Friends

World War II Memories

Reflecting on a war I was too young to remember, I'm tempted to exaggerate

Posted May 15, 2015

I

As people reflect on the 70th anniversary of Germany's surrender to the allies, planners of a pending college reunion recently asked what I recall of the Second World War. Given my own hazy memories, I realize that soon there will be no one alive who truly remembers that distant time.

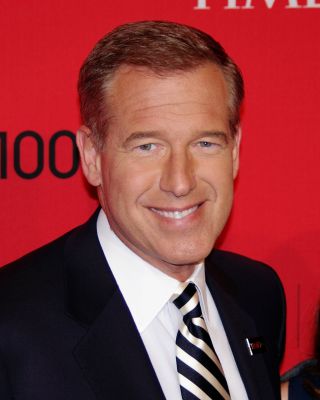

I grew up in a hi-rise overlooking Chicago’s Lake Michigan—about as cocooned from the ravages of WW2 as you could get. Nevertheless, I’ve always feasted voraciously on other people’s depictions of WW2 events. However harrowing, whether dramatized in books, films or on TV, these portrayals came to feel like part of my own psychic reality. You could say I’ve remained just one step shy of suffering a Brian Williams-type `embellishment’ syndrome—tempted to exaggerate, if not actually lie, about my own minuscule role in various WW2-related dramas, to look or feel more involved than I ever was.

My 'you were there' feelings doubtless dates to my first, vivid memory of the day America declared war on the Axis powers—less than a week before I turned 8. My parents and I were seated in our den that Sunday morning in 1941. We were listening to some music on the radio when President Roosevelt’s voice cut in. He said something about the `Japs', who'd bombed our soldiers in some place called Pearl Harbor. Then he said: `December 7. A day that will live in infamy.'

I felt I'd been struck a personal blow. “Will I still have my birthday party?” I finally asked.

“Don’t cry, Joanie, you’ll have your party,” my parents said.

Despite my fear, with a father too old to be drafted, my lack of any memory of how I celebrated turning 8, less than a week after 'Pearl Harbor,’ (as December 7th was known in the U.S. for decades), may testify to how little my life changed following our country’s formal entry into the 2nd World War.

This wasn’t true for all my grade school classmates. The lives of some of my friends, whose fathers had been drafted because they were doctors,were completely upended. They moved with their families to whatever military base their fathers had been assigned. I envied these classmates, living in new, glamorous parts of the country, with a whole new bunch of `army brats’ for friends.

I was too young to read about the war in the papers, or understand its progress through Edward R. Murrow's or the other nightly radio broadcasts to which my parents sat glued. But through The March of Time newsreels, which I watched, rivited, with my girlfriends, during my Saturday lunch and movie-going afternoons, images of the war's ups and downs seeped into my consciousness. So along with the Japs - the boogeymen of WW 2 -, Hitler and his scary-looking, goose-stepping Gestapo henchmen came to look like evil personified.

When I turned 10, and was first sent away to summer camp, I brought those haunting war images with me. Sneezing, wheezing, and huffing along on nature hikes with my bunk mates, I was too allergic to admire Wisconsin’s birch and spruce-filled woods. `Forced March!’ I would think, picturing desperate, fleeing refugees, or columns of men taken captive, trudging down endless dusty roads. 'Forced March.’

Other war memories flash through my mind: me, lying terrified in bed during those two or three nights my parents decreed—via city officials—that for security’s sake, we pull down our `black-out’ curtains. Were the Japs actually going to bomb Chicago? (Do I really remember the periodic scary shriek of an air raid siren on those nights, or am I, all these years later, confusing this sound with scenes from Mrs. Miniver or another favorite WW 2 film?) I've still no clue where we got these curtains, or what became of them after the war.

Another image: tin foil. For hours, I'd sit hunched at a table with my parents or my classmates, balling tiny leftover pieces of this pre-aluminum foil-like material. We'd been told it was vital to save these bits of foil `for the war effort.' (Leafing through some old school yearbooks, I suspect this activity was our contribution to my school’s war time 'scrap drives’.)

Rationing booklets: suddenly at home, we needed these to buy scarcities like butter, or gas for our cars. Then, just as suddenly, after V-J Day, our rationing booklets vanished.

My chief war memory: Our Victory Garden. Early in the war, my parents and some of their friends staked a claim to some `plots’ in a near-by rubble-strewn empty lot—in those days, a Chicago fixture, even in the city’s choicest neighborhoods. We grieved after the war, when we had to abandon our still flourishing Victory Garden, with its modest crops of lettuce, parsley, carrots and onions, because a new Chicago builder had seized its land. Today, in the exact spot where we dedicated Victory Gardeners once toiled, the first of that builder’s two North Side, now-landmark Mies Van Der Rohe glass and steel hi-rises looms high above Lake Michigan.

During the war I had no knowledge of, or contact with, any Jewish Holocaust victims. But at school I had several friends who knew of families who were housing one or more refugees from abroad. Friends with relatives in Europe also sometimes spoke about 'gassing' or 'the ovens.' This whispered talk was my early introduction to the real horror of what Hitler had unleashed.

Reminders of the war on Chicago's homefront at times seemed inescapable: from groups of uniformed sailors or other enlisted men or women I saw striding down the sidewalks of Michigan Avenue to the similing faces of soldiers on Uncle Sam posters or billboards. Periodic visits of an alumni/draftee to my small private school added to my perception of our fighting men as heroic, Herculean figures. I still recall the mesmerizing appearance of one such alum. Less than a dozen years older than me, this graduate clumped into our school auditorium one morning in his full paratrooper gear. He’d looked, I realized decades later, exactly like non-fighter President George W. Bush in his famous 2003 'Mission Accomplished’ speech about Iraq. (The photo of my WW2 visiting school alum, then Lieutenant John Holabird,later an architect in his family firm in Chicago, Holabird and Root, was given to me by his artist daughter in Manhattan, Jean Holabird, author of the gorgeous 9/11 book: Out of the Ruins—A New York Record: Lower Manhattan, Autumn 2001)

V-J Day remains vivid to me through such now iconic newsreel images as that of the nurse kissing the sailor in Times Square. But like the start of the war, I recall those months when the allies verged on victory in Europe in a more personal way.

I arrived home from school one afternoon in April, 1945. But when I stepped into the elevator, I saw that behind his wire glasses, our gnome-like elevator man, Walter’s pock-marked face was streaked with tears. His head began to bob up and down with each floor he passed—a habit my friends and I always laughed at behind his back. We were half way up to my 16th floor apartment, when I realized that Walter was sobbing.

“Walter, what is it?” I asked. I think he was the first adult I’d ever seen cry.

“The President,” Walter said as we reached my floor. Sobbing, he clanged open the elevator’s metal gate. “Roosevelt’s dead,” he said.

“No, you’re wrong," I said. "Roosevelt can’t be dead.”

"He is. He died at Warm Springs,” Walter said.

I dashed inside, turned on the radio, and learned that Walter was right—Roosevelt really was dead. I came back out into the hall, rang for the elevator, then rode up and down with Walter in the elevator for more than an hour, trying somehow, by my presence, to comfort him—and also myself.

Mixed with grief, I felt something like terror. Roosevelt—in office for 12 years, starting with the year I was born—was the only president I’d ever known. I doubted that either I or America would survive intact.

The world obviously did not end with Roosevelt’s death. But with the exception of President John F. Kennedy, and the early months of President Barack Obama’s administration, I’ve never viewed any other U.S. president with the trusting reverence I’d felt for Roosevelt. In recent years, however, as I’ve learned that Roosevelt’s war time policies were far from perfect, my admiration has considerably dimmed. I’m now appalled by his reluctance (to put it mildly) to help Hitler’s persecuted Jews from the time he first heard of their plight.

Nevertheless, my early belief in this strong father-figure president shaped my life-long allegiance to the Democratic Party. It was an allegiance that led me in 8th grade to cast my first vote in my school's mock election in opposition to my parents. In 1940, they abandoned Roosevelt in his 3rd presidential bid for Wendell Willkie, and permanently shifted their allegiance to the Republican party; in 1948, I proudly voted in school for the Progressive Party candidate, former Vice President Henry A. Wallace. Since then, my liberal leanings have continued to shape my preferences for my friends, and the values I later tried to instill in my own four children.

Our decision to end the war in the Pacific by dropping the two bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki also left me fervently anti-war, in addition to chronically fearful lest we or any other country, or non-state actors, will one day unleash this same, or far more unspeakably inhumane action against the world again.

I also thank WW 2 for the slow-dawning political awareness which belatedly helped turn me into The New York Times and other news-media-consuming addict I remain today. The war atrocities which I watched with such fascination in the newsreels may also have fed my interest in becoming a psychologist, and later, a journalist. In these capacities, I've often focused on such dark subjects as the insanity plea, and the courtroom jousting that sometimes made its use look as lunatic as Jeffrey Dahmer and other seemingly 'deranged' defendants who plead it. I've written also on what I've come to view as the folly of attempting to bring avowed pre-and post-9/11 terrorists to anything like `justice' in a court system which is meaningless in their belief system.

When I entered Radcliffe, six years after WW 2, I didn't fully realize what a dreadful time it was for our country. We were fighting a new, hot war in Korea. McCarthyism had brought the Cold War to new heights. Harvard had recently made its faculty sign a controversial loyalty oath, but there wasn't that much protest on campus—not for nothing were my classmates and I dubbed 'The Silent Generation'

Reflecting on my WW 2 memories, I wonder if, just as I and many of my classmates on America's shielded home front were too young to understand the true import of the war, we might also have been too young to fully grasp the horror of the post-war Red scare which was unfolding around us. In the absence of our former war-time heroes, and the nation's patriotic glow having morphed into a paranoiac minefield, it strikes me that my cohorts and I could have used some Brian Williams type braggadocio. The newscaster, who attended three colleges but was a drop-out, who has said one of his biggest regrets is not having a college degree, may—as experts speculate—have been compensating for feelings of vulnerability or inadequacy when he exaggerated his role in many of his reportorial jaunts. But sometimes bragging, or embellishing can be a good thing.

Back then, we future grads of one of the world's most prestigious universities, might have found a good role model in someone like Williams; better to puff oneself up as if trying to pass for a heroic member of 'the Greatest Generation', than to sit back like so many of us in our generation of post-war shrinking violets.