Ethics and Morality

Is Radical Individualism Destroying Our Moral Compass?

The dangers of retreating into our own private morality.

Posted December 11, 2016 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- People should pursue their own versions of happiness; yet, what is freely chosen is not automatically good.

- Individual rights are essential for a free society. However, they are insufficient for a free and moral society.

- A truly moral society must seek to identify, negotiate, and coordinate the values and virtues that define how people should act.

Individual rights are the bedrock of a free society. In a liberal democracy, individuals have the moral right to make their own choices free from arbitrary intrusion—subject to the constraint that they do not interfere with the same freedoms in others.

However, although rights are essential for the functioning of a free state, they are insufficient as guides to moral action. Beyond the idea that we should respect the rights of others, a rights-based morality tells us little about how we should act toward others or who we ought to be. In a liberal democracy, such questions—that is, questions about the nature of what is good, worthy, or virtuous — are properly left to the people.

At the time of the founding of the republic, Americans experienced a rich moral life. To be sure, Americans valued liberty, autonomy, and individual rights (although mostly for white, male property owners). The focus on individual liberty, however, was tempered by a commitment to other sources of moral value. These included religion, shared (and contested) conceptions of public virtue, commitments to moral character and duty, and even shared beliefs in standards of good taste.

Over time, and particularly during the second half of the 20th century, Americans and Western Europeans began to question traditional sources of authority. Large groups of people began to lose faith in public institutions such as government, religion, community values, public virtue, objectivity, shared conceptions of taste, and so forth. As a result, a morality of individual rights flourished. The focus on rights motivated a suite of social movements—civil rights, women's rights, the rights of disabled persons; gay and lesbian rights, and so forth. These are all good things.

However, something not so funny seems to have happened on the way to claiming our rights. It concerns what Jonathan Haidt has called "the great narrowing" of moral frameworks. Over our history, the range of issues that we would call "moral" has narrowed considerably. Where moral principles of liberty, rights were traditionally accompanied by the values of public virtue, character, duty, community, and care, contemporary moral discourse tends to privilege individual rights as our primary moral principle.

This great narrowing has come at a cost. As rights have been extended to increasingly diverse social groups, we have come to appreciate the diversity of ways of being that are possible in the world. As a result, it becomes increasingly difficult to identify any single system of shared values and beliefs. Under conditions of moral conflict, whose values and virtues should prevail?

Liberalism’s solution to this problem has been to call for tolerance and respect for diverging viewpoints. However, while tolerance and respect acknowledge the limits of any single claim to a moral certainty, they fail as ways of reconciling moral conflict. Tolerance does not seek to address moral conflict; it simply stipulates a need to live with it. The desire to respect difference—while born of a desire to acknowledge the dignity of others—fails to acknowledge that not all differences can be embraced. Some sources of difference can be self-abnegating. As a result, when tolerance is strained, conflict tends to produce hostility.

However, in embracing the values of tolerance and respect, people often seem to retreat into a kind of "personal morality." If we cannot agree on shared values and ways of being in the world, in a pluralistic society, who am I to say what is right? Who am I to impose my values on you?

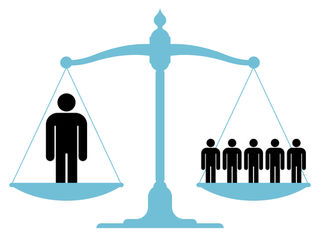

But this leads to what might be called the Great Contradiction of contemporary moral life. On the one hand, we believe in the right of people to pursue their own versions of happiness; on the other hand, the fact that something is freely chosen does not make it good, worthy, or right. If we all have the right to our own personal morality, then "the right to choose freely" easily degenerates into "If it's freely chosen, then it's all right."

Individual rights are essential for a free society. However, they are insufficient for a free and moral society. As free citizens, we need to rethink our commitment to a narrow conception of moral life. There is more to moral life than our claims to our rights. A moral society cannot sustain itself without the absence of a quest toward some shared sense of virtue, goodness, caring, and so forth. To become a truly moral society, we must seek to identify, negotiate, and coordinate the values and virtues that define how we should act, who we should be, and how we should live.

So, how can we reinvigorate virtue, values, moral goodness, and care as important principles of everyday social life? How can we invite a discussion about these issues that does not alienate people or make them feel as if they are being asked to conform to some external authority? How can we foster a conversation about the importance of moral character in everyday life? About how businesses not only have an obligation to their shareholders but also to the people whom they serve? That the values of capitalism cannot operate independently of social and moral values of care, decency, and concern for others?

References

Haidt, J., & Kesebir, S. (2010). Morality. In S. Fiske, G. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., pp. 797–832). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.