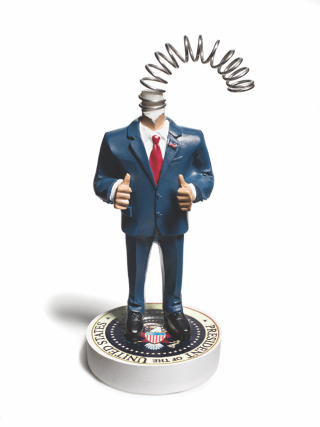

A Handle on the Head of State

The U.S. presidency is a cognitively demanding job, yet there is no requirement for assessing a president’s mental fitness to govern. At what point does the clinical become the constitutional?

By Hara Estroff Marano published January 9, 2018 - last reviewed on June 13, 2023

When the history books are eventually written, George W. Bush may be revealed as one of the more psychologically enlightened of presidents. Not once but twice during his eight years in office, he voluntarily submitted to neuropsychological testing to confirm his cognitive fitness to resume the powers and duties of high office after undergoing anesthesia for a minor medical procedure.

Had Ronald Reagan allowed even informal mental evaluation, he might have been spared the ignominy of the Iran-Contra scandal. Not only would his tenure be untarnished, and six of his aides unindicted, the course of affairs in the Middle East might arguably be different today. Although Reagan authorized the clandestine arms-for-hostages deal while hospitalized in July 1985, he later claimed he had no recollection of doing so. And maybe he didn’t. Even his White House physician, who was never summoned to the secret bedside signing, doubted that the 74-year-old president had the capacity to understand what he was approving at the time, a few highly medicated days and sleepless nights after extensive surgery for what proved to be a cancerous colon.

Two hundred and forty-two years into the republic, 73 years into the nuclear age, and a year into the 45th presidency, the mental state of the most powerful person in the world is not confined to discussions of postsurgical proceedings. It’s a topic of everyday concern in just about every medium in every corner of the globe. Given his often incendiary actions and agitated tweets, it dominates news reports and editorials, launches public discussions, and is the sole subject of at least one bestselling book, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 27 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President, edited by Bandy Lee, a forensic psychiatrist on the faculty of Yale Medical School.

Neurologists and psychiatrists pinpoint several aspects of cognitive status that bear scrutiny in any president. First, and perhaps foremost, is general intellectual ability and mental processing skills. Then there are questions of impairment due to chronic processes of neurological deterioration, such as dementia, although acute infections are also known to undermine cognitive clarity. In addition, use of alcohol and/or drugs (prescribed or otherwise) could degrade mental function, as could any kind of head trauma, present or past. Psychiatrists particularly focus on personality, mood, thought, and behavior disorders that can disrupt attention, perception, memory, or any pathway of mental processing.

At some point, the cognitive competency of the commander in chief is a matter of constitutional as well as medical concern. Whether the current head of state is skidding through cognitive decline or has a diagnosable personality or character disorder that alters mental processing may never be known. At the very least, his behavior has alarmed many. It has also incited a few to take steps to ensure that there’s a mechanism for determining mental fitness. As inadvertent a consequence as this is of Donald Trump’s ascendance—unwitting in every sense of the word—it may prove to be Trump’s towering achievement: It would fulfill the intention of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution.

Prompted by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, proposed by Senator Birch Bayh in 1965, and ratified in 1967, the 25th Amendment establishes protocols for the transfer of power in the event a president can’t carry out the duties and powers of office. Of the four sections to the amendment, the first two establish orderly succession to the presidency and vice presidency in the event of death, resignation, or removal from office.

Section 3 confronts incapacity. It allows a president, by written statement, to transfer power voluntarily to the vice president temporarily—such as when about to be disabled by anesthesia before surgery—and resume office upon recovery. It’s been invoked three times—first by Reagan before undergoing his colon cancer surgery in July 1985, although all evidence indicates he reclaimed his powers prematurely, and twice by George W. Bush, who took the extra step of submitting to objective measures of mental readiness before resuming office. At such times, the vice president becomes acting president; there’s no power vacuum, everyone knows who’s in charge, and the government operates without a hitch.

When a president becomes impaired but is unable—or unwilling—to recognize the incapacity, Section 4 could be invoked. It allows the vice president and a majority of the cabinet to determine that the vice president should carry out the duties of the presidency until the president regains the ability. It also allows for the vice president and a “body” set up by Congress to make the determination: The amendment’s framers were aware that a president could always dismiss a cabinet member—or all of them. How extreme does a mental impairment have to be for the president’s hand-picked men and women to risk their own privileged positions in order to remove their leader?

Section 4 has never been put to use. “That’s the tough one,” says Robert Gilbert, emeritus professor of political science at Northeastern University. “Involuntary transfer of power. It puts the vice president in a very awkward position: A president who’s conscious could see it as an attempt at overthrow and could retaliate by eventually forcing the vice president off the party ticket. To announce that the president is psychologically unfit could also be devastating to a president’s reputation” and undermine national security. Not least, it raises uncomfortable questions of medical confidentiality. And exactly what constitutes impairment and how is it determined?

Nevertheless, many legal experts, political scholars, and mental-health experts contend that the nature of world events today demands that the Oval Office be occupied by someone instantly able to muster good judgment. At the same time, the advancing age of presidential contenders amplifies executive vulnerability. Despite the 25th Amendment, the very lack of guidelines and procedures to evaluate whether a president is fit to serve may be imperiling national security.

Jimmy Carter certainly thought so. In 1994, Ronald Reagan revealed that he was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, sadly confirming what many had suspected, especially during his second term in the White House. Carter, his presidential predecessor, was stirred to action by the Reagan revelation. He convened a Working Group on Presidential Disability to come up with a way to carry out the aims of the 25th Amendment. It was coheaded by a neurologist, James Toole, of the Bowman Gray School of Medicine in North Carolina, and a historian, Arthur Link, whose studies of Woodrow Wilson—incapacitated by a series of strokes while in office—made him an authority on presidential impairment.

The group, which also included former White House physicians and constitutional scholars, agreed that the best way to determine fitness for office was through everyday observation as well as neuropsychological tests. Accordingly, it recommended that presidents appoint a senior White House physician to be given high rank and special responsibility to the 25th Amendment.

But a president’s physician has potentially conflicting responsibilities—maintaining patient confidentiality, on the one hand, and informing others in government and the public, on the other. The group disagreed sharply over how to handle the pressure such an individual might be under to conceal information about impairment. The Working Group report recommended that the senior physician be empowered to call on outside consultants as needed. Dissenters instead recommended establishment of a standing panel of medical consultants; a panel, they said, would provide a better buffer against cover-ups and be less subject to partisan bias to boot.

Significantly, the group took pains to distinguish political and medical responsibilities, tacit acknowledgment that drawing a line between the two is likely to be particularly challenging in practice. “Determination of presidential impairment is a medical judgment based on evaluation and tests,” said the group, recommending a strictly advisory capacity for doctors. But “the determination of presidential disability is a political judgment to be made by constitutional officials,” applying all the medical information about impairment to the question of whether it affects the ability of the president to carry out the duties and powers of office. In other words, this is complicated terrain—as is just about anything regarding the brain’s operation, most of the understanding of which has been gained since the Constitution was written, however prescient it was.

Nothing ever came of the Carter group proposals, published in 1997, and mental impairment of a president remained an abstract possibility—until events of the last year triggered interest in operationalizing the 25th Amendment. The question of presidential fitness took on urgency for freshman Congressman Jamin Raskin the moment he was seated in the House of Representatives in 2017. “I’m a professor of constitutional law, and I know that the 25th Amendment states that either the vice president and the majority of the cabinet or the vice president and the majority of ‘such other body as Congress may by law provide’ can determine incapacity and transfer the powers of office. But when I got here, I couldn’t find where the body was. I called over to the Congressional Research Service and found that such a body had never been set up.”

Last April, to put together the process the Constitution calls for, Raskin introduced a bill (H.R. 1987) to establish an Oversight Commission on Presidential Capacity. The proposed 11-member commission merges the medical and the political, but to make it as free from partisan bias as possible, it would have two physician members—one of whom must be a psychiatrist—appointed by each of the majority and minority leaders of the Senate and the speaker and the minority leader of the House; two members who have served as president, vice president, or a high-ranking cabinet appointee; and a leader chosen by the other 10 members.

When directed by Congress, the commission would have 72 hours to conduct an examination to “determine whether the president is incapacitated, either mentally or physically.” The president could, of course, refuse—impaired people typically lack insight into their own disability—but that would be one presumably significant piece of evidence to be considered.

The bill, Raskin explains, sets a high burden of proof procedurally. “Nothing happens unless you can convince a majority of this bipartisan body composed of experts named by Democrats and Republicans in both bodies as well as the vice president of the United States. Alternatively it is the vice president and the president’s cabinet deciding together. None of this would happen cavalierly, especially with the people and the media watching carefully.”

Raskin contends that the framers of the 25th Amendment were deliberate in not establishing what mental fitness is. Like the rest of the Constitution, he says, it is written in a sufficiently flexible way that future generations could exercise their judgment. “The purpose of the 25th Amendment is to guarantee national security and the stability of the government. There are 535 members of Congress and one president. The physical and mental fitness of the president is a matter of national security.”

Raskin’s bill now has 52 cosponsors, all Democrats, but in the current polarized political context it’s not likely to gain significant traction any time soon. The legislation makes no reference to Donald Trump, but “as the president spirals downward into mental chaos,” Raskin says, “political interest grows. We are just doing our constitutional duty.” The bill, he notes, enables the key actors to operate with confidentiality and dispatch. No public debate is needed. “And the vice president’s role is what prevents the amendment from being license for a palace coup.”

Bandy Lee, a Yale-based forensic psychiatrist who has spent her career studying and treating violent offenders and preventing violence, was also stirred to action by the new president. “Politics invaded my profession,” she says. “Boasts of violence and threats of violence, encouragement of followers to beat up campaign protesters, intimations of assassination of rival Hilary Clinton, boasts of sexual assault,” she says, set off professionally informed alarms. She organized an April conference at Yale about the special responsibility of mental-health professionals to warn about the dangers, and she began assembling a collection of medical essays—The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump—that zoomed up the bestseller list in late September, until booksellers ran out of copies to sell.

Because she contends that “among the violence-prone the menace grows as pressures on them intensify,” her concerns about the president’s dangerousness expanded as investigations into possible collusion with Russia accelerated last fall and began to yield indictments. Soft-spoken and tough-minded, she mounted a one-woman campaign to prepare for a full-blown psychiatric emergency in the White House, seeking out local psychiatrists who pledged willingness to sign orders mandating a psychiatric examination. “This is everyday stuff of forensic psychiatry,” says Lee, “but the ordinary channels [of presidential medical care] may not feel comfortable [taking action].”

What began as a perceived need to prepare for a crisis posed by one mentally questionable leader has since grown into an effort to educate lawmakers and influencers about the urgency of evaluating the mental health of all presidents. Lee’s attention is currently focused on establishing a panel to assess presidential fitness, its members—neurologists and psychiatrists—selected through a nongovernmental, nonpartisan organization such as the National Academy of Medicine. The idea of some kind of standing medical commission to examine a president for continuing fitness to serve not only picks up where Jimmy Carter’s Working Group left off, it reflects best medical practices. Further, it more comfortably accommodates the constitutional specification that the ultimate decision on a president’s fitness for duty rests with the executive branch.

Lee envisions six panel members having staggered six-year terms, with every president and vice president submitting medical records or undergoing tests to establish a minimal level of fitness for duty. The panel would also decide when emergency examination is needed. “These are ordinary norms of professional practice,“ says Lee. “Fitness-for-duty evaluations are objective and reliable. It is easy for panels to reach a consensus. Consensus panels operate all the time. We don’t change the norms of practice for a president; he’s a human being.”

“We have a mechanism for dealing with psychiatric emergency in every other citizen of the United States—just not this one,” says John Gartner. He is the Baltimore-based psychologist who organized Duty to Warn, the vocal group of shrinks who believe that the mental instability of a president like Donald Trump is so publicly observable that it compels mental-health experts to educate the public as well as lawmakers about the dangers, despite professional rules against discussing the mental state of anyone they have not personally examined. At this point, Gartner says, “It’s not just a bunch of rogue partisan mental-health professionals. It’s much bigger than that.” Duty to Warn has become a political action committee and is throwing its weight behind Raskin’s bill, organizing support for it through a grassroots campaign.

Even the most optimistic projections do not envision Raskin’s bill offering a mechanism for operationalizing the 25th Amendment anytime soon. “When Raskin started working on this, it seemed to have a snowball’s chance in hell,” Gartner says. “Now it seems merely improbable.” That is, until after the 2018 elections, when 24 seats could flip the House from a Republican to a Democratic majority. The Baltimore psychologist is currently developing a social media campaign to educate the public, targeting vulnerable election districts. “Social media is the new Normandy,” he says. His strategy is to “take a page out of the Russians’ playbook, except using the truth” to warn people that their lives are at risk. “We are weaponizing the mental-health issue. We want to literally take a cattle prod to their amygdala and say, ‘If you want your children to live long enough to have children, go vote.”

“The 25th Amendment is the safety net of the American Constitution,” says John Feerick. “I hope we never have to use it.” Currently a professor at Fordham Law School, formerly its long-serving dean, Feerick was barely out of Fordham’s law school himself when he was called on to compose the amendment, thanks to a long-standing interest in presidential succession. Over the years, he has taught it, served on public and private commissions relating to it, and organized legal clinics to reflect evolving thinking on the application of it; after all, a document written nearly 250 years ago is the ongoing pillar of our government.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the amendment, Feerick, along with adjunct professor John Rogan, convened a year-long law clinic on it. After studying the succession system and interviewing experts, participants produced a 108-page document, Recommendations for Improving the Presidential Succession System, published in a recent issue of the Fordham Law Review. Notably, the group proposed that the White House add a psychiatrist to its medical unit, “given that some presidents have suffered psychological ailments.”

“The White House physician should play a central role in any determination of inability,” says Rogan—not necessarily in making the determination but in advising the people (the vice president, the cabinet, or the congressional “body”) designated by the 25th Amendment to make the decision. “They have a level of accountability,” Rogan points out. “The vice president is elected. The members of the cabinet are confirmed by the Senate. That isn’t necessarily the case with physicians.”

Neither the amendment nor the new recommendations define inability—deliberately. The legislative history of the amendment contains discussion of “physical impairments that prevented the president from declaring himself unable and psychological impairments that prevented the president from making any rational decision, particularly the decision to stand aside.” A president’s inability “to reliably communicate with the White House could qualify,” say the Recommendations. “There’s no question that changes in society have increased the need for a capable president,” Rogan says, “but ultimately, it’s up to Congress and the cabinet to determine how to apply [the amendment].”

The Fordham paper also strongly recommends that the White House physician in any administration prospectively draw up a set of circumstances that would constitute inability—”responsible and creative contingency planning.” Aside from allowing for evolving definitions of incapacity, it would take some of the uncertainty out of real crises.

Giving the vice president authority to initiate a transfer of power in certain predetermined circumstances would likely have prevented the chaos following the 1981 assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan. After the president collapsed into unconsciousness in the emergency room, explains Northeastern’s Gilbert, Secretary of State Alexander Haig called a press conference in which, “with his hands shaking, he declared, ‘Gentlemen, I am in control here.’ He was not next in line, and It looked like a coup d’état,” says Gilbert. “It ended Haig’s career.” As the Fordham document states, “Prospective declarations of inability are needed for situations where presidential action must be taken immediately, but the president is unable and the Section 4 decision-makers are not easily reachable to participate in declaring the president unable.”

Fordham is sending the report to officers of the executive branch and members of Congress, including those on the Senate Rules Committee and the House Judiciary Committee, which are responsible for matters relating to presidential succession. The aim is to correct the “remaining flaws and gaps” in the 25th Amendment. Admittedly, having to invoke Section 4 “would be a really trying experience for the country to go through,” says Rogan. Not least because “such a serious issue raised about the president’s fitness could expose the country’s vulnerability.” It would, however, also be a mark of resilience.

It took until 1967 for the Constitution to grapple with presidential ill health. How much longer will it take for it to come to grips with impaired mental health? Formal surveys and anecdotal reports indicate that the everyday actions of today’s Oval Officeholder are perceptibly raising the country’s anxiety level. No one knows how jittery Americans are willing to get before they demand a remedy. Given partisanship and medical confidentiality issues, the potential for conflicting medical and political judgments of inability, to say nothing of individual leadership and national security concerns, there may never be a perfect way to implement Section 4 of the 25th Amendment. But the time may soon come to try.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.