnocentric exhibits that were common in the past. People who look back from the vantage point of the 22nd century will no doubt find much of the content in today’s museum’s wrong and disturbing.

The evil that men do. It has been more than twenty years since I visited Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust museum and memorial. Nevertheless, some of the weight and darkness I experienced there remains in me. I am not Jewish, but I felt deep pain and sorrow that day. I am not a Nazi, but I felt a biting guilt.

Some museum exhibits may serve as public confessionals or secular altars, places where visitors can learn about, pay respects, and suffer a brief taste of the various horrors we so often inflict on one another. Done well, they whisper the warning that perhaps our most important challenge is to accept that every one of us carries the potential to be “the monster” and the ultimate struggle is to change ourselves before we self-destruct. (Did I mention the foreboding Ground Zero Theater at the National Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas?)

Some museums are blatant trophy rooms designed to show off only the best of ourselves. This is a good thing, too. We need it. A great art museum, for example, reassures me that, no matter what comes, humankind has not been a total waste of atoms.

Spending a day inside an ornate palace of emotion such as the Louvre or Metropolitan Museum of Art is proof that even the worst of our wars, oppression, and neglect cannot erase the beauty we humans routinely conjure out of thin air. We may hate, but we love, too. Destroyers and creators, that’s us.

To date, I have visited museums in more than 30 countries on six continents and sampled widely along the spectrum: large, small, exciting, confusing, immaculate, dirty, profound, weird, dishonest, otherworldly, and more. I value them all because every museum is a part of the human epic. They help us define Homo sapiens.

From the overwhelming American Museum of Natural History in New York City to the charming and efficient Cayman Islands National Museum in Georgetown, Grand Cayman, they matter. Religious people have their holy sites, music lovers their concert halls, and sports fans their stadiums. For me, however, it is those exceptional buildings around the world dedicated to preserving the human past, spreading scientific knowledge, and sparking inspiration. Museums are my cathedrals, their artifacts my sacred relics.

Visit museums. Support museums. Love museums. They are our necessary reflections in the mirror, the biased but revelatory autobiographies of a species still seeking to know itself. We need them.