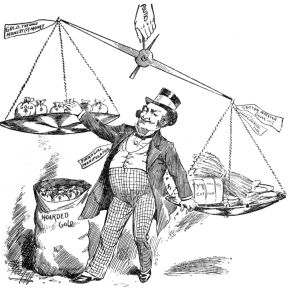

Hoarding

With popular reality shows like Hoarders and Hoarding: Buried Alive, this problem has come into great focus. The viewer peeks into the lives of people who are overwhelmed with belongings; every room of a hoarder's house contains mountains of clutter, garbage, and junk that the average person would easily toss. The spectrum from clutter to hoarding is wide, but people can become emotionally attached to their piles of stuff, not willing or able to let anything go.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, 2 to 6 percent of the U.S. population suffers from hoarding. The tendency to gather and hold onto items can appear as early as one’s adolescent years, often worsening with age. A serious case can result in poor health and safety concerns, and the person who suffers can also develop poor personal hygiene.

There are known risk factors such as experiencing a traumatic event; persistent difficulty making decisions; and having a family member who also hoards. Individuals who have both OCD and hoarding symptoms were more likely to have experienced at least one traumatic life event in comparison to those with OCD alone. The obsessive need to collect and keep material objects may be a way for these sufferers to cope.

• Persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of actual value.

• Emotional distress over parting with possessions.

• Allowing possessions to accumulate to the point of congesting living space, often requiring intervention by others.

• Allowing hoarding to interfere with day-to-day life, including work or relationships with friends or family.

• Hoarding cannot be better explained by another mental disorder such as brain injury, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or major mental illness

Signs of hoarding behavior can be seen in adolescence, and sometimes in children as young as 6 or 7 years of age. These children are not able to function in their living space, with beds, desks, and closets spilling over with belongings. The difference between hoarding and garden-variety messiness is the emotional reaction they have when they are forced to part with their possessions. Children who hoard feel violated, anxious, and distressed. They also deem their seemingly useless items as valuable, and categorize them for sentimental reasons. I found this bird feather the day I went to the playground. If hoarding is not addressed, it will likely worsen as the child ages.

Sometimes, these possessions take on high attachment value, sometimes even greater than the attachment assigned to the people close to them. In fact, people who hoard will often choose their possessions over friends and family. When throwing out possessions, some sufferers experience intense emotions that are comparable to those experienced when a loved one is lost.

Accumulating belongings may fill an emotional hole left by trauma; it allows individuals to avoid dealing with their pain. Many people who hoard describe a rush when acquiring new items, especially if the item is free or considered a bargain; and these individuals go to great lengths to justify their collections when questioned by others. If a family member or friend removes these belongings without the person’s permission, the person feels violated and anxiety may be triggered.

One study asked participants to make decisions about keeping or chucking items, some belonged to them or some did not belong to them. Researchers found abnormal activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula of the brain, known for decision-making and risk assessment. The people who hoard are unable to make decisions about discarding the items they own.

It is unclear whether hoarding is due to heredity or environment. But half of the people who hoard have a family member who hoards. And there is evidence that links compulsive hoarding to a region on chromosome 14—which has also been linked to disorders such as Alzheimer's and other cognitive impairments.

Hoarding is a type of compulsion, and it’s estimated that about one in four people with OCD also compulsively hoard. It is also related to obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, as well as anxiety and depression.

Research from the University of New South Wales has found a link between hoarding behavior and traumatic events, such as loss of a spouse or loss from a natural disaster. People traumatized by such events may show signs of hoarding symptoms at the time of the event or shortly thereafter.

If a person has attention deficit disorder, ADD or ADHD, it does not mean that they have compulsive hoarding behaviors. The disorganization of a person with ADHD or ADD is not related to hoarding. However, a person who hoards may also have or develop attention deficit. And a person who has attention deficit may be at risk of developing hoarding as well.

A person who hoards does not have to be a compulsive consumer, though such shoppers can hoard. Compulsive buyers often purchase items on impulse, these are acquisitions that the person can do without. Spending without adequate reflection can result in storing unopened items in closets as the cycle of buying is perpetuated. As belongings accumulate over time, compulsive buyers may eventually develop a hoarding habit. The relentless shopper generally tries to conceal their habits, whereas the person who hoards does not.

Research shows that the decision-making process of a person who hoards is seriously compromised. Neuroimaging studies have revealed common traits among people who hoard; this includes having severe emotional attachments to inanimate objects and extreme anxiety when making decisions, even simple ones. A person who hoards finds it gut-wrenching to make the decision of tossing a piece of garbage like a plastic bag, for example.

Compulsive hoarding is more common in older adults, and it may be more common in men than in women. When compared with adults between the ages of 33 and 44, older people between the ages of 55 and 94 are three times more likely to have this compulsion.

Jamie Feusner at UCLA’s School of Medicine notes that many of these people are single, either because their behavior has driven away those around them or has prevented them from forming meaningful relationships.

A person with compulsive hoarding is not "lazy" about cleaning or organizing their home. For a person with this compulsion, throwing away a paper cup may be dreadfully difficult and stressful. And for such a person, throwing away five cups may require immense courage and hard work. This is not related to messiness.

Animal hoarders have more animals than they can properly care for, but they don’t recognize that there is a problem and they typically continue to adopt more animals. While cats are most commonly hoarded, dogs and other animals are hoarded as well. The health of these animals is often compromised, they may have parasites, poor nutrition, and untreated infectious diseases. The animal hoarder is normally unable to keep up with waste clean-up either. The household becomes so untenable that animal control services as well as law enforcement are often called upon.

Unlike hoarding, collecting has a social aspect. Collectors are proud of what they collect. The collector preserves and maintains these items, giving the collector pleasure; they display the items and show them to people who may also appreciate them. The person who hoards is more haphazard when they acquire things, often they feel an item might be needed in the future.

Commonly hoarded items can include anything to everything. But whatever it is, the person who hoards assigns value to their items. Such a household can contain objects including paper and plastic bags, cardboard boxes, newspapers, magazines, photographs, household supplies, old food, unused clothing, sports gear, broken appliances. Just about anything can be stockpiled.

The person who hoards also impacts the lives of the people around them. A house can, in fact, become so compromised that it turns into a clear fire hazard or toxic waste site. People with severe hoarding may even find child services and law enforcement at their door.

This disorder is hard to treat. While medication does not appear to reduce the behavior, it may help to reduce symptoms. Medications that treat conditions like depression and anxiety are helpful in about a third of cases. Therapy can help. Randy Frost, a professor of psychology at Smith College and the father of hoarding psychology, along with colleagues, came up with a cognitive-behavioral approach for hoarders. He includes in this therapy: Ask the person who hoards to try throwing away an item as an experiment. Not as a broad policy, but as a small trial. Then the therapist monitors how the sufferer progresses.

Look for support in the form of a clutter buddy or coach. The person should be respectful, compassionate, and have integrity, and would never try to sneak your belongings away. A good clutter buddy has good personal boundaries, and will not try to influence you with their values and beliefs. They may offer you what they have learned about themselves from experience, which is not the same as trying to apply their opinions into your life.

You cannot clean up for a person who hoards. To help this person, you should not interpret their needs and willingness as noncompliance. They will make their decisions when they are able. Do not interpret their readiness or lack thereof as being unmotivated, lazy, difficult, or unappreciative of your efforts. Understand and accept the person who hoards as who they are.