Sleep

Profiles in Scientific Awesomeness: Von Economo

Sometimes, real science role models are more amazing than fictional ones.

Posted July 3, 2013

As a kid, I was a dedicated fan of the movie The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension!. For those of you who didn’t grow up an uber-nerd in the 80’s, The Adventures is a joy-ride of a science fiction flick about how rock-star/neurosurgeon/physicist/test pilot/hacker/philosopher Buckaroo Banzai (yes… he was all these things), played by Peter Weller, saves the world from being invaded by an evil general from the 8th dimension who has taken over John Lithgow’s brain.

Is this an amazing movie? Yes. Should it have won an Oscar? No. Will you feel incredibly silly for watching it? Of course.

But why was this film so influential for the 8-year-old nerd who watched it repeatedly until his VHS tape broke? Because it destroyed, for me, the stereotype as to what a scientist could be like.

Let’s face it, in movies and pop culture, scientists are usually presented according to the same old drab formula: white lab coats, thick glasses, unkempt hair, myopic world view, and a nice heavy dash of social awkwardness to boot. This was particularly true in the 80’s, before the rise of "geek chic" in the late 90's.

But at the time Bucakroo was something different. He was cool. He had a lot of friends. The ladies loved him and humanity (and some interdimensional species) respected him. He drove experimental cars through solid walls, saved people from brain tumors and could fly pretty much anything made on this planet or others.

So the young me was sold on the idea that someone could be a scientist without having to be a socially awkward nerd at the same time. Doing science became just a little bit cooler.

Okay, you might be thinking, just because this fake character from an 80’s B-movie was cool doesn’t mean there’s ever been a scientist as cool as Buckaroo Banzai.

If you did think that, you’d be wrong. Let me introduce you to a scientist almost as amazing as the fictional character Buckaroo Banzai.

A Baron, A Warrior and A Scientist

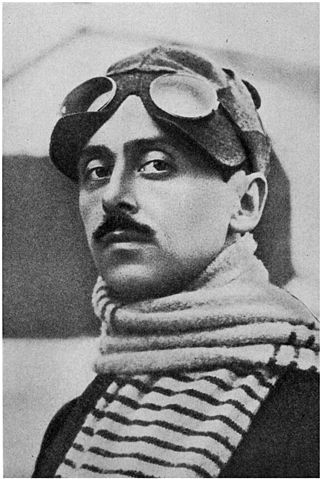

Meet the Baron Constantin von Economo.

"Back off man. I'm going to go do science while flying planes!"

Just like Buckaroo, von Economo was many things: a doctor, a fighter pilot, a philosopher, a political networker, and a scientist.

Born to Greek parents in Romania in 1876, von Economo moved to Vienna in his adulthood for schooling and quickly became a permanent fixture in Austrian high society. By all accounts he was a dashing man, with droopy eyes, a Tom Selleck moustache, a quick wit and superb conversational skills (in the five or so languages that he was fluent in). Originally trained in engineering, he eventually moved to science and medicine because he got bored with simple problems.

Von Economo was also the first certified airplane pilot in Austria and went on to fly missions for the young Austrian air force during World War I. He apparently really liked it too and would have stayed at the front lines had his family not pressured him to come back to Vienna where it was considerably safer and he could put his medical expertise to work. So he decided to come back home, marry a princess and become royalty himself… just because he could.

Seriously, he was the most interesting man in the world before that guy who drinks Dos Equis.

The REAL most interesting man in the world.

But while all these accomplishments are well and good, there was one thing that von Ecnomo was first and foremost: a scientist.

Von Economo had a deep passion for science and medicine early on. At the age of 23, he published his first scholarly work in neurophysiology. This is incredibly young for a scientist of his time and ended up putting von Economo in the close-knit circle of respected European scientists of the early twentieth centery. In fact, von Economo would go on to publish seminal works (almost 150 articles and books in total) in neuroscience and medicine, including one of the first complete cytoarchitectonic maps of the human brain that is still used today as a principle roadmap of cortical organization.

Heck, he even has a set of neurons named after him.

Von Economo’s most important contribution to science and medicine, however, happened by chance in a dreary veterans' hospital during the most dismal and fatal periods of World War I.

A Mysterious Plague

Let’s go ahead and imagine the scene.* It’s a dark and damp hospital in Vienna. Each cramped row of dust cots is filled with soldiers too wounded or sick to remain on the front lines. It is here that Dr. von Economo is making his rounds, amputating gangrene infected limbs, stitching large gashes, or treating burns.

However, some soldiers start coming back with no wounds at all. These unfortunate patients present with symptoms of a strange illness that had never been seen before. Some victims would move extremely slowly, as if stuck in slow motion. If the lights dimmed, they would fall asleep as if their wakefulness was connected to the light switch on the wall. Other patients would present with the exact opposite problems. They’d be almost incapable of sleep, suffering insomnia to the point of madness with strange bouts of uncontrollable mania and violent twitches. In some ways it looked like polio or the flu, but it was definitely not either.

Being the badass that he was, von Economo knew that this was something new and terrifying. So he decided to give it a name: encephalitis lethargica. This is the name the world would go on to call "the disease."

This new form of encephalitis would go on to become a global epidemic over the next decade. It infected tens of thousands of people, in many cases causing lethargia, catatonia and sometimes death. It was never known how it was transmitted and almost as quickly as it came, encephalitis lethargia simply vanished in the late 1920s. But during its most active periods, von Economo was tirelessly at work diagnosing, treating and trying to understanding the disease.

However, simply discovering a new neurological disease wasn’t von Economo’s greatest contribution to science. No, he was way too cool for that. It’s what he discovered when trying to understand the disease that lead to his most lasting contribution to science.

The brain’s “off” switch

The most prevailing symptom of encephalitis lethargica was disturbances of sleep. In von Economo’s time, there were two popular theories as to how the brain goes to sleep. The “Theory of Lack of Stimuli” suggested that a bottleneck of congestion in the brain blocked neural activity, resulting in the cortex going to sleep. This is pretty much how your arm falls asleep if you block blood flow to it, but applied to the brain. The second popular theory of sleep suggested that the body secretes chemicals in the bloodstream that puts the cortex to sleep. This theory was based in large part on experiments where the blood of sleep-deprived dogs was injected into healthy and well-rested animals who subsequently fell asleep.

Given his extensive knowledge of the brain, Von Economo found both of these theories to be fundamentally wrong. So he went about to prove it.

Years of post-mortem research on those who had died from encephalitis lethargica revealed severe inflammation deep in the brain, in a set of areas known as the midbrain and the diencephalon. Over time, von Economo and other scientists would match where they saw inflammation in the brain to the particular symptoms seen in the patients when they were still alive.

Those with symptoms of excessive drowsiness and catatonica also had difficulty controlling their eyes, a symptom normally seen when the optic nerve is irritated. On the other hand, patients with insomnia and twitchy movements tended to show symptoms that looked like other motor disorders that arise from damage to the basal ganglia.

From these observations, von Economo proposed that there are two distinct areas of the brain that trigger going to sleep or waking up. According to his theory, delivered in his classic lecture “Sleep as a Problem of Localization”, the neurons that promote sleep must sit frontal parts of the hypothalamus, near the optic nerve, while the neurons that initiate waking up are in the back of the hypothalamus and extend into the midbrain. So to go asleep, von Economo thought, the sleep-promoting neurons start a chain of events that quiets the cortex and, to awaken, the wakefulness-promoting neurons start an opposite chain of events.

This “on/off switch” idea of sleeping and waking turns out to be one of the most consistently validated theories of the brain to date. Modern neurophysiological studies have shown that mammalian brains do indeed have essentially “on” and “off” switches in the areas that von Economo predicted. While we know a lot more about the mechanisms of how this works, thanks to more modern scientific tools, the essential idea proposed by von Economo in 1930 still holds to this day.

Talk about a legacy!

Much like the fictional Buckaroo Banzai, the very real Baron Constantin von Economo proves that scientific role models don’t have to be socially awkward nerds who live every waking moment in the lab. They can be exciting and charismatic individuals, who fly fighter planes, try to save the world from horrifying epidemics, marry full blooded princesses, and produce elegant theories of the brain that influence science for almost a century.

Popular culture should take note, so that more budding 8-year-old scientists can strive to be as amazing as the Baron Constantin von Economo.

* Of course, I know nothing of what the hospital was like. We’ll just call it “dramatic license”.

For further reading about Von Economo's life and work, check out the lovely biography by his wife Karoline von Economo (nee Schönburg-Hartenstein) and J. Von Wagner-Jauregg. “Baron Constantin Von Economo: His Life and Work”, Kessinger Publishing, 2011 (ISBN 1169959725, 9781169959729)