Family Dynamics

The Club Sandwich Generation

Life demands are serving up new living arrangements.

Updated February 2, 2024 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer Ph.D.

Key points

- Instability is changing the makeup of the American household; we have moved beyond the sandwich generation.

- More and more Americans are living in multigenerational, blended, co-living, and chosen families.

- Some Americans are helping relatives and peers "get back on their feet," but many are staying long-term.

- Friends and family as "social safety nets" carries benefits and strains.

When I was shifting to middle school in the 80's, my mother went back to work because my family moved into a larger home in order to make room for my grandmother to move to the United States to live with us after the passing of my grandfather. I remember hearing the term "the sandwich generation" to capture the increasing number of households where people found themselves caring for both their children and their aging parents. This was largely attributed to the baby boom and longer lifespans.

Today, a combination of factors seems to have exacerbated this issue (e.g., the "Great Recession," housing crisis, pandemic, inflation, insufficient wages, childcare, loss of social safety nets), such that it appears that a growing number of households are constituting a "club sandwich generation." Families are not only living with young children and caring for aging parents (or having aging parents care for young children), but they are also seeing adult children returning home or even taking in peers/friends, siblings, and extended family. Thus, a whole new layer to the sandwich needs to be acknowledged. We are doubling up.

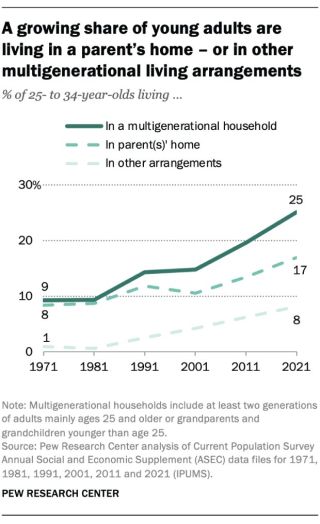

Multigenerational households are nothing new, particularly for different cultures in the United States, such as immigrants and indigenous populations, and around the world. Still, they only made up 4.7% of households in the United States in 2010; as of 2020, that number grew to 7.2%. Between 1971 and 2021, the number of people living in multigenerational households increased from 7 to 18%, despite people having fewer children. Some studies indicate even higher rates. According to Pew Research, there were approximately 60-70 million US citizens living with multiple generations in 2021. Although some might attribute this increase to the changing demographics of the nation, White Americans actually accounted for a higher share of the increase in multigenerational households since the start of the 2000's (perhaps, because they started at the lowest share).

Boomerangs

Aside from there being an increase in traditionally defined multigenerational households where there are both grandparents and young children living under one roof, we are also seeing other adults moving in. Adult children are increasingly moving back in with a parent. Called "boomerangs" — children who leave home but return — the current generation of 20-30-year-olds have a higher rate of moving back home than any other generation in the past 130 years.

This is more common among young men, where 4 in 10 American men find themselves moving back home, but young women are doing this as well. Multiple reasons, largely financial, are cited for this, such as the difficulty finding affordable housing and student loan debt. One in eight cite the pandemic as the cause. Others note delays in marriage. Sometimes these kids bring kids of their own, and you see 13% of multigenerational households having four generations under one roof.

Couch Surfers and the Hidden Homeless

Though previously conceived of as a form of cheap travel lodging, where one might go to a place and jump around between the homes of friends to avoid hotel costs, couch surfing is increasing among those who would otherwise be considered homeless, including kids. Called the "hidden homeless," these families and children are being increasingly recognized as an under-served population. Sometimes couches turn into rooms and longer stays. My sister has regularly taken in the best friends of her son. I took in a friend who was going through a trial separation and had nowhere else to go. Many of these arrangements tend to be temporary, but still somewhat long-term, and are not well-captured by household census data.

Niblings, Godchildren, and Fosters

More than a third of children live with extended family members during their lifetime, including 18% with an aunt or uncle and 24% with a relative other than their grandparents, such as godparents, adult cousins, or great uncles and aunts. For example, of the 16.8 million caregivers tending to special needs children, 45% of these caregivers are not the parents of the child. As such, if you are this extended family member — who may also already have a family of your own — you can find yourself taking in additional family members beyond your own children or parents. And for children, we see a growing trend in household transitions, particularly among those involving extended family.

A Friend in Need

Given life transitions, you might find that you have a friend who needs a chosen family. They may have had a partner deployed while they were in the last trimester of a first pregnancy, for instance. Military families often struggle with food insecurity and, as such, living with others can help prevent living below the poverty line. Another friend may have recently come out as a member of the 2SLGBTQ+ community and found themselves ostracized from their biological family. Friends may have lost a job, a home, or a partner. They may also have become disabled. 78% of disabled adults depend on family and friends as their only source of help. Although many of these problems may have been exacerbated by the pandemic, we saw similar challenges arise during other periods of instability, like the during the housing bubble burst when 1 in 5 caregivers had to move into the same house as their loved ones due to expenses. Again, these can be transitional periods of trying to help someone "get back on their feet," but not always. It captures how often family can go beyond our traditional definitions.

Co-living

The pandemic hit different people in different ways. One such way is that individuals living alone felt an extra strain of isolation during the quarantine. Indeed, loneliness in general increased during and post-pandemic, particularly among young adults and single individuals. This motivated some individuals to seek out alternative living arrangements post-pandemic. Though co-living is often seen as a new term for what may have been called communes, it doesn't require that all persons living in such an arrangement are unrelated.

All said, as economic and climate instability endure, this is likely not an exhaustive list of the different types of "doubling up" we may see in households across America. Add to these alternative households the estimated 1300 new blended families that are formed each day, and doubling up may not even capture the current family dynamics many Americans are experiencing. In many circumstances these alternative living arrangements offer many benefits, but there are also strains. There are trade-offs. These different households can pool resources and prevent slipping below the poverty line, but then there are more people to support. Neither positive nor negative consequences are well understood in current family psychology and close relationships literature, given the relative novelty of many of these new living arrangements.

What is clear, however, is that we have added new layers to the family sandwich in the 21st century. This reality is a testimony to the breadth of the term "family." In addition, this is evidence of American generosity, where home is where people will let you in even if they don't have to.