Neuroscience

The Power of One

The contributions of brain injured individuals are invaluable to neuroscience.

Posted November 18, 2013

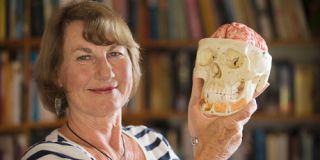

Jenni Ogden with one brain: Photo by Greg Bowker, The NZ Herald

Recently I was interviewed for a popular science series called “All In The Mind” on Radio National Australia, and the interviewer, the Executive Producer of Radio National’s Science Unit, Lynne Malcolm, titled the programme “The Power of One.” I thought this was a great title as it encapsulates my thinking on the importance of careful descriptions and assessments of single cases when it comes to understanding how the brain and mind work, and how we can best help people who have suffered brain injuries. I decided this—the power of one— would be a good topic for my Psychology Today blog but then realised that it might be even more interesting for readers if I simply copied the transcript of my conversation with Lynne Malcolm below. Then in my next blog I will expand on this topic in relation to other aspects of how the individual approach can be empowering for the person with brain injury, as well as for the researcher.

(As an aside, “The Power of One”, first published in 1992, also just happens to be the title of one of my favourite novels of all time—the novel has nothing to do with brain injury, although it is a story about a small South African boy’s dream of becoming the welterweight champion of the world—and it will be no surprise that boxing is my least favourite sport given its apparent aim of causing brain injury! But of course this novel is not really about boxing. The Australian author, Bryce Courtenay, died in late 2012; his own life which began unhappily in South Africa, is a story of the power of one. His positive philosophy about dying is worth thinking about and one that I have heard from my own patients with terminal illnesses. Here’s a link to an interview with him shortly before his death. Lynne Malcolm begins her programme “The Power Of One” with an excerpt from Jill Bolte Taylor’s TED talk; here is the link to Jill’s full TED talk. Also, if you would rather listen to the Lynne’s interview with me rather than read it below, click here for the link to the audio.

Interview Transcript

Lynne Malcolm: On RN, Lynne Malcolm with you, with All in the Mind. Today, stories of what some brave individuals teach us through their incredible personal experiences of brain injury.

Here's brain researcher Jill Bolte Taylor speaking several years ago about an insight she never expected to have.

Jill Bolte Taylor: I grew up to study the brain because I have a brother who has been diagnosed with a brain disorder, schizophrenia. So I dedicated my career to research into the severe mental illnesses, and I moved from my home state of Indiana to Boston where I was working in the lab of Dr Francine Benes, in the Harvard Department of Psychiatry.

But on the morning of December 10, 1996, I woke up to discover that I had a brain disorder of my own. A blood vessel exploded in the left half of my brain. And in the course of four hours, I watched my brain completely deteriorate in its ability to process all information. On the morning of the haemorrhage, I could not walk, talk, read, write or recall any of my life. I essentially became an infant in a woman's body.

On the morning of the stroke, I woke up to a pounding pain behind my left eye. And it was the kind of pain, caustic pain, that you get when you bite into ice cream. And it just gripped me. And I'm thinking, 'I gotta get to work. I gotta get to work. Can I drive? Can I drive?'

And in that moment my right arm went totally paralysed by my side. Then I realised, 'Oh my gosh! I'm having a stroke, I'm having a stroke!' And the next thing my brain says to me is, 'Wow! This is so cool, this is so cool! How many brain scientists have the opportunity to study their own brain from the inside out?' And then it crosses my mind: 'But I'm a very busy woman, I don't have time for a stroke!'

Lynne Malcolm: Jill Bolte Taylor from a TED talk she gave in 2008.

Jenni Ogden is a neuropsycholgist from New Zealand who's spent decades treating patients with different and often intriguing brain malfunctions. Today we'll hear about some of the amazing people she's worked with and what contribution they've made to our understanding of brain disorders. It's each person's individuality which makes them so valuable to science.

Jenni Ogden: Well, the thing about the brain is that of course it's unique, just as everyone's face has two eyes, a nose and mouth and we can recognise it, but every face is individual, and that's similar in a brain, every brain is individual. So if you have a patient who has some sort of a brain injury, it can be from a head injury or a stroke or a tumour, it doesn't matter how the brain injury happens, they will have a part of the brain damaged that probably no one else has damaged in exactly the same way. So from that, if they have some unusual behaviours or symptoms you can study those in a very careful way to show you what that piece of brain that's damaged used to be able to do. And by assessing a lot of different patients we can build up a very good picture of how the brain works or how the mind works, and relate that to the brain damage.

You can find out about how the brain works and how the mind works, both from individual case studies and also from group studies. They are equally important I think. And so group studies of course show us the big picture. For example, they've shown us that the left hemisphere in most people is dominant for language and the right hemisphere is more involved in visuospatial types of things. So there's a great many things that we need big group studies to find out the generalities of the brain, and in the individual case studies we can get more detail.

Lynne Malcolm: And so what new technologies have had the most effect on increasing our knowledge on top of that experience that you get with individual case studies?

Jenni Ogden: In recent times neuroscience is the biggest industry really in science at the moment, and so of course amazing new technologies are being developed all of the time. And some years ago now functional MRI, for example, became the flavour of the month or flavour of the year, and that is when we can see the brain in action by doing a magnetic resonance imaging scan while a person is awake in the scanner and doing some very simple cognitive task. And we can see which bits of the brain are lighting up, but that's a simplistic way of putting it.

There are many other technologies that are being developed along those same sorts of lines. But nevertheless they are still pretty simplistic when it comes to how the mind works. They are really supporting what we have learned from this rather more mundane type of study where we get a patient and we spend hours and hours assessing them carefully. But putting all that altogether, we are getting a much better idea of how the mind works and perhaps, as technology advances, we really will be able to put someone in a machine and see complex cognitive actions are going on. But I don't think we can do that yet.

Lynne Malcolm: Jenni Ogden has written about some of the patients with brain injury she has treated over many years in her recent book Trouble in Mind: Stories from a Neuropsychologist's Casebook.

So one of your patients that you write about, Luke, had Broca's aphasia, and this is affecting his language and comprehension. But he could sing his favourite blues song perfectly. Can you just describe this case and what it tells us?

Jenni Ogden: Well, he had a bleed in his brain. He was a young man, he was actually a gang member, and he had been binge drinking, and he suddenly collapsed and his gang friends brought him into hospital. And he couldn't speak. Well, he could only speak in brief staccato sorts of ways, simple words, you know, 'Me…Luke', that sort of thing. But he could comprehend reasonably well, and that's what expressive aphasia is. The haematoma, the bleed was in the left frontal part of his brain, where Broca had discovered all those years ago that it's involved in expressive language.

However, the right hemisphere we know is more involved in music, tunes, melodies, and it was discovered, probably by accident by somebody, that some of these people who can't speak normally, if they sing a song that they know that has words, the words come along as well, sort of hooked onto it. And so he could…because he knew the song 'Trouble in Mind', he could sing this and sing the words. And sometimes there is a certain sort of therapy that people do, that speech therapists do, they get the person to sing a well-known tune and then sing new words to it. You know, 'I want to go to the toilet,' for example. And so that's why Luke was able to sing 'Trouble in Mind', although he could not respond expressively in conversation.

Lynne Malcolm: So this caused you to suggest melodic intonation therapy. How did that work and how effective was it for Luke?

Jenni Ogden: That was quite effective with Luke. It's very difficult to tell with an individual case because they are not just an experimental animal, they are a real person who wants to be rehabilitated. You can't use an individual case as your experimental guinea pig for months on end. So basically you are trying to do everything to help them rehabilitate, so it's very hard to work out what has been effective and what hasn't, it's a whole mishmash of things.

But I think the melodic intonation therapy did seem to help him get some of his speech back. He also probably…as the haematoma, the blood clot resolved, the neurons weren't completely damaged, so he actually got his function back spontaneously anyway. But certainly that did help him. And it also helped him I think because it was fun. He was doing something he enjoyed. And if you are rehabilitating patients and they are constantly doing terribly difficult things that really depress them because they know they used to be able to do these things before, that's awful. So if you can have a rehabilitation program that's something that they can enjoy and that they can sometimes be successful at, that's very important I think.

Lynne Malcolm: Another case you talk about is that of Janet, and due to a tumour she began to neglect her left side. Tell us her story.

Jenni Ogden: Yes, Janet, hemineglect. That's a very interesting and bizarre disorder and is the one I've probably studied the most, I must have seen 100 people with hemineglect. So it's not rare actually, although some people think it is. What it is, it happens usually when someone has damage to the right side of their brain. It doesn't matter how the damage is caused, it could be a stroke or a tumour, and in Janet's case it just happened to be a tumour.

And she was a 50-year-old woman and she felt perfectly healthy, and she was driving home from work one night, on her 50th birthday in fact, and she banged into the left side of the garage with the car. She didn't take much notice of it, she just thought she had her mind on her birthday party. And then at her birthday she blew out the candles on her cake and she only blew out the candles on the right side of the cake and didn't bother with the candles on the left side. So people thought this is a bit strange. And she said, oh well, I don't need to blow them out. And then she had a seizure, which came from the tumour, and she was taken into hospital and they found she had this big tumour in her right hemisphere.

And then her neglect became very apparent. And what hemineglect is, is that it is when they have this damage to the right hemisphere, usually the right parietal lobe of the brain, they ignore the other half of space. And it's nothing to do with their vision or anything like that, it's to do with their higher cognitive functions. It's as if they don't want to know about that side, thank you very much. And so if they look out at a big scene, they will look out at that scene and they will sort of divide it in half and they will take notice of the right half and they will take no notice of the left half.

So if you stand on their left side they will either ignore you or they will be rude or swear at you. If you go to their right side they will be lovely. If they are drawing pictures, if they are copying a picture they will copy the right side but not the left side. If they are dressing their bodies…she would leave her dressing gown hanging off her left shoulder, sometimes quite immodestly. And then she would laugh about it. And she used to make excuses for it, because I think for people with neglect, they can't understand really why they are doing this, and so they try and make sense of it by making up some sort of story to explain it, and sometimes those stories are really bizarre.

Lynne Malcolm: And was there any rehabilitation possible in that case?

Jenni Ogden: With her, for short times there was. There are a lot of studies trying to work out how you can help these people with neglect. One of the good things about neglect is that it usually happens only briefly after the damage has occurred, and then it quite quickly spontaneously recovers, except in a small number of cases like Janet where it never recovers. And when it doesn't recover it's very difficult to rehabilitate actually.

You can help a bit by always standing on their left side and forcing them to look at you by putting jangly bracelets on their left arm so their attention is drawn to that side, and by instructing them very carefully to say…you know, they won't walk properly because they are neglecting their left leg. So you can make them say 'put my left leg down, my toe down, my heel down…' and so on. And all this helped in small ways and she understood it, but she still most of the time couldn't put it into practice for long. And then of course her tumour was a malignant tumour and it kept growing, and as it grew she would get these really bad neglect symptoms back again unfortunately. But rehabilitation can work in some cases.

Lynne Malcolm: And then there is also the condition called autotopagnosia, which is an inability to recognise or to find the parts of your own body. And Julian had that condition.

Jenni Ogden: He did. I think that's probably the rarest case I've ever come across. And yes, he was a fascinating case. He had a tumour in the other side of his brain, in the left hemisphere, exactly the opposite side in fact that Janet had her tumour. And I found, more or less by accident, that he had this very rare disorder called autotopagnosia, which means…agnosia means 'not to know', nosia means 'to know', so agnosia means 'not to know', auto means 'self', topo means, you know, topographic. But autotopagnosia means 'not to know one's own typography'. So that's the way that word comes about, that's the way a lot of these jargon-sounding neuropsychological words come about.

Anyway, so Julian had a number of symptoms, but his most interesting one was this one, where he couldn't find the parts of the human body on the body. So he had lost the map of the human body. So if I asked him to point to my left hand, he would look all over me, and he would say, 'Where's it gone? I can't find it.' And then as his eyes fell on my hand, just while he was scanning my body, 'Oh, there it is.' He knew exactly what a hand was. If I showed him a picture of a hand he said, 'That's a hand.' But he couldn't work out where it was on my body or his own body or a doll's body or a picture of a man's body.

But the fascinating thing was that if I showed him a picture of an elephant or if I gave him a toy truck, for example, and asked him to point to parts of those, he didn't have any problem, he was very quick. And what it seems to be saying was that we humans have inside our head hardwired a map of the human body. And when we are asked to point to a part of the human body we have to map it onto this image inside of our brain. And his left hemisphere damage had destroyed that.

And I think the reason we don't find many people like Julian is because most people with a tumour like his in the left hemisphere would not be able to comprehend language either, but he could. For some reason the only bits that were damaged were the bits that caused this sort of a problem, and therefore, because he was still very intelligent and expressive and could comprehend stuff, he was able to be tested and this strange autotopagnosia that he had wasn't masked by all these language problems.

Lynne Malcolm: This is All in the Mind on RN, Radio Australia and online. I'm Lynne Malcolm, and I'm speaking with neuropsychologist Jenni Ogden about how some of her brain injured patients have inspired her and contributed to our understanding of the way the human brain works.

Some people are so valuable and special that they almost become professional subjects. And as an example you cite Michael who was what you call mind-blind as the result of a motorcycle accident. Tell me about him and what studying his case actually added to your knowledge about this condition.

Jenni Ogden: Yes, Michael was another very interesting case, rare in the sense that he was a very clear, classic case of this particular disorder. And that's one of the things we neuropsychologists…it's very exciting to find. Often there will be lots of people who might have these problems, but the've got so many other problems because of their brain damage that it's very unclear. So when you find someone who is very intelligent and bright but just has specific problems, then they are very valuable as patients, though you've got to be very careful not to exploit them.

Anyway, Michael was a young man in his 20s who had a terrible motorbike accident. And he was in critical care, and he was unconscious for quite a long time. And when he came out of his concussion, it took some time before people realised that he was blind. This is amazing to me. It was actually a week before people said, oh, he's blind. He was cortically blind. He was blind because he had damage to both parts of his occipital lobes which are at the back of the brain and they are the visual parts of the brain and he had damage to both of those. And so his brain couldn't see, it's called cortically blind. So it wasn't his eyes, it was his brain.

Anyway, years later…he lived in the Institute for the Blind. Quite a long time after his damage I got a phone call from one of the therapists there, very excited, saying, 'We have this patient but he has started to be able to see again. When he is sitting in a car as a passenger he can see lights at night, and he is seeing dim shapes on the television, and it's very exciting.' So she had started to work with him, and she said he seems to be able to see shapes but not know what they are.

And so I got very involved with him and I've done many studies on him and my students studied him as well. And he had this thing called visual object agnosia, which is a well-known condition, and it means that when he is shown any object he can describe the shape of it, but he doesn't know what the shape is. And so visual object agnosia, he doesn't know what the shape is if it's visual. But if he hears it or touches it, he knows immediately what it is. So give him a key to look at, he doesn't know what it is, but if he picks it up he immediately knows it's a key, or if you jangle them he immediately knows it's a key.

So he had that problem, and he had another problem which is related in a way, and that is he had prosopagnosia, and that is not recognising familiar faces. So his mother, he could never recognise her face again, or anyone's face. If you showed him a picture of a cat's face and human's face, he couldn't tell the difference. This is a reasonably common disorder, and in fact some healthy normal people have problems recognising faces, in a much less dramatic away, and there is a lot of study being done on this. But he had a dramatic case of it. Again, not being able to put together very subtle visuospatial cues to be able to recognise a face. So he had that.

And the thing I found out that was different was that he also had lost all his memories from before the accident. He couldn't remember his 21st birthday a couple of years previously, which was a big party with lots of people and cakes and music et cetera. He had no memories, he had completely lost his memory from before his accident when he was in his 20s. And by doing a lot of studies on this I came to the conclusion it was not because he'd actually lost his memories per se, it was because of his memories when he made them in the past were very visual, and now he had no visual imagery, he couldn't make visual images in his head, he didn't dream, none of this he could do. And so because there was no visual component to them, it was as if he didn't have any memories, and that's why he had this strange memory problem, because otherwise there is no explanation because the occipital lobes are not to do with memory normally. So that's what we really learned from Michael.

Lynne Malcolm: And later in life he was helped by friends, but he was able to pursue his dream of doing a motorcycle trip on Route 66 in the United States. And his friend helped him in a really lovely way to remember the trip. Just tell us about that.

Jenni Ogden: Yes, that was wonderful, that. Michael, he is a lovely person, and one of the reasons he was so fabulous to work with is because he was so into it. If he hadn't have had these problems he would have been a neuropsychologist I think, if he'd come out of it, because he loved it, he loved all these studies and he was bright and intelligent in every other way.

Anyway, so he did do incredibly well because of this. He had to have a carer, but with his compensation money from his accident he had managed to buy his own little house and so on, and he could get around. He is like functionally blind, even though he could see, he is functionally blind because he can't recognise anything. But he would learn. And he kept his friends, which is also pretty amazing because often people with severe head injuries and don't keep their friends. After a while they get a bit tired of it all and fade away.

And one of his friends, I think it was Lou, I called him Lou (of course I changed all these people's names), and he was the head of a motorcycle gang, and of course Michael originally had his damage because of his motorcycle accident. And of course in spite of the fact he had this damage with a motorcycle accident, like all these guys he still loved motorcycles. You know, nothing is going to stop him loving these things. And Michael had always wanted to do this big motorcycle ride across America (this is an Auckland guy, you know) and do Route 66. So Lou said, 'Let's do it.'

Michael's mother was a bit concerned at first, and they said, well, why not, you know, you've got to live. So off they went, they went to America and they did Route 66, Michael sitting in the sidecar of this motorbike. And they had an accident on the way, but that didn't stop them. And when they got back of course Lou started off by making up a lovely photograph album for him to remind him. And then of course he realised, well, that's useless, Michael can't recognise the things in these photos.

So instead he made up these tapes of a whole lot of songs that reminded him of the trip. Because Michael had not lost his memory of sounds and songs. He still remembered songs from his past, so he made up these musical CDs, and he started with 'Leaving on a Jet Plane', then he included songs like 'New Orleans', and 'Needles and Pins' which is a reference to Michael's numb backside when they'd been travelling for a long time, and 'Grand Canyon'. And the CD finished with the 'Harley-Davidson Blues'. So that's what he did.

And that's the thing with rehabilitation, you get the family and friends involved, that makes all the difference. Rehabilitation is about getting as many people involved as possible and making it relevant to the person that you are rehabilitating.

Lynne Malcolm: So you established very close connections, close relationships with many of your patients with neuropsychological disorders. How has that affected you emotionally, and how do you keep the boundary that you need to keep between your patients and yourself?

Jenni Ogden: Yes, it's a very fine balance I think when you are working with people, especially over a long period. And there's one thought that therapists and doctors and so on should remain very much separated from their clients. And of course they should to a degree. But if you are a clinical psychologist and what you are doing is therapy, you are trying to build a rapport, and even if you are just assessing the person you are trying to build a rapport, because what you wants to find out in your psychology is how well they can do what they can do, not how nervous they are. You want to know how well they can do when they are feeling normal, as normal as they can be. So you need to build a really good rapport. So for research reasons it's important to have a good relationship with your patients.

And of course for human reasons that's also important. And if you are being a therapist you have to have that rapport. And you can't have a rapport, in my opinion as a therapist, without having some emotions involved in it. And I don't have a problem with therapists feeling empathy with the clients, but you do of course have to be able to also have that boundary, because you are the professional and they're the client and you've got to be careful about the hierarchy thing and the power thing in all the rest of it. And you've also got to be careful for your own health that when you go home you can in fact leave that behind.

Lynne Malcolm: What has been the most surprising and I guess heartening case of someone who has really moved through this most amazing challenge of dealing with a brain disorder?

Jenni Ogden: You know, there's so many, I find that really a hard thing to answer. In fact Trouble in Mind, I purposely chose a range of cases, but I think everyone in that book are people I have enormous respect for because I think they've dealt with whatever they've been thrown so incredibly courageously and well, even if the end was that they died. You know, they've dealt with that in an amazing way. So many, it's actually impossible for me to pick any particular one out.

Lynne Malcolm: How much hope do you hold that the knowledge that we are getting all the time is enough to improve people's lives when they are hit by some of these terrible brain disorders and injuries?

Jenni Ogden: I do, I have a lot of hope. I think there's amazing research going on all the time on how to help people cope with these things, how to rehabilitate them. And now of course we know that the brain can repair itself to some degree. We used to think it couldn't. So there are a whole lot of new things going on in that way, and of course there's a lot more technology, stem cells and all sorts of things that is changing all the time; with Parkinson's, for example. It may be that we can actually cure some of these terrible diseases. But as far as rehabilitation goes and carers and medical professionals learning how to help these people, I think there is enormous hope. It's a massive area of research, and it has come a long way in the 30 years I've been involved with it, and I'm sure it's going to continue that way.