False Portraits

Discovering that you are a certain “type” can be fun, thrilling, reassuring—and seriously misleading. Why do popular personality tests still draw us in?

By Jennifer V. Fayard Ph.D. published December 20, 2019 - last reviewed on January 23, 2020

As a freshman in college, I made the perplexing observation that some of my friends back home seemed to change into different people once they went away to school. I started to crave insight into why we do what we do and how we become who we become. One autumn morning during my first semester, in 2002, I arrived to class to see that the professor had invited a special guest that day—a testing company representative who would be administering the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) to the class. The professor said that it would measure our personalities. I was fascinated. The Myers-Briggs seemed to be a gateway to answering my every question about human nature. I was genuinely proud that my type—INTJ, for introverted, intuitive, thinking, and judging—supposedly represented only 1 to 2 percent of the population, and I sat at the computer in my dorm room researching it late into the night. I began to use my type to explain to myself and others why I did a particular thing or thought a particular way. Everything suddenly seemed to make sense—I had a language to describe differences between people. This experience helped spark my interest in personality, which ultimately led me to become a personality psychologist.

In graduate school, however, I learned much more about how scales are constructed and how we determine whether they are actually measuring what they claim to measure. To my chagrin, I also quickly found out that personality psychologists generally do not use the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.

Should you? I’ll be the first to admit that tests like the MBTI are fun. But if you truly want to learn about yourself or use the results to make real-life decisions, you should be aware of the red flags that scientists have raised about tests like these. Some approaches to analyzing personality rest on less solid foundations than do others, even if people find in them compelling—even convincing—images of themselves.

Signs of Trouble

Developed in the 1940s and loosely based on psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s personality typology, the Myers-Briggs (along with its knockoffs) has been taken by millions. Upon completing the test, one receives a four-letter personality type based on one’s supposed preferences for navigating the world: These include either an E for extraversion or I for introversion; an N for intuition or S for sensing; a T for thinking or F for feeling; and a J for judging or P for perceiving. These combinations result in 16 possible personality types, such as INTJ or ESFP.

Those who have not taken this test already have likely seen one of its many viral mutations on social media. According to the Harry Potter Myers-Briggs chart, I’m Draco Malfoy. There are also charts that connect types with characters from Star Wars, Disney films, and other pop-culture favorites. The official MBTI is ubiquitous in the corporate world: Managers use the test for hiring, promotion, and team-building workshops. Outside of the workplace, people share and bond over their results, listicles tout the ideal date or most fitting city for particular MBTI types, and companies use them to market products and services.

Another test, the Enneagram personality system, is also popular online. The Enneagram, which includes mystical elements and purportedly has ancient origins, groups participants into nine types based on the numerals 1–9, with a secondary type, or “wing,” represented by a different number.

It’s hard to swing a proverbial cat online and not hit a reference to one of these tests. So what’s the problem?

Jung developed his theory of personality based on personal insights. Modern research on personality, however, contradicts the idea that individuals tend to fall into distinct categories such as “thinkers” or “feelers,” “sensates” or “intuitionists,” and “judgers” or “perceivers.”

Consider the MBTI’s scoring format, which places individuals into one of each pair of categories regardless of how extreme their scores are. A person who scores a 53 percent on the introversion-extraversion dimension receives the same result as someone who scores 95 percent: Both are labelled “extravert.” The person who scores 53 percent, however, is probably much more similar to the “introvert” who scored just below the 50 percent mark. Personality “types,” therefore, miss a lot of information; by characterizing everyone as either an introvert or an extravert, we gloss over the reality that most people actually land somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. Forced choice fails to capture the dimensional nature of personality.

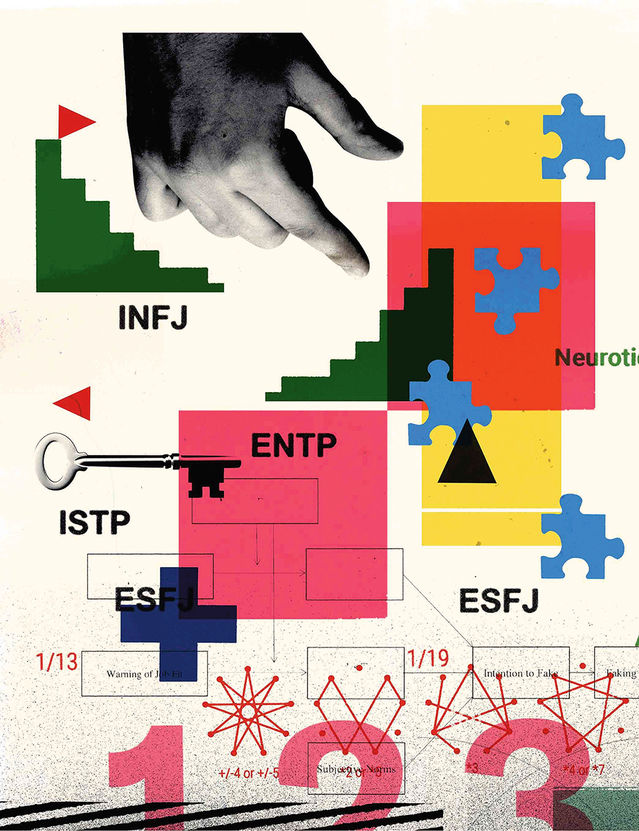

The MBTI’s types in any one individual are often not consistent over time: You may well take the test on multiple occasions and receive different personality types, even if you have not changed drastically in real life. Research has found that over a period of only a few weeks, up to half of participants received two different type scores. Developers of the MBTI even acknowledged that in their sample, 35 percent received a different type after a four-week period. And despite the use of the MBTI in work settings, research does not suggest that the MBTI types are especially good predictors of job outcomes.

The Enneagram is similar in many ways to the MBTI. Its types have some overlapping content, and two or more of the types may seem to fit the same person equally well. When a friend of mine who is very interested in the Enneagram begged me to tell him which type I was, I found that none of them described me terribly well, but types 1, 3, and 5 were the closest—and each contained characteristics that I identified with to the same degree.

Classify Me

My goal is not to host a personality test trash-fest, but rather to ask another question that, to me, is more interesting: If these tests don’t work as well as many people think they do, why do they remain so popular, and why do some people take their results so deeply to heart? Why did I? Here are some potential answers.

1. We seek hidden information about ourselves.

People crave self-knowledge. In an episode of the podcast The Black Goat, personality psychologist Simine Vazire suggested that we like personality tests because we hope that they will reveal previously hidden information about ourselves. Many believe that we have a “true self” buried underneath what we see on the surface. Personality tests themselves can contribute to our feeling that we don’t know ourselves well or that there is something more to be revealed. Recent research suggests that when we perceive personality test questions to be relatively difficult to answer, we assume that those questions are more likely to be getting at something deep or otherwise inaccessible.

In truth, we may already know ourselves quite well. Research suggests that friends and family, and sometimes even strangers, tend to see us pretty similarly to how we see ourselves. There might be things about yourself you don’t know, of course, but to find out, you might be better off asking your best friends than taking the MBTI or Enneagram test. Research indicates that friends might be better judges than you of your creativity and intelligence—qualities that we may not be able to evaluate in ourselves objectively due to their desirability.

2. We want to belong.

Feeling understood and normal, perhaps for the first time, is a powerful experience. A friend of mine recently described her memory of taking the MBTI when she was in high school. As an artist, she felt different from her peers, and she said it was a great comfort to know that there were others out there like her. Other people, no doubt, have had a similar response, and it’s no surprise that someone would react negatively to the idea that the place where they finally fit in isn’t real.

3. We want simple ways to understand other people.

Understanding and relating to other people is hard. If it were easy, books and services about navigating relationships of all kinds wouldn’t be a lucrative industry. It is tempting to wish for a simple shorthand that would allow us to understand people’s tendencies and motives at a glance, sparing us the hard work of trial and error and awkwardness as we get to know them.

This is just what tests like the MBTI and Enneagram purport to do. In theory, knowing someone’s MBTI type or Enneagram number enables understanding and responding in a way that allows for smooth social interactions. We naturally categorize everything we encounter, and we use those categories to help us make sense of the world around us quickly and with minimal energy. Why should people be any different?

Such motivations likely help account for the appeal of type tests. But they don’t entirely explain why people can be reluctant to acknowledge that their personality type may not truly describe them well. The presentation of test results and the way we process self-relevant information combine to create a convincing case.

If the Type Fits...

Personality tests can feel very accurate even when they are not. Perhaps you’ve met someone who claims to be an Enneagram 3, and it seems as if that description fits them to a T. One potential reason for this illusion of accuracy is confirmation bias: When we believe something is true, we begin to filter information based on that belief. When someone says that she is a 3, you may more easily notice and remember behavior that is consistent with that type and fail to notice or even actively explain away inconsistent behavior. This difference in attention may lead you to feel that her personality type is accurate—after all, you’ve seen a lot of evidence of it in her behavior.

Confirmation bias applies to thinking about our own personalities, too. When elements of our personality description don’t fit us well, we may assign less weight to those elements and more to the ones that fit (or those we want to fit).

We love when tests “get” us. The feeling of being recognized may relate to the way we process self-related information. In 1948, Bertram Forer conducted an experiment in which he had participants take a personality test and then gave them what they were told were their personalized results. But he actually gave the same description to all of them. It consisted of several general statements that could apply to almost anyone, such as “You have a great need for other people to like and admire you” and “You have a tendency to be critical of yourself.” A majority of the participants believed the generic feedback was very accurate, providing evidence of what came to be known as the Forer (or Barnum) Effect.

Many of the personality profiles associated with MBTI and Enneagram types are quite general. For example, in the official description of the MBTI types, you will find statements that could apply to nearly anyone:

- “[They] like to have their own space and to work within their own time frame” (ISFP)

- “Want an external life that is congruent with their values” (INFP)

- “Enjoy material comforts and style” (ESTP)

- “Want to be appreciated for who they are and for what they contribute” (ESFJ)

Research also suggests that in personality descriptions that contain both positive and negative attributes, we tend to rate the positive qualities as more accurate than the negative ones.

Consider the names of the Enneagram types: The Reformer (1), The Helper (2), The Achiever (3), The Individualist (4), The Investigator (5), The Loyalist (6), The Enthusiast (7), The Challenger (8), and The Peacemaker (9)—all good things to be. The MBTI types do not officially have names, although some sites have created more descriptive labels. During my extensive search for information about my supposed type, INTJ, I found a description that called it “The Mastermind.” I’ll take it!

To its credit, the Enneagram does admit that we can have negative tendencies. However, the MBTI descriptions are all positive. This is one way we can be sure the types aren’t completely accurate—even the most admirable among us have faults.

A Better Way to Slice Personality

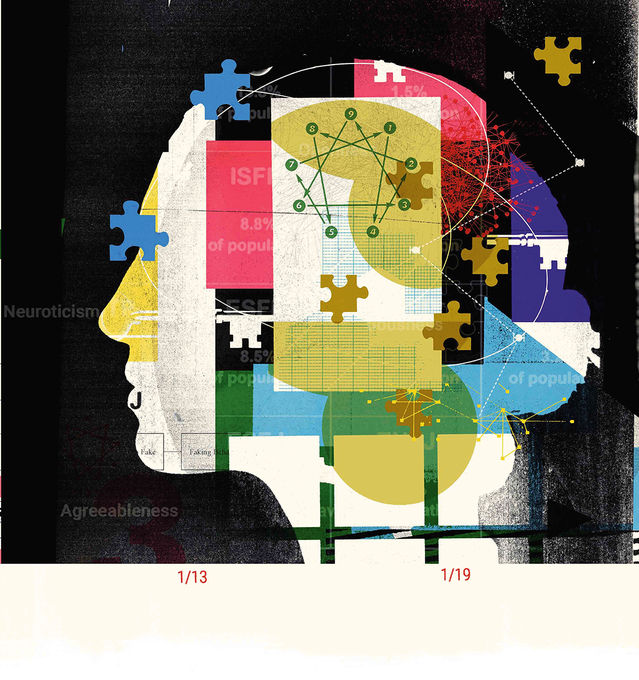

Most personality psychologists use tests that measure the Big Five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience. These five traits represent five categories of individual characteristics that tend to cluster together in people.

You’re probably familiar with the term extraversion, and its reverse, introversion. Many people think of extraversion solely as one’s level of sociability. Sociability is one part of extraversion, but the trait actually encompasses much more: assertiveness, activity level, cheerfulness, excitement-seeking—all characteristics that tend to be strongly correlated with each other. (The MBTI assesses a slightly different version of extraversion, and any negative implications of low extraversion—such as perceived aloofness—are absent.)

Agreeableness refers to a person’s tendency to be trusting, kind, cooperative, sympathetic, humble, and generous. Conscientious people are persistent, hard-working, self-controlled, responsible, and organized. Emotionally stable individuals worry little, are not moody or self-conscious, and have low levels of anxiety, depression, and hostility. Some Big Five surveys use the term neuroticism, the reverse of emotional stability. Finally, people who are high in openness to experience enjoy trying new things, have a variety of interests, and are intellectual and imaginative.

Although scores on the MBTI dimensions are correlated with Big Five scores, most are correlated with more than one of the Big Five traits, meaning that each MBTI dimension may represent a blend of several traits. Importantly, emotional stability is not a component of the MBTI.

The Big Five traits describe consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. If you sometimes seem a little different in certain situations or with certain people, this may be because some situations require us to behave in ways that are contrary to our natural tendencies.

In addition to the main traits, many Big Five questionnaires also measure each trait’s facets, or subcomponents. For example, a scale that measures extraversion at the facet level might give you a score on sociability, assertiveness, activity, cheerfulness, and excitement-seeking. This allows for a more personalized, nuanced measurement. If you are moderately extraverted overall, it may be because you are somewhere in the middle on each of its facets. However, it might mean that you are high on some facets and low on others.

The Big Five are largely independent of one another, which means that your score on one trait does not determine your level of another trait. Being reserved (an aspect of low extraversion) does not mean that someone must also be self-conscious (low emotional stability). Similarly, being achievement-oriented and self-disciplined (high conscientiousness) does not mean by default that you are intellectually curious (high openness to experience), although you may be.

Here’s why the Big Five tests win handily over the MBTI or Enneagram:

1. They were developed using the scientific method.

In contrast to the MBTI and Enneagram, the Big Five and its underlying theories were developed through careful, scientific observation. Some of the earliest studies investigated the lexical hypothesis: If there are characteristics on which people differ, and if understanding those differences is important for understanding and interacting with people, any culture will have created a word in its language to describe each of those characteristics. There are about 4,500 words in the English dictionary that describe personality traits. Through analyzing people’s ratings of themselves and others on those traits using a statistical technique called factor analysis, which groups characteristics by how strongly they’re related, researchers found five major clusters of characteristics.

2. Continuums are better than categories.

The MBTI and Enneagram give you a personality type—a discrete category that is qualitatively different from other categories. But the Big Five traits are measured on a continuum from low to high.

Psychologists prefer traits to types. One reason is that types are a collection of multiple traits. The description of the ISFJ type (introverted, sensing, feeling, and judging) includes qualities like quiet, responsible, and considerate, which represent three different dimensions of the Big Five—extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. Yet they’re all lumped together in one category. Big Five scales assess traits separately and with more nuance. Also, because types often include multiple traits, there is overlap in personality types, and people may see themselves in multiple types.

Type-based approaches categorize people as this-or-that, when in reality, human qualities are better represented by a continuum, with more of us in the middle than at the ends. This principle is reflected in the way the Big Five are measured, with questions using a sliding scale rather than a multiple-choice format.

3. They can show how you’ve changed.

If you look back at yourself 10 or 20 years ago, you will likely discern some ways that you are different now. Sometimes those changes are subtle, and sometimes they are large, but you are likely more emotionally stable, assertive, agreeable, and conscientious than you were years ago. The ability of personality types to account for such meaningful changes is dubious.

When individual traits are instead measured on a continuum, as is done in Big Five assessments, you can see whether you have changed on certain characteristics and exactly how much. If I scored a 57 (out of 100) on openness to experience as a college freshman and a 72 today, I can see that I have increased markedly in openness. My other personality traits may have changed in that time, too, in small ways or large.

4. They predict things that personality should predict.

If your personality leads you to approach the world in characteristic ways, we would expect it to be related to the choices you make and what happens in your life, right? The Big Five have been shown to predict satisfaction with life, education and academic performance, job performance and satisfaction, relationship satisfaction and divorce, physical health, how long people live, and more.

So why are most people unfamiliar with the Big Five? In a nutshell, we’ve got it, but we haven’t flaunted it. Most personality researchers are just that—researchers—and are much more interested in and skilled at scholarship than they are at marketing. As such, we haven’t done a great job of advertising our findings to the general public. Testing companies have been very successful in selling their models because they are for-profit businesses.

The Search Continues

While the Big Five are scientifically valid and capture a great deal of the human experience, they measure only what psychologist Gordon Allport called “common traits,” characteristics that you can compare across individuals. They do not account for everything that makes us unique—our tendency to stop and move turtles out of the road, our particular brand of wit, our love of all things autumn, or other quirks. But no test can do so. Nor do the Big Five capture motivations, emotions, values, beliefs, talents, and “dark” traits such as psychopathy and narcissism, although personality psychologists study these variables, too.

Finally, most of the work on the Big Five has been done using Western samples. The evidence that the same five factors work the same way in other cultures is mixed, and it’s one of the big questions we’re currently tackling.

While the Big Five system may not reveal any hidden secrets about you, it can help you summarize what you perceive about yourself. Like the MBTI once did for me, it can give you a language to talk about who you are—and what makes you similar to and distinct from the complicated people around you.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.