Selfies, Filters, and Snapchat Dysmorphia: How Photo-Editing Harms Body Image

Cosmetic surgeons are prime witnesses to the assault of photo-editing on body image and self-esteem.

By Abigail Fagan published February 7, 2020 - last reviewed on November 28, 2020

When Maya* first downloaded Instagram, at age 18, she felt confident in her appearance both on and off screen. “I wouldn’t think twice before posting a selfie,” she recalls.

As she spent more time on the platform, she watched trendy influencers or friends at university post perfect photo after perfect photo. The pristine images began to make her feel anxious and insecure: Did her nose look small enough? Was her chin defined? Why didn’t she look like those effortlessly beautiful influencers? “I kept ruminating over the same things,” Maya says. “It ran me down.”

To salvage her self-esteem, she downloaded the popular photo-editing app FaceTune. With a pinch of her fingers she plumped her top lip, shrunk the tip of her nose, and sharpened her jawline. But not too much. She didn’t want the doctored photos to diverge too far from her real appearance. “You feel kind of stupid if you don’t look like your Instagram in your real life—so you try to achieve in real life how you look in your Instagram,” Maya explains.

To bridge that gap, she explored cosmetic surgery. She also looked into dermal fillers, injections that plump features and smooth wrinkles. Five days before her 21st birthday, she walked into her doctor’s office armed with edited selfies, and had her lips and chin injected with fillers. When she turned to the mirror, she was thrilled. “It was amazing. It was kind of like I had a filter on my face,” Maya says. “I felt completely confident.” At her birthday party a few days later, she snapped photos of the celebration to share. “I didn’t edit any of my photos,” she says. “There was no need to.”

New Beauty Standards

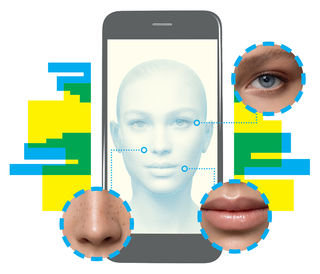

Physicians who work at the aesthetic edge are witnessing a shift: Photo-editing is driving clients to redesign themselves. People historically came to cosmetic surgeons with photos of celebrities whose features they hoped to emulate. Now, they’re coming with edited selfies. They want to bring to life the version of themselves that they curate through apps like FaceTune and Snapchat.

“People can take a photo of themselves and, in an instant, manipulate it. That makes a change feel more real and attainable,” says Boston University cosmetic surgeon Neelam Vashi.

Cosmetic enhancement has surged in recent years. The number of minimally invasive procedures tripled between 2000 and 2018, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Nearly 18 million surgical or minimally invasive procedures were done in 2018, up from 15 million in 2013. In 2015, 42 percent of cosmetic surgeons reported seeing clients whose goal was to improve their appearance in selfies. In 2017, that number rose to 55 percent.

British plastic surgeon Tijion Esho dubbed the concept “Snapchat Dysmorphia,” and the term took off when Vashi and her colleagues declared in JAMA Plastic Facial Surgery that selfies and photo-editing had instilled new beauty standards. “It can be argued that these apps are making us lose touch with reality because we expect to look perfectly primped and filtered in real life,” the authors wrote. And knowing that an image is doctored doesn’t stop your brain from engaging in comparison. It happens automatically, says Renee Engeln, a psychology professor at Northwestern University and the author of Beauty Sick: How the Cultural Obsession with Appearance Hurts Girls and Women.

Society and scholars have been grappling with unrealistic beauty ideals forever. What makes photo-editing different? In the past, those ideals were propagated by celebrities. We can grasp that those standards are unattainable because of the colossal distance between stars and everyday people; celebrity, after all, is defined by a professional commitment to appearance through regimented exercise, controlled diet, and a team of makeup, hair, and fashion experts.

But now that gap is narrowing, if not outright disappearing. FaceTune and other editing applications are so widely available that unrealistic beauty ideals are invoked by classmates, coworkers, neighbors, and friends.

The endless reel of flawless faces can consume time and energy. It can erode self-esteem. And it can drive a wedge between the self posted online and the self reflected in the mirror—one’s ideal and one’s real self. “It’s devastating when those two versions don’t line up,” Engeln says.

An article published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders found that the more adolescent girls engaged in photo-editing, the more they worried about their body and dieting. “You get a mismatch between how you perceive yourself and the images you see on social media. That increases body dissatisfaction,” says study author Susan Paxton, a professor emeritus at La Trobe University in Australia.

Another study found that more selfie-viewing was associated with negative self-esteem. Yet another revealed a link between photo-editing and acceptance of cosmetic surgery. “It makes sense that platforms where enhancements are so easy could make you more interested in enhancements that are permanent,” Engeln says.

2-D Changes in a 3-D World

Michael Reilly, a cosmetic and reconstructive surgeon at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, has observed shifts in his practice. Whereas past clients were often concerned about flattening the bump on the ridge of their nose, current clients focus on symmetry and making the nose smaller, Reilly says. Patients also ask for wider eyes, a more angular chin, and even skin tone. Vashi has noted the same trends, which are likely rooted in the shift to selfies.

The countless tiny tweaks possible on editing apps are difficult to replicate in practice. Plumping lips, arching eyebrows, widening eyes, whitening teeth, and evening skin tone—they create a completely different face. “When people take their image and, for lack of a better word, ‘zhuzh it up,’ those often aren’t things I can do surgically,” Reilly says.

Changes driven by 2-D photos can also be at odds with the 3-D world. Current clients tend to want an extremely small nose—but that desire may be driven by the distortions inherent in taking a selfie. “The nose is an obvious point of concern for people. They’re like, ‘Oh my god, that looks big!’ Well, you’re holding the camera 18 inches from your face and taking the photo with a fisheye lens. Yeah, your nose is going to look big,” Reilly says.

A Stanford computer scientist teamed up with plastic surgeons at Rutgers to actually quantify that difference. Selfies taken a foot away increase the perceived size of the nose by about 30 percent, they report in JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery. Says Reilly: “You can make yourself look better in a selfie and then the real thing is like ‘whoa, what happened?’”

For both clients and cosmetic surgeons, it’s crucial to understand how enhancements influence impressions in real life, not just on social media, Reilly says. His research shows that procedures have the potential to change how personality is perceived. “Life isn’t 2-D,” Reilly says. “Not everyone cares whether you look younger. They care about if they want to engage with you. Do you look like someone they’d want to work with? To be their child’s teacher? These things are more about the human experience and less about internal self-esteem issues.”

Warped Perception

For many, cosmetic surgery can be incredibly empowering. Altering a single feature that has perpetually plagued one’s self-esteem can relieve insecurity and instill confidence that benefits careers, friendships, and romantic relationships. But photo-editing may exacerbate disordered body image in vulnerable individuals.

People with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) are preoccupied with an imagined or real physical flaw that an observer might not even notice. They constantly monitor and try to fix or hide the perceived flaw. They may check the mirror or seek reassurance dozens of times a day, says Hilary Weingarden, a body dysmorphia expert at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Does photo-editing cause BDD? “I don’t think we know that,” Weingarden says. Certain personality traits, such as rejection sensitivity and perfectionism, as well as genetic factors, may contribute to the development of the disorder—and exposure to images filtered to perfection. “A lot of factors are working together, but social media may play a role in making people more vulnerable,” Weingarden believes.

People with BDD represent 2.4 percent of the population but 13 percent of cosmetic surgery patients. And they may not be the right patients for a procedure. “Because BDD is a body image disorder, cosmetic treatments aren’t very likely to fix the problem,” Weingarden says.

Patients often take a few different paths, she explains. They may find a new troubling feature to fixate on, sparking a cycle of fixation and surgery. They may feel more distressed, because the change failed to deliver the expected infusion of self-esteem. They may feel at fault, because they’ve now made a conscious choice in designing the face they so detest. Eighty-one percent of people with BDD who get cosmetic treatments are either “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with the outcome.

Weingarden encourages cosmetic surgeons to familiarize themselves with the diagnostic criteria of BDD and administer the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire to patients in the waiting room. If the patient scores high on the questionnaire, surgeons could consider psychological or psychiatric treatments as a path forward.

Maya doesn’t edit her photos anymore. But she admits that she still scrutinizes others’ photos and compares herself to them. She’s more aware of all of the behind-the-scenes procedures, which makes her feel frustrated and angry. Her solution has been to unfollow her stable of influencers and spend less time on the platform. “Being on Instagram 24/7 wasn’t good for me. So I stopped feeding my obsession,” she says. “But I still go for fillers.”

How to Bolster Your Body Image

- Educate yourself about unrealistic beauty ideals. Remember the many steps taken to create the beautiful images you see every day.

- Retrain how you look at yourself in the mirror. Those with BDD zoom in on one feature, which can further warp their perception. “Imagine if you stared at your fingers up close for five minutes. They’d probably start to look distorted,” Weingarden says. Stand a reasonable distance from the mirror, allocate attention across your whole body, and note the features you like, too. Try to observe your reflection objectively and avoid harsh or judgmental words like “disgusting.”

- Deploy cognitive behavioral skills, such as identifying unhelpful thought patterns. One such pattern that pertains to body image is all-or-nothing thinking. People may believe they look either perfect or terrible. Challenge those extremes. Another technique is to ask, “what would I say to a friend?”

- Take time away from social media. If an indefinite break feels daunting, avoid social media for 48 hours. Acknowledge that it’s hard to stay away, because the platforms are designed to sustain attention. Then track the role they play in your life: What do you try to achieve through social media? To feel beautiful or sexy? To connect with friends? Reflect on whether the platforms truly provide that validation or connection. Cognitive resources are finite, Engeln says. By logging off, we offer ourselves the opportunity to devote mental energy to what we find most meaningful.

*Maya's name has been changed to respect her privacy.

Facebook image: IVASHstudio/Shutterstock