Memory

The Story Of Memory And The Man Who Lost It

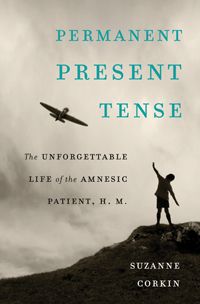

Permanent Present Tense, the biography of H.M.

Posted May 10, 2013

'Why Sir, if you have but one book with you upon a journey let it be a book of science. When you read through a book of entertainment, you know it, and it can do no more for you, but a book of science is inexhaustible'.

This quote of Samuel Johnson’s was recorded by his Scottish friend, James Boswell, in his book, Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, published in 1785, a year after Johnson’s death.

Suzanne Corkin’s new biography of Henry Molaison, the man with no memory, is a fitting example of Johnson’s wise quote. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of Amnesic Patient, H.M. (Basic Books, New York, 2013), has been eagerly anticipated since the news leaked out that Dr. Corkin had begun writing the life story of her most famous patient, H.M., shortly after his death in December, 2008. Corkin met H.M. in 1962 on his only visit to the Montreal Neurological Institute. Her supervisor, Dr. Brenda Milner, a neuropsychologist, and neurosurgeon, Dr. Wilder Penfield, both from the Montreal Neurological Institute, were the first to realize that the experimental brain operation performed by William Scoville on 27-year-old H.M. in an effort to cure his epilepsy, had rendered him amnesic. His seizures were almost vanquished, but he would never again be able to make new conscious (declarative) memories.

In 1966, at the age of 40, H.M. —as he was known until after his death—made his first of 55 visits to the Clinical Research Center at MIT in Boston, not far from where he lived in Hartford, Connecticut. Corkin was now a research scientist at MIT and “inherited” H.M., partly because of the ready access of MIT to Hartford. In Dr. Corkin’s lab, Henry was the subject of thousands of experiments on memory and other cognitive abilities. When H.M. had his surgery, it was not known that the hippocampus, the structures underlying the temporal lobes on each side of the brain, were essential for forming new long-term memories. The studies on Henry have not only taught us about memory processes and the brain substrates underlying them, but have stimulated and inspired countless students and researchers to pursue careers in neuroscience. The way in which temporal lobe epilepsy is surgically treated also changed as a result of the experimental surgery performed on H.M. In his case the hippocampus was removed from both sides of his brain; we now know that if just one hippocampus is removed, leaving a healthy structure on the other side, temporal lobe seizures can be cured without the patient becoming amnesic.

When 82-year-old Henry died in 2008, Dr. Corkin had been working with him for 46 years, yet he still didn’t know who she was. When told her name was Suzanne, he could say ‘Corkin’, but this was a superficial association of words rather than a signal that he knew her. Corkin’s book is a science book in that it tells the fascinating story of memory, and the methods, experiments and technologies developed in order to understand it; it is a history book in that it draws the reader into the lives of the neuroscience researchers, allowing us a peek into their thinking; it is a human story of the special relationship between researcher and patient; and it is a memoir about the man who did not lose his intelligence, sense of humor, or generosity when he lost his memory. For me, as one of the privileged few who worked with Henry when I was a postdoctoral fellow in Corkin’s lab, reading this book was like a walk through the past, her descriptions were so evocative, and the voices, especially Henry’s, so clear.

The last chapter, ‘Henry’s Legacy’, recounting the dramatic final journey of the most famous brain in the world, is a page turner as exciting—more exciting— than the best thriller, and takes us into the future; a future more mind-boggling than any science fiction book. After nine hours of in situ MRI brain scanning in Boston, followed by a delicate autopsy to remove the brain from the skull, followed by more scanning, Henry’s carefully protected brain had its own seat for the flight across America to the University of California, San Diego. There it was cut into 2,401 very thin slices, each one photographed. Now there is more work to do as the slices are stained and mounted on large glass slides, and the digital images used to create a 3-dimensional, stunningly detailed model of Henry’s brain that will be freely available on the internet. In the epilogue of her book, Dr. Corkin reminds us of the lovely man Henry was, as the people who cared for him and worked with him say their goodbyes, and reminisce about the good times they shared with the man who never remembered them.

For lovers of science, and those who relish a heroic story, this is a book that will stand up to a lifetime of journeys, with every reading providing inspiration and something new to contemplate.

Suzanne Corkin

Brenda Milner