Ethics and Morality

Why We Aren't Simply "Free to be Me"

And why that's a good thing.

Posted December 28, 2016

One of the great pillars of the American psyche – at least in recent generations – is that idea that we should be “free to be me”. We believe in the right for individuals to make personal choices about their lives. We believe that individuals should be, well, individuals – and not simply conform to the authority and standards of others.

Many of us – myself included – would argue that these are good things. So what’s the problem?

The "freedom to be me" is a political concept. Politically, I may be "free to be me". But that doesn't mean that the "me" that I'm free to be is good one. Not all ways of being in the world are equal. Although we may value diversity and individuality, we have to be careful not to fall into the trap of thinking that all ways of being a self are equal. We may be free to be ourselves, but not all ways of being a self are good.

Selves Are Defined Relative to Social Values

In modern times, we suffer from the misbelief that it is possible to define ourselves independent of some framework of values. We tend to think that who we are as a person is separate from how we are evaluated (by both others and by ourselves). That is, we tend to separate the “facts” of who we are from the “values” that people (including ourselves) use to judge us.

But this is not so. Humans are social beings who become themselves only by virtue of being active participants in a culture. We are not merely natural beings – we are socio-moral and normative beings. That is, we are always acting with reference to some set of standards – however tacit or implicit – of what is good or bad, right or wrong, worth or unworthy.

If this is so, we have to be very careful about what we mean when we say that we are “free to be me”. If we are (or should be) always acting with an eye toward what is good, right or worthy, then it follows that our freedom to act is (or should be) constrained by our conceptions of the good. And we are not free to define what is good, right or worthy in just any way we choose.

Our sense of what is good does not simply spring forward from within. It arises through our relationships and conflicts with others; through our appropriation or rejection of social and cultural norms; from our spontaneous feelings of empathy and care for others; from the experiences that life inflicts upon us against our wills; from our reflections on those experiences, and so forth.

Take the notion of conscience, for example. I see a person struggling to fix a flat tire. If I choose to pass him by without helping, I feel guilty. To act on my conscience – on the basis of my sense of what is good, right or worthy -- I would stop and help. In this way, my conscience guides, orients and directs what I do. But even though my conscience is “mine”, it is not something I willed into existence. Once my conscience has developed over time, the goodness, rightness of worthiness of the act of helping imposes itself on me. It is not something I simply “choose for myself”.

And so, a person is not a value-neutral kind being. Persons are not inert things with static characteristics. Instead, they are active beings who become themselves over time as they identify with some system of social values. Think of someone about whom you might say, “That person has no self”. What would that mean? It would mean that the person changes who he or she is as the context changes. Such a person would not stand for anything. Such a person could not be seen as an active agent, because he or she has no principles on which to act.

The Decline of Virtue and the Ascendancy of Me-ism

It is important to note that the very notion that we are “free to be me” is itself a social value – one that has its own social and cultural history. In fact, it has its origins in social changes that occurred over the course of the 20th century. The concept surged during the latter half of that century, when people (appropriately) began to lose faith in government, religion, established social roles, civic virtue, community standards and other shared forms of traditional authority.

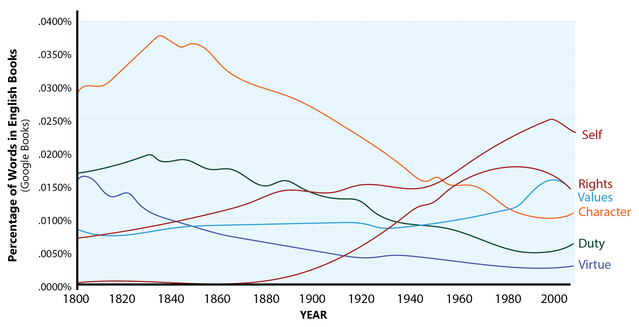

This is shown in the Google Ngram that appears on this page:

The Ngram shows the relative frequency with which a series of morally relevant terms appeared in books written in the English language between 1800 and 2000. Since 1800, the frequency in which the terms “virtue”, “duty”, and “character” appeared declined steadily, whereas interest in “self” has steadily increased. Reference to the term “values” – often regarded as a less obligatory moral concept – began to occur in the late 1800s, and has risen ever since. Finally, references to “rights” remained steady between 1800 and 1960, and has risen steadily since that time. These trends show that terms indicating various forms of moral obligation declined in frequency over the course of American history, while terms reflecting self-related meanings increased.

The notion that I am “free to be me” is a relatively recent phenomenon. We have come upon it honestly. However, we should consider what we have lost on the road away from traditional forms of moral authority. While the collapse of traditional forms of morality has given us the freedom to be ourselves, the freedom it bestows is illusory. There is no exit from moral life: we cannot remove the social frameworks that structure self and social life – we can only replace them with new ones. If this is so, it is important to become aware of the value systems that define the “freedom to be me” as a moral good.

Which is better? The mere freedom to be me? Or the freedom to cultivate values to live by?

Who is the Self to Which We Should be True?

"To thine own self be true" -- indeed. But when Polonius utters these words in Shakespeare's Hamlet, he does so in the context of providing moral advice to his son (e.g., "give each man thy ear, but few thy voice", "neither a borrower nor lender be", etc.). It is through the process of identifying with some system of social values that selves are made. Against this backdrop, "to thine own self be true" suggests something very different from the contemporary and more value-neutral entreaty to "be yourself".