Cognition

The Origins of Words

Is it thanks to words that we have risen above the brutes?

Posted November 13, 2013

Thanks to words, we have been able to rise above the brutes.

—ALDOUS HUXLEY

Upon seeing a living chimpanzee, the bishop of Polignac in Paris in the early eighteenth century is reported to have proclaimed: “Speak and I will baptize thee.” Language is a universal part of the human condition and is widely considered to be a key to what separates us from other animals.

However, animals also have—sometimes quite sophisticated—means of communication. A bee signals the location and abundance of a food source to its hive, meerkats stand guard and alert their group about predators, birds dance with each other before selecting a mate, and in most mammals mother and offspring inform each other about their whereabouts. There are important reasons to have reliable transfer of information between members of a species, and animals have therefore evolved acoustic, haptic (touch-based), visual, and chemical ways of communicating.

Are these then not languages? Are we merely biased because we have not fully deciphered what birds, monkeys, or whales are saying? To find out what might be unique about the human communication system, we need to have a closer look at what characterizes human language. The first thing to note is that we speak not one but over 6,000 different languages. Furthermore, some people do not speak but instead use sign language to express the same wealth of information with gestures. Others can use touch to read Braille with their fingertips. Our faculty of language transcends different modalities. To examine the essential characteristics of human language, we therefore need to look deeper than the ability to utter words—which, of course, parrots share with us.

The most fundamental feature of language is that it allows us to exchange thought. In conversations we connect the private world of our minds to the minds of others. This sentence is designed to put my thinking about this subject into your head through the symbols of the written word. A symbol, be it a sound, a drawing, or a gesture, is a thing that is intended to stand for something else. Language works because individuals agree on the meaning of a set of symbols and how they should be used. Symbols are about something. That is the key to any representation: it is about something other than itself. Consider the following three paintings.

A painting by the chimpanzee Ockie

The first picture is a painting made by the chimpanzee Ockie as I sat next to him and supplied him with materials. Ockie likes smearing paint almost as much as he likes eating it. I could easily have chosen from among the paintings my daughter, Nina, made when she was a 1-year-old to make the following point: these pictures are what they appear to be—pieces of paper with paint on them. They may be beautiful, but they are not about anything else. Ockie’s painting may remind you of abstract art. Some of these pictures may, in fact, be indistinguishable from such art and are sometimes even sold as such. However, while the artist can tell you what the painting represents—even if it may sound rather absurd or far-fetched to you—as far as I know the chimpanzee paintings, like those of my daughter's, represent nothing more than themselves.

A picture of four whales by two-and-a-half-year-old Timo

The second picture is one of the first representational drawings ever produced by my son, Timo, when he was 2 and a half years old. He explained to me that it was of a group of whales. You may be able to decipher where the Papa whale and the Mama whale are; I was told that there was also a Timo whale in front of Papa and a baby whale at the top. This, then, is representational; it is symbolic. Putting aside concerns about realism, in addition to the primary reality of the color on a piece of paper, the picture represents something else, namely a family of whales.

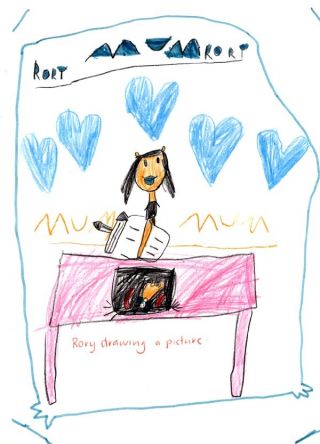

A picture by Rory (age 4) of Rory drawing a picture

The third picture is by Rory, the then 4-year-old daughter of my colleague, developmental psychologist Virginia Slaughter. It is a drawing of herself drawing a picture of what looks to be herself. This picture within a picture demonstrates an important capacity: the ability to build models of models. In this case, the drawing shows that Rory could reflect on the relation between a symbol and what it stands for. In psychological jargon, this is known as forming a “meta-representation,” and the ability to do so has many uses. It must have been essential in the evolution of any language that is comprised of arbitrary symbols. After all, to propose, understand, and agree that an arbitrary symbol has a specific meaning, people must have had an ability to reflect on the relationship between symbols and referents in the first place.

So how did we initially come up with the words to symbolize concepts in our languages? In some cases, as in the ticktock of a clock, the meaning of a word is related to its sound. This is known as “onomatopoeia.” Such words are like paintings, in that they somehow share salient characteristics of the referent. They may hence be relatively easy to agree on, and it has therefore been argued that spoken words originate from parallels between sound and meaning. However, why then are words for the same thing so different from each other in different languages? Most words do not sound anything like the thing they stand for. When it comes to abstract concepts such as “justice” or “evolution,” it is not clear how they possibly could.

Agreeing on things we can all see may be relatively easy, since you can point to an object or action and make the proposed sound or other symbol. Even if the sound is nothing like the thing in question, one can imagine that repeated pointing and co-occurrence would establish the connection between symbol and referent in a group of people. But how did our ancestors manage to establish words for concepts that are not directly observable at all?

Much of that, it turns out, has been accomplished by piggybacking on concepts that are observable. This is an important idea to grasp. We milk concrete contexts, such as what happens in a kitchen, as a source for a multitude of metaphors that allow us to talk about abstract concepts. Perhaps you need to let this idea simmer. Let it ferment. Do not regurgitate half-baked ideas. It is better to properly digest it. It is food for thought. You can cook up your own examples. But please do not stew over this for too long, even if you may have whet your appetite for more. These samples should be enough to get a taste of the nature of metaphors. They can be delectable. But they can also be less palatable, especially when they are mixed.

A long history of people employing metaphors made our languages so beautifully complex, allowing our minds to express and comprehend each other with unheralded flexibility. For the evolution of such an efficient communication system, however, we first needed to have acquired a general capacity for nested thinking (for meta-representation) as well as mental content that was worth exchanging flexibly. It is not simply words per se that allowed us to rise above the brutes, but more general capacities leading us to increasingly invent words. But I will have to save the words to elaborate on this idea for another occasion.

Copyright Thomas Suddendorf

From the book THE GAP: The Science Of What Separates Us From Other Animals