When Safety Is Shattered

Why losing a home is uniquely painful—and how we can all better appreciate the space we inhabit.

By Abigail Fagan published January 5, 2021 - last reviewed on February 21, 2022

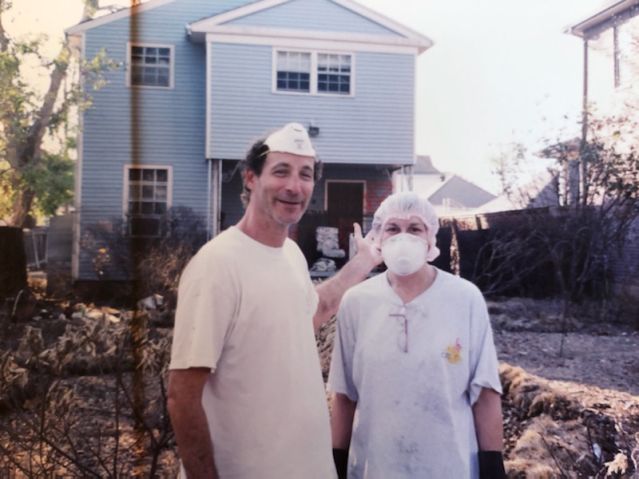

Rita and Terry Rowan moved into their home in Santa Rosa, California in 2010. The house had four bedrooms to host their children and grandchildren, and a beautiful yard with silver birch trees, sloping hills, and a stone patio overlooking the mountains.

But in 2017, the Rowans confronted the California wildfires raging through the state. They previously lived in San Diego and survived two fires with their house intact. So when the wildfires barreled toward their new home that October, Terry was determined to fight the blaze. “I didn’t think this house would burn,” Terry says. “We just did not believe it was going to happen.”

As the fire moved closer and the electricity sputtered, Rita knew they had to leave. She grabbed the dog and dog food. She snatched coats from the front closet and paintings from the wall as she ran out the door. Terry was still adamant about fighting the fire, so they quickly decided on a meeting place and Rita begged Terry to leave if he thought the effort was futile.

Embers rained down on the house and hit the roof like hail, Terry says. His tiny garden hose looked absurd in the massive blaze. The embers descended on homes and trees, instantly engulfing in flames. Choking on smoke, Terry rushed to his car and fled. He met Rita and the two slept in the car. In the morning they drove to a family member’s house to figure out what came next.

Five days later, the Rowans returned to the land on which their home had sat. The family raked through the debris to find anything that could be salvaged—old family photos or childhood mementos. The family then stood in a circle, linked arms, and recited the Mourner’s Kaddish, the Jewish prayer that marks the death of a loved one.

Terry and Rita’s experience is not uncommon. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent flood damaged or destroyed 800,000 homes. In 2017, Hurricane Maria ruined 70,000 homes and damaged 300,000. In 2018, California fires gutted more than 17,000 homes. The 2020 California wildfire season, marked by apocalyptic orange skies, has burned an unprecedented 4 million acres of land, decimating at least 8,200 structures and displacing more than 53,000 people.

The tragedy of lost property, of course, pales in comparison to the loss of life in each disaster. But losing a home is still devastating—and due to climate change, it’s a loss that more and more people are forced to endure. The experience is uniquely painful—but understanding it can help everyone better value the space that they create.

What Is a Home?

A home is where we store our belongings, invite friends for meals, fall asleep each night, and share moments of laughter and tears, silence and intimacy. As the vessel for so many facets of life, what psychological role does this structure play?

“A home is our shell, our sense of place, and our sense of identity,” says Charles Figley, Chair in Disaster Mental Health at Tulane University. It holds experiences, stores memories, and evokes contemplation. It’s a reprieve from the chaos of the world, providing a sense of security.

Pioneering psychologist Abraham Maslow developed an influential model of human motivation conceived as a hierarchy of needs. At the base of the pyramid lies physiological needs, to simply breathe, eat, and sleep. Once those needs are met, people are motivated to secure safety. Next comes love and belonging, esteem, and finally, self-actualization. Without meeting the needs at the base of the pyramid, such as shelter, people aren’t equipped to progress toward meaning and fulfillment.

“The loss of a home is damaging to the sense that you can go on to be productive and accomplish your goals, because you don't have a place where you can take care of your own body,” says Frances Boulon, a psychologist at the University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras. “It's a devastating experience.”

The safety of home is even wrapped into our biology. In our evolutionary past, humans felt safe when another person or dog was keeping watch, allowing the body to switch from a vigilant state to a calm one, says Stephen Porges, Distinguished University Scientist at Indiana University. Today, the home is the physical structure where we feel safe enough to fall asleep, eat and digest, and be intimate with others. Without it, the body enters that threatened state, leading to the possibility of a destabilized nervous system and resulting symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, or depression. Says Porges: “For most people, the home is a metaphor of embodied safety.”

Waves of Change

Losing one’s home can shatter fundamental assumptions about the world. People may no longer believe that the world is a safe place, that they have control, that they can achieve their goals, says Russell Jones, a professor of psychology at Virginia Tech. In addition to a global perspective shift, there are social, financial, and environmental changes.

Socially, a family might be uprooted from their friends, school, and community at the time they most need social support. Financially, people may have worked for decades to pay off a mortgage and pass the home down to their children, but that financial security and family legacy disappear, says Ethan Raker, a doctoral candidate in sociology at Harvard University. Renters and low income people may struggle to survive the financial blow, and obtaining federal assistance can be a bureaucratic nightmare.

People’s relationship with the environment can change as well. On a personal level, people’s livelihood may have depended on land that was destroyed. Or it may alter their relationship with nature. “You no longer see trees or brush as you’re driving along. You see a thing called fuel,” Terry Rowan says. On an existential level, natural disasters can instill fear and helplessness around climate change and a broken relationship between the land and the people. “There’s ecological grief in this community about our land, which has been inhospitable to us for three years in a row,” says Adrienne Heinz, a therapist and a research scientist at the National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder at the Palo Alto VA Health Care System and Stanford University.

People may also be forced to make huge decisions in the aftermath, says Doreen Van Leeuwen, a marriage and family therapist in California. While unmoored from their life path, they must ask: Do I want to rebuild? Do I want to move? Do I need to relocate to another city?

“What’s important about home is it’s a place where you don’t have to justify your existence, where your welcome doesn’t grow thin,” says psychologist Kenneth Miller, who studies and treats refugees' mental health, many of whom have been displaced for years. Yet most people around the globe never stop to appreciate the comfort, stability, and happiness that comes with simply having a home. “When you’re sick, you probably aren’t walking around thinking, ‘It’s nice to be well!’” Miller jokes. But it’s actually worth doing just that. A growing body of evidence shows that practicing gratitude can benefit mental health and happiness. “I finish my meditation practice by naming five things I’m grateful for that evening. One of the things I find I often do is look around my home,” Miller says. “It’s grounding.”

The Power of Possessions

For all of the focus on minimalism and “Marie Kondo-ing” your space, there are many possessions that do, truly, spark joy. “Possessions have a magical quality for all of us,” says Randy Frost, a psychology professor at Smith College. “If you think about a ticket stub that you save from a favorite concert, nothing about the physical properties makes it special. What makes it special is its association with the event in your mind. Seeing the stub brings the event back to life.” This is how we form emotional attachments to objects. The possessions we keep embody memories, relationships, and pieces of our identities. They frame personal history and family history. They’re part of being alive and appreciating life.

The possessions that evoke the most pain and grief when lost are irreplaceable—old family photos, birthday cards, a childhood trophy or professional award. “The 1957 Chevy that was passed down from your dad? That cannot be replaced, and it brings a real sense of distress. You never get it back,” Jones says.

Rita and Terry Rowan had kept all of their son’s mementos in their garage—photos, videos, projects, anything that marked an accomplishment. They all vanished in the fire. “I felt like we lost our son’s childhood,” Rita says. They also lost the items that represented their own work, achievements, and family history. “Terry had dozens of track medals. All gone. We had beautiful letters from our former students. All gone. My great grandfather’s samovar, which traveled from Russia to Argentina to Brooklyn. It wasn’t a fortune, but it was family history,” Rita says.

Recognizing the power of items like Rita’s samovar reveals how everyone can better appreciate their belongings. People can feel comfortable decluttering or avoiding new purchases that aren’t meaningful. But people can feel secure keeping sentimental items and embracing their ability to resurrect memories and depict identity. Those possessions can go further, by activating and continuing to build your identity. When you slip on the dress that you and your best friend bought on a trip to Mexico, call her to reminisce or plan a new adventure. When you spot the Green Day ticket stub wedged into your mirror, think about the next concert you want to attend. Research shows that experiences and activities often provide greater happiness than acquiring possessions, Frost explains, so embrace the opportunity for a possession to spur you to action.

A Toll on Mental Health

Many people follow a similar trajectory after losing a home, says therapist Wendy Wheelwright. After the initial shock, individuals and communities spring into action, experience an outpouring of support, kindness, and generosity, and emerge determined: We’re going to get through this.

Around six months later, however, reality hits—often marked by logistical stress. People may realize that insurance coverage falls short, struggle to inventory every item, or recognize that the process will take longer than they imagined. “Survivors are really busy people. Now they’re experts on insurance coverage, geo-permits, and septic tanks. They don’t have time to feel the pain,” Wheelwright says. Cognitive resources can become depleted, leading to stress and irritability. “Imagine calling the cable company once? That’s a nightmare,” Heinz says. “Now that’s your whole life.” At this point, distress can emerge through physical or psychological symptoms: insomnia, headaches, stomachaches, drinking, trouble concentrating.

Susan Levin lost her home when the levees broke and unleashed a tremendous flood in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. The home was one she purchased with her husband the year after they were married. They lived there for 25 years, raising their two daughters, and opening an athletic shoe store, which became a staple in the community. Levin’s evacuation story wound through family members’ homes, FEMA trailers, and rented rooms. She struggled with irritability, panic, and post-traumatic stress, particularly around continually moving and inhabiting small spaces. At one point she found herself gasping for air; subsequent medical appointments signaled she was suffering from claustrophobia and post-traumatic stress. A particular mark of that time lingers today. In the beds she slept in during that time, her feet hung over the edge. Now, she never lets her feet touch the foot of a bed.

Only a small portion of trauma survivors, around 10 percent, go on to develop PTSD. Still, PTSD and depression are the two most common conditions that develop after the trauma of losing a home, Russel Jones says. One study surveyed survivors of the Kobe Earthquake, which struck Japan in 1995. Sixteen years later, housing damage was still associated with lower life satisfaction and lower health, even when controlling for socioeconomic status. Another study assessed 725 survivors of the 1988 Spitak earthquake in Armenia 23 years later. Receiving housing assistance in the first two years after the disaster was linked to a lower likelihood of PTSD years later, underscoring the importance of government programs to help people after these ordeals.

After the California wildfires, Sonoma County created the app Sonoma Rises to address the mental health of the community. The program, Van Leeuwen explains, provided mental health services, drop-in centers, art therapy, and skills for psychological resilience. After Hurricane Maria, Domingo Marques, of Albizu University in Puerto Rico, developed community mental health programs based on cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy. He practiced and taught psychological first aid and recorded YouTube videos demonstrating mindfulness and breathing techniques.

Survivors of home loss may also experience post-traumatic growth—positive changes that sometimes emerge after a trauma, such as developing a greater appreciation for life, embracing new opportunities, forging stronger relationships, exploring religion and spirituality, and appreciating one’s inner strength. In a study of 44 children and adolescents whose homes caught fire, Russell Jones identified post-traumatic growth as one of five key themes. As one teen recalled, “I learned so much from this. Like, not to take anything for granted. I mean, to see all these people do all this stuff, like the Walkathon, the pep rallies, it was just amazing.” Post-traumatic growth serves as a reminder that profound reflection and growth is always possible.

Gender Dynamics

The experience of home loss can be different for women and men. If a woman had taken more ownership of the home—perhaps she decorated her children’s bedrooms, maintained family photo albums, and hosted meals for the holidays—the loss may be more poignant. “Women tend to be more focused on the nitty-gritty of child rearing. They can be traumatized when their nest is destroyed,” Figley says. Women are also likely to keep family memorabilia, says Michelle Meyer, Director and Assistant Professor of Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center at Texas A&M University. “They’re keeping the historical legacy alive. When the home is damaged or destroyed, it rocks that connection.”

Men are often focused on the need to get a roof over the family’s head and get back to work to provide for them, Meyer says. They may want to “get back to normal” while women may contemplate whether they really can find a new normal in the same place, Meyer says. Women are more likely to talk about their grief and lean on their friends for support. Men, who may feel pressure to be strong and provide for the family, may repress the emotional impact—which can emerge later through physical symptoms such as insomnia or nervous breakdowns, Heinz says.

These differences manifested in Susan Levin’s experience. Levin recalls feeling upset, impatient, and pessimistic in the aftermath while her husband was determined and proactive, jumping on the phone with FEMA and the insurance company, handling logistics, and trying to make progress. “I went down and he went up,” Levin recalls. “He was a rock.”

Since a husband and wife may experience and process the loss differently, a wedge can form between them, Figley says. Processing the loss together can solve that problem. “I always encourage people to go to counseling as a couple,” Figley says. “I want them to talk to each other, not me.

Moving Forward

A few practices are pivotal in helping to overcome the loss of a home. The first is for individuals to allow themselves to grieve. Feeling those emotions fully, rather than denying them or believing they “shouldn’t” feel them, will allow them to move forward. The second is social support—sharing experiences and emotions with a trusted loved one can help process the experience. Mental health struggles often make people want to turn inward, but it’s exactly when they need to turn outward, Heinz says. The third is disaster preparedness. People can digitize photos, store paperwork in the cloud and on flash drives, put important records in a safe deposit box, and develop evacuation checklists based on the amount of time they have to leave, Heinz says, which can provide practical and psychological benefits.

The fourth practice is to put down roots. Being severed from one’s life can lead to feeling adrift and untethered, so survivors can get involved in a volunteer organization, book group, church, or a child’s school. Becoming involved and maintaining family traditions can allow people to envision a new future and create new memories, Boulon says. Instituting traditions allows people to reclaim a sense of who they are—by lighting candles at dinner or watching a movie every Friday night.

The fifth practice is to find meaning. A natural disaster can strip people of their sense of control—which is often explored in therapy. “There’s a point when someone decides what the tragedy means,” Jones says. “And that question is revisited with time. A year later, you might say, ‘What do I appreciate differently about the world?’”

Lastly, survivors simply need to take care of themselves. When they’re on the phone with insurance all day, it can be hard to find time to exercise, speak with a therapist, or just relax. But carving out time for self-care will better equip them to handle the situation long-term. Hobbies are also helpful, such as gardening or barbecuing, Van Leeuwen says. In addition to providing joy, they allow people to express a part of their identity at a moment when they don’t feel grounded.

Her passion for gardening was just what Susan Levin turned to when her family found a new home in Louisiana. She had always loved to garden, and her old home boasted a luscious tangle of bushes and flowers. When she and her husband settled into their new house, a moment of peace came one Sunday morning when she stuck her shovel into the earth outside her front door. She began to plant a new garden, ready to see what would grow.